Massive Star Is So Big It Gives Birth to a Tiny Twin

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

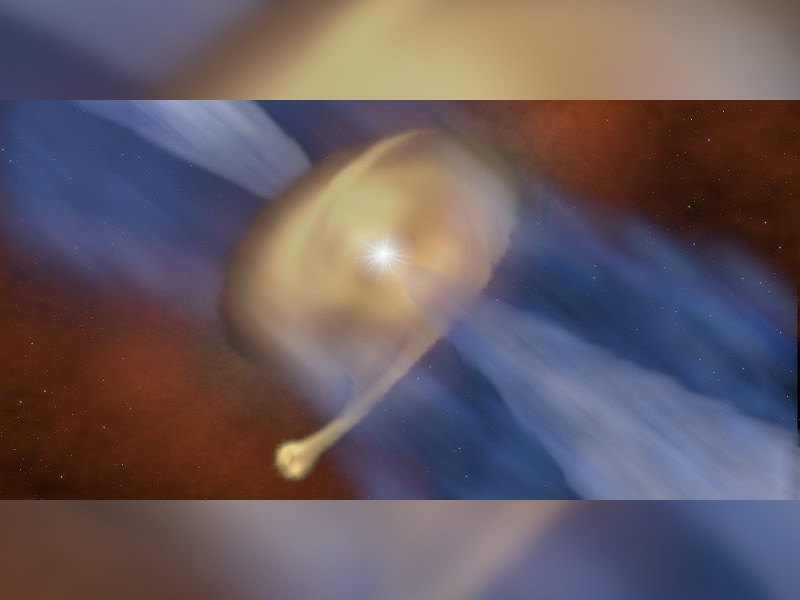

A close-up look at the birth of a star has revealed a surprise: Not one new stellar body, but two.

In 2017, scientists using a new array of radio telescopes in the Chilean desert were observing a massive young star named MM 1a in an active star-forming region of the galaxy more than 10,000 light-years away. As they analyzed the data, they realized that MM 1a was accompanied by a second, fainter object, which they dubbed MM 1b. This, they found, was the first star's smaller sibling, formed from the spray of dust and gases it holds in its gravitational pull. In a solar system like Earth's, this "disc" can coalesce into planets.

"In this case, the star and disc we have observed is so massive that, rather than witnessing a planet forming in the disc, we are seeing another star being born," astronomy research fellow John Ilee of the University of Leeds in England, who led the study, said in a statement. [6 Weird Facts About Gravity]

A mismatched pair

Ilee and his team made their observations using an array of 66 telescopes in the high-altitude Chilean desert known as the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA). By coordinating this array, scientists can detect far-flung objects as if they had an impossibly large optical telescope 2.5 miles (4 kilometers) wide.

MM 1a is huge, with 40 times the mass of the sun. Its twin, MM 1b, is a relative pipsqueak, less than half the mass of the sun. That size differential is unusual in binary stars, Ilee said.

"Many older massive stars are found with nearby companions," he said. "But binary stars are often very equal in mass, and so likely formed together as siblings. Finding a young binary system with a mass ratio of 80:1 is very unusual, and suggests an entirely different formation process for both objects."

Stars making stars

Stars condense from massive discs of dust and gases that gradually pull together their own gravity. As they coalesce, they begin to spin, and leftover dust and gas begins to orbit them.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In small stars like the sun, Ilee said, this disc of leftover dust and gas can start clumping into planets that then orbit the parent star. MM 1a's huge size, though, meant that a second star could form rather than a planet. It's one of the first times such a phenomenon has been observed, the researchers reported Dec. 14 in the journal The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

MM 1b could possibly have its own disc of space debris, which could theoretically coalesce into planets, the researchers said. But the clock is ticking for the protostar system, Ilee said. Massive stars like MM 1a last only about a million years before exploding into supernovas, he said. When that happens, the whole area will be kaput.

"While MM 1b may have the potential to form its own planetary system in the future, it won't be around for long," Ilee said.

- 9 Most Intriguing Earth-Like Planets

- 11 Fascinating Facts About Our Milky Way Galaxy

- The Biggest Unsolved Mysteries in Physics

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus