Will Climate Change Destroy New York City?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The city of New York — America's largest metropolis and home to over 8 million people — will be ravaged by the effects of climate change within a few years.

That's the bleak scenario presented by a recent 430-page report developed by a blue-ribbon panel of academics, environmental planners and government officials.

Released this month, the report, nicknamed "SIRR" for Special Initiative for Rebuilding and Resiliency, presents an ambitious plan for managing the worst effects of global warming, which include flooding, rising temperatures and extreme storms. [8 Ways Global Warming Is Already Changing the World]

The potential disasters laid out by the plan, however, could easily overwhelm New York City: Searing heat waves, pounding rainstorms and vast acreages flooded by seawater are all expected for the city and the surrounding region.

And as dire as these situations are for New York City as a whole, the implications for the city's most vulnerable populations — the elderly, children, disabled people and those with special needs — are even more ominous.

Sandy: a harbinger of storms to come

On Oct. 29, 2012, New York City and the surrounding area woke up to a reminder of nature's fury when Hurricane Sandy struck the region.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In addition to causing nearly $20 billion in damage, the storm killed 43 people and injured many more. The city's transportation facilities, including airports, commuter trains, subways and highways, were effectively shut down. [On the Ground: Hurricane Sandy in Images]

Other critical infrastructure, such as hospitals and wastewater treatment plants, were incapacitated, and millions of city residents were thrown into darkness by the flooding of electrical facilities. Communication networks were similarly crippled as personal cellphones, computer screens and other devices went dead.

Experts are quick to point out that Hurricane Sandy cannot be directly blamed on climate change, but say that similar storms are more likely in the near future, based on existing trends.

"There has been an increase in the strength of hurricanes, and in the number of intense hurricanes, in the North Atlantic since the early 1980s," Cynthia Rosenzweig, a NASA researcher and co-chair of the New York City Panel on Climate Change (NPCC), said at a recent news briefing.

And Sandy's devastation was made worse by existing climate realities. "Sea level rise already occurring in the New York City area, in part related to climate change, increased the extent and magnitude of coastal flooding during the storm," according to a 2013 NPCC document.

New York's future laid bare

After Sandy exposed New York's vulnerability to the impacts of climate change, Mayor Michael Bloomberg was emboldened to create the plan outlined in the recent SIRR report.

Among the report's many projections, written in a detached academic tone, are a number of genuinely frightening scenarios. A handful stand out as extreme events, said Rosenzweig, who refers to them as "the Big Three":

Heat waves: In decades past, New York experienced an average of 18 days a year with temperatures at or above 90 degrees Fahrenheit (32 degrees Celsius). But the city could experience 26 to 31 such days by 2020 — just seven years from now.

And by 2050, New Yorkers will swelter under as many as 57 days — almost two full months — of temperatures above 90 degrees F, the report projects. These heat waves "could cause … about 110 to 260 additional heat-related deaths per year on average in New York City," the SIRR report states.

Intense precipitation: Instead of experiencing an average of two days per year with rainfall exceeding 2 inches (5 centimeters), New York City will endure up to five such days by 2020 — almost triple the current number.

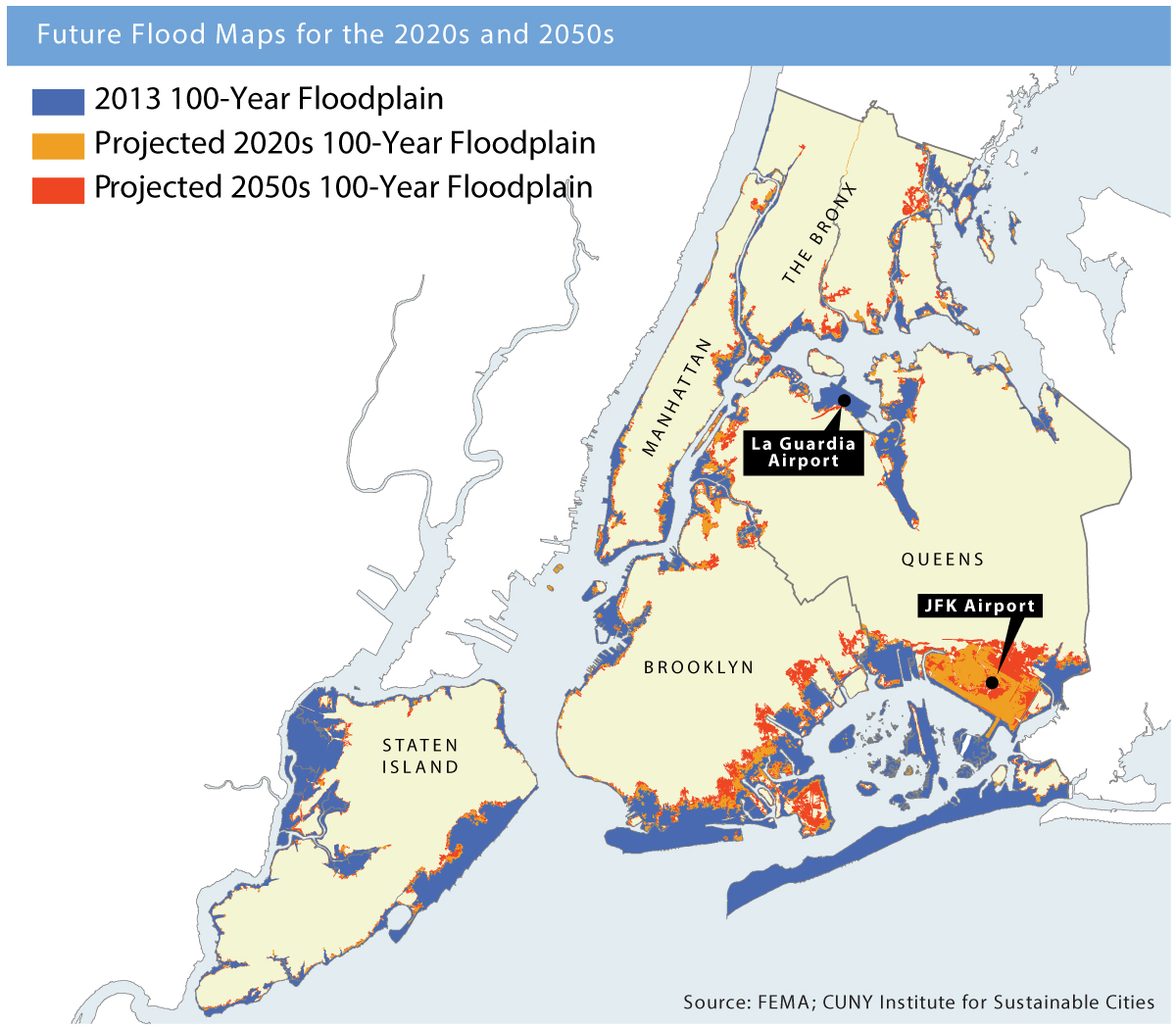

Coastal flooding: By 2020, the chances of a 100-year flood (a flood with a 1 percent chance of occurring in any given year) at the Battery in downtown Manhattan will almost double, according to SIRR projections. By 2050, the chances will increase fivefold.

The heights of 100-year floods are also expected to increase, from 15 feet (4.6 meters) to as high as 17.6 feet (5.4 m) at the Battery. These effects will be experienced dramatically in swamped coastal neighborhoods and at important low-lying facilities such as John F. Kennedy International Airport and LaGuardia Airport.

Populations at greatest risks

During Hurricane Sandy, 26 nursing homes and adult-care facilities had to be closed, forcing the evacuation of about 4,500 people. And six hospitals, including four in Manhattan, were also closed and almost 2,000 patients evacuated.

These evacuees represent just a small fraction of New York City's most vulnerable populations, who are at greatest risk from the projected impacts of climate change-related disasters, said Dr. Irwin Redlener, director of the National Center for Disaster Preparedness in New York City.

"I don't think people realize that vulnerable people — who may be vulnerable for a variety of reasons, whether they're very young or very old or sick or disabled — are roughly 40 to 50 percent of the population," Redlener told LiveScience.

"The success of disaster planning and response could be gauged by how well we handle those vulnerable populations," Redlener said. "This is a big problem, because most of our official planning organizations tend to do very generic planning."

Hurricane Sandy presented a number of case studies in disaster planning successes and failures. After Coney Island Hospital in Brooklyn lost power, backup generators supplied electricity until the generator room flooded and all power was lost.

During the height of the storm, "the staff valiantly cared for patients using flashlights and battery-powered medical equipment," the SIRR report states.

By contrast, the nearby Shorefront Center for Rehabilitation and Nursing Care was built in 1994 to withstand a 500-year flood (a flood with a 0.2 percent chance of happening in any given year). Its suite of backup generators supplied power for four days during an area-wide blackout, and the facility was able to provide food and shelter to many of Brooklyn's stranded residents.

Unfortunately, the example of Coney Island Hospital — which was forced to send more than 200 patients to other facilities — may be more typical of the way vulnerable populations experience climate change-related disasters.

"I visited shelters for families in the aftermath of Sandy, and they didn't have baby food, they didn’t have diapers and they didn't have cribs," Redlener said. "This is typical of what happens when you do generic planning — you end up leaving lots and lots of people out."

Cities: ground-zero for climate change impacts

New York's SIRR plan calls for about $20 billion in infrastructure improvements, including strengthening utility and transportation networks, renovating buildings and constructing seawalls and shoreline buffers, including a massive residential and commercial development named "Seaport City."

Though it's ambitious, New York's planning isn't atypical for coastal cities, which have assumed a leadership position in addressing climate-change risks since they will likely bear the brunt of its expected impacts.

Through the Urban Climate Change Research Network (UCCRN), cities are sharing scientific and economic research to support and inform decision makers in those areas, Rosenzweig said.

"We work with cities all over the world. New York is definitely one of — if not the — leader, but there are other U.S. cities that also have a longer-term history of addressing [climate change]," Rosenzweig said.

"Prime examples are Seattle, Chicago, Los Angeles, San Francisco and Miami, of course, because of their risks," Rosenzweig said.

"It's really striking that cities are emerging as the first-responders to climate change," Rosenzweig said. "It's a very exciting and very positive story — the cities are really stepping up."

Follow Marc Lallanilla on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus