Permafrost thaw and 'shrubification' have tipped Alaska's North Slope into a wildfire regime not seen for 3,000 years

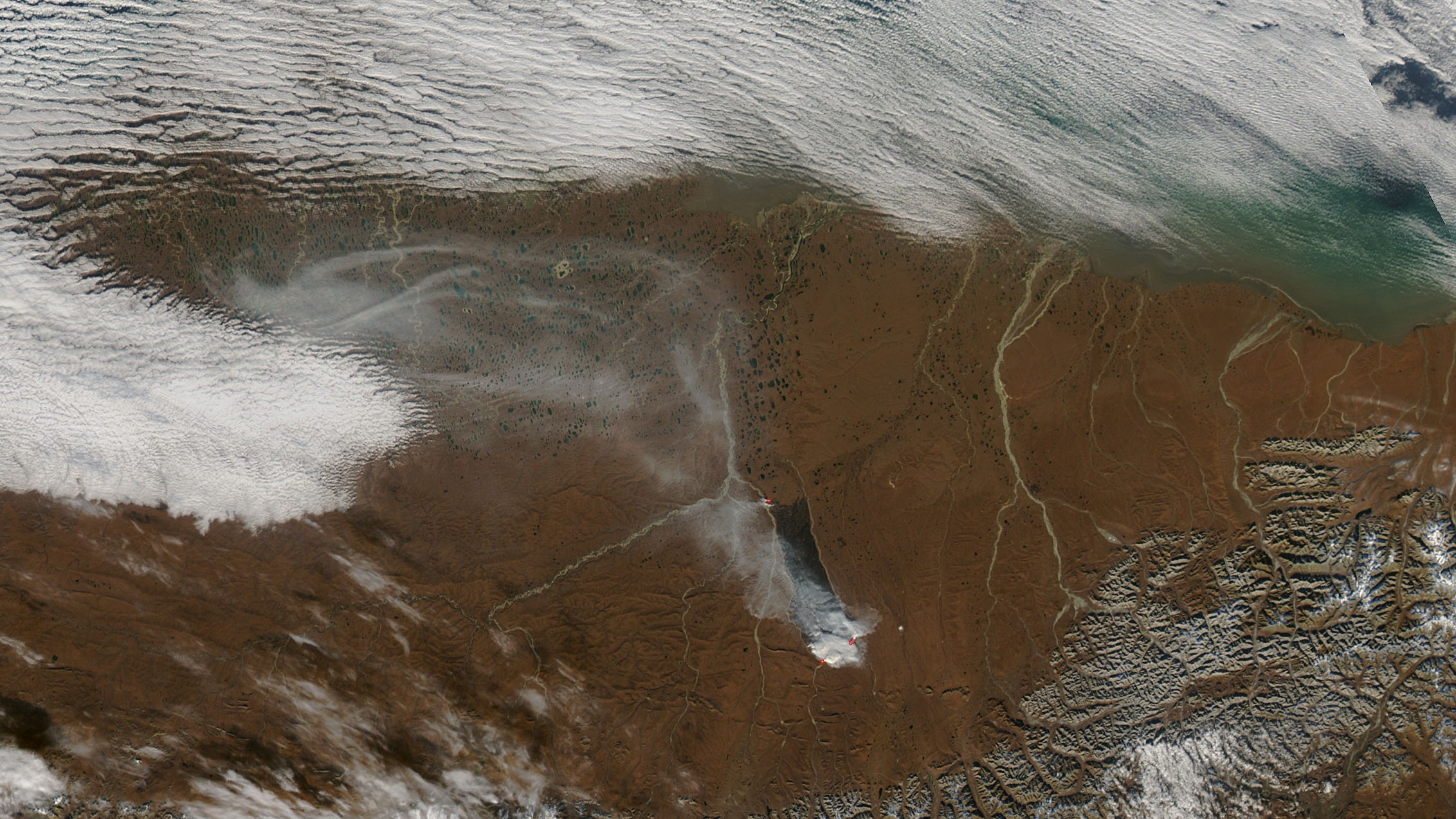

An analysis of peatland soil samples and satellite images has found that wildfires on Alaska's North Slope are more frequent and severe now than they were at any point over the past 3,000 years.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Wildfires on Alaska's North Slope are more frequent and more severe now than they have been at any point over the past 3,000 years, research suggests.

The findings are based on satellite data and ancient charcoal fragments. The research team says the increase in blazes, driven by permafrost thaw and tundra "shrubification," constitutes a new wildfire regime that will likely intensify as global temperatures continue to rise.

Fires in northern Alaska "burn in summer, when the vegetation is snow-free and dry enough to ignite," study lead author Angelica Feurdean, a paleoecologist at Goethe University Frankfurt in Germany, told Live Science. In the past, this region was dominated by sedges and mosses, which provided little fuel for fires. But recently, there has been a shift toward woody shrubs, which are far more flammable and supply much more fodder for blazes, Feurdean said.

Article continues belowResearchers previously documented an increase in wildfires over recent decades on Alaska's North Slope and elsewhere in the Arctic, but the new study contextualizes these reports by examining wildfires over past millennia.

The research, published Nov. 10, 2025, in the journal Biogeosciences, reveals that the current peak in northern Alaskan fires started in the mid-20th century and hugely exceeds wildfire activity recorded as charcoal in local peatlands since about 1000 B.C. Global warming is behind the increase, the authors say, because rising temperatures create dry conditions on land as well as moisture in the atmosphere that boosts the risk of lightning, the main source of ignition in Alaska.

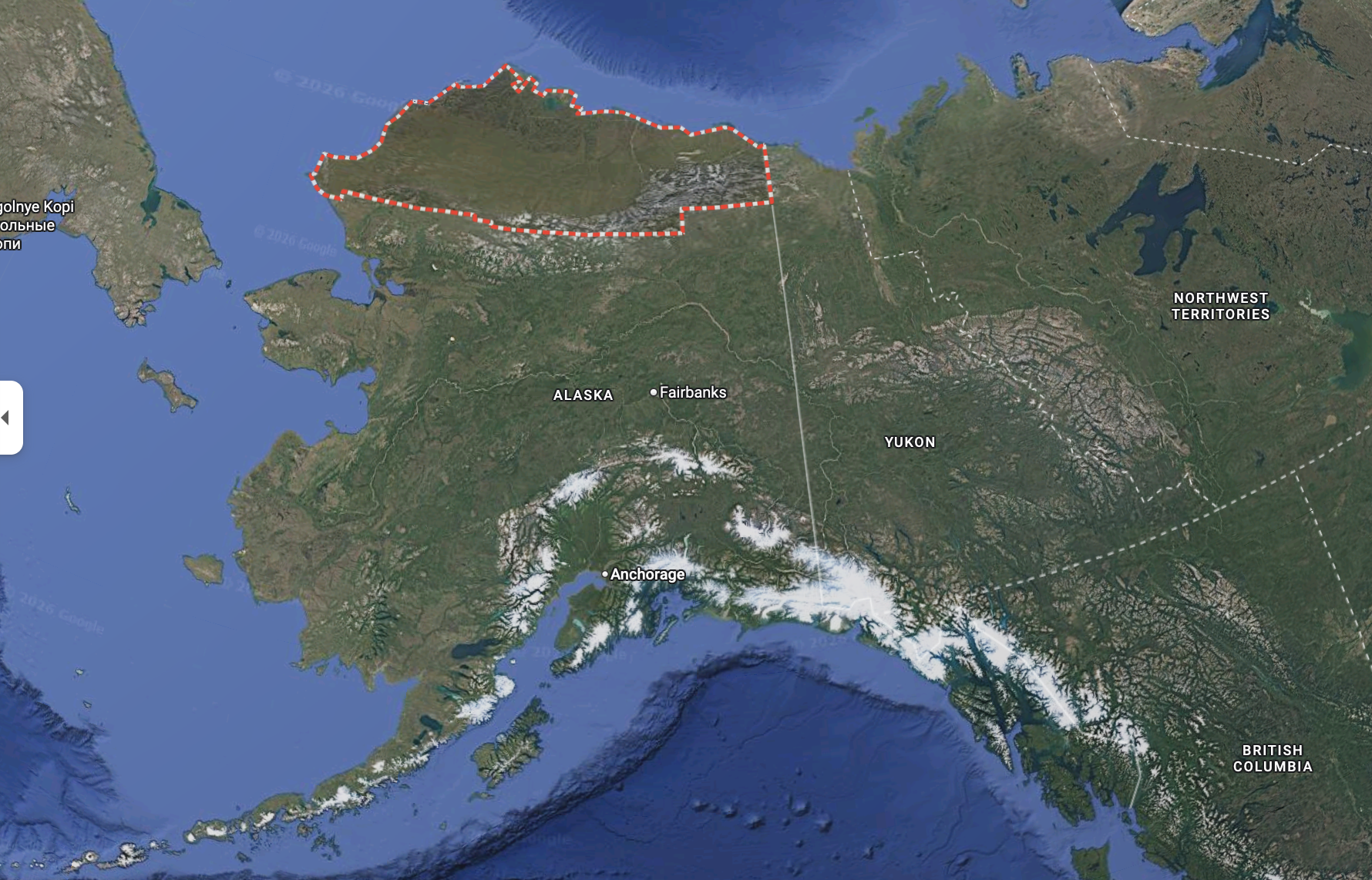

The soil samples in the study came from nine peatlands located between the Brooks Range and the Arctic Ocean. Many of these peatlands are covered in small shrubs and sphagnum moss (also known as peat moss), which only recently became widespread on Alaska's North Slope, where it replaced tussock-forming sedges such as Eriophorum vaginatum. Sphagnum moss can absorb moisture from the air, which is how it thrives despite drying conditions, Feurdean said. Sedges, on the other hand, need access to water in the soil to survive.

The samples were cores that measured about 1.6 feet (0.5 meters) long and encapsulated the past 3,000 years. The researchers analyzed the samples to reconstruct changes in vegetation, soil moisture and wildfire activity over time. Specifically, they inspected pollen and other plant remains; charcoal fragments; and tiny, single-celled organisms called testate amoebae, which are good indicators of water-table levels.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers also analyzed satellite images of wildfires north of the Brooks Range between 1969 and 2023. When they combined these images with charcoal data to reconstruct the frequency and severity of fires, they found large discrepancies in the 2000s, when satellites captured huge fires but there was minimal charcoal evidence.

One explanation is that these fires were hotter than 930 degrees Fahrenheit (500 degrees Celsius) — the threshold above which charcoal turns to ash, Feurdean said. If that's the case, then the mismatch in the data over the past two decades suggests there has been an increase in extremely intense fires, she said.

Overall, the results showed a dramatic decline in soil moisture since about 1950 due to accelerating permafrost thaw, which causes surface water to sink into the ground. Plants that depend on shallow soil moisture, such as sedges and certain mosses, were replaced by shrubs — particularly shrubs in the heath family (Ericaceae) — and sphagnum moss, leading to an explosion in plant fuel for wildfires.

Combined with a rise in temperature and lightning strikes, these effects have culminated in the most severe wildfire activity in 3,000 years, Feurdean said.

Alaska's North Slope is likely a model for what is taking place across Arctic tundra ecosystems, and we can expect wildfires to worsen if warming continues, Feurdean added.

"If you have higher temperatures, you have higher shrub cover, more flammable biomass, and then more fires," she said. "The fires will continue to be more frequent and severe."

Editor's Note: This story was updated at 10:28 a.m. ET on Feb. 12 to clarify that only satellite data and charcoal fragments, and not other data sources, were used to look at past fire history.

Article source: Feurdean, A., Fulweber, R., Diaconu, A., Swindles, G. T., & Gałka, M. (2025). Fire activity in the northern Arctic tundra now exceeds late Holocene levels, driven by increasing dryness and shrub expansion. Biogeosciences, 22(21), 6651–6667. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-22-6651-2025

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus