Surprisingly Simple Logic Explains Amazing Bee Abilities

Bumblebees and Pavlov's dogs have something in common: Both can learn to associate two things they've never seen together before.

A new study finds that bees use simple logical steps to learn from other bees which flowers hold the sweetest nectar.

"It really gives us an insight into how complex social-learning behaviors can arise in animals," said study researcher Erika Dawson, a doctoral student at Queen Mary University of London.

Scientists have long observed that bees copy other bees when learning the best spots to forage. Just by watching another bee forage through a screen, a bumblebee could go on to pick the sweetest flowers on its own, Dawson said.

"It was such a complex behavior for a little bee to perform, and that's why we thought there might be something a lot more simple behind what we were seeing," she said.

Learning to bee

Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov became famous in the early 1900s for discovering that dogs could be conditioned to salivate at the sound of a bell they associated with food. He also found that he could get dogs to drool at a completely unrelated stimulus they'd never seen alongside food. All he had to do was to link one stimulus (say, a ticking metronome) with treats. Next, he'd present the metronome sound alongside a second stimulus (say, a black square). Very quickly, dogs would start salivating at the sight of the black square, which they associated with the metronome, which they in turn associated with food. [10 Really Weird Animal Discoveries]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Dawson and her colleagues thought that bees might be taking a similar series of logical steps. To test the idea, they first showed bees a scene: six feeding platforms, three of which were occupied by model bees that looked as if they were foraging. The platforms were colorless and could only be distinguished by whether or not a bee was hanging around.

Next, the bees got to visit these platforms themselves. In some cases, the model bees were marking platforms filled with sweet sugar water. In other cases, the model bees were perched on platforms filled with quinine, the ingredient that makes tonic water bitter. This taught the bees to associate their comrades with either a sweet reward or a bitter taste.

Logical leaps

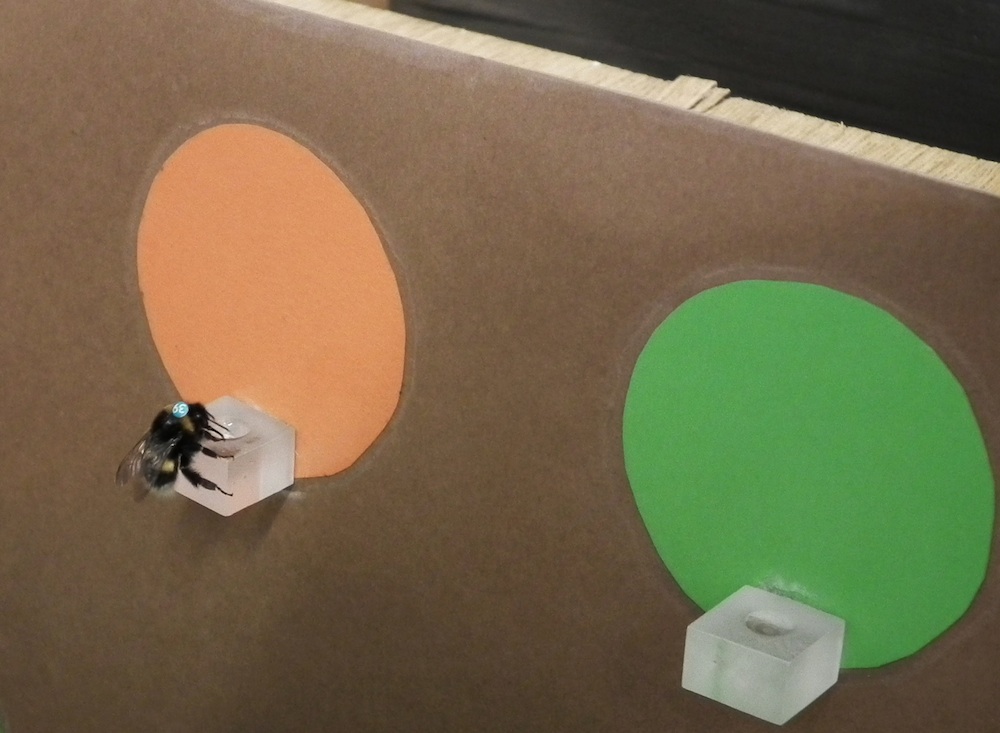

Next, the same bees observed another foraging area through a screen. This time, they saw six colored "flowers," either three orange and three green or three blue and three yellow. All flowers of one color were occupied by model bees.

After 10 minutes, the researchers removed the model bees and swapped around the placement of each color. They then let the trained bees into the foraging area and watched what they did.

Those bees that had previously learned that other bees were linked with sweets made a beeline to the color where the model bees had been. Unsurprisingly, the bees that had learned that other bees spent time around bitter quinine avoided the colors previously occupied by model bees. Bees that hadn't gone through the initial training task tried each color equally.

The study "indicates that a complex behavior that we've seen in bees is actually just a result of associations," Dawson said. Lots of animals, from sea slugs up to primates, learn by copying, she said, and the researchers hope to learn if the same simple logical leaps are behind this ability.

The study is detailed today (April 4) in the journal Current Biology.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus