The 12 Weirdest Animal Discoveries

That's Odd!

Mother Nature has a strange sense of humor. Her creations include zombie worms and penis fish, not to mention turtles with a strange way of getting rid of urine. Read on for some of the weirdest animal discoveries ever.

Note: A version of this countdown was first published on Dec. 20, 2012 and was updated and expanded on Dec. 20, 2013.

A 'tulip' with a digestive system

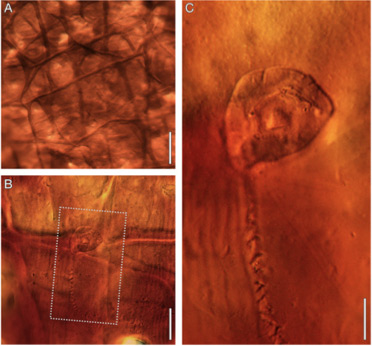

An ancient fossil found in Canada looks like a field of tulips frozen in stone. In fact, these plantlike creatures are animals unlike any seen before.

Siphusauctum gregarium, a 500-million-year-old filter feeder, was the length of a dinner knife with a bulbous "head" containing a feeding system and a bizarre gut. Instead of filtering water past its feeders externally, S. gregarium appears to have pumped water through its tuliplike head, capturing any food particles that passed through, study researcher Lorna O'Brien of the Royal Ontario Museum in Canada told LiveScience. Scientists aren't sure where this unusual creature fits into the evolutionary tree.

Bizarre creature in cocoon

Bad luck for a trapped ancient animal, good luck for modern scientists: Some 200 million years ago, a leech secreted a slimy cocoon under water or on a wet leaf, and a tiny animal the width of just a few human hairs attached itself to the new cocoon.

This bizarre little creature clung on with its springlike tail, becoming rapidly trapped and engulfed by the cocoon. The unusual circumstances resulted in something almost unheard of: the complete preservation of a soft-bodied animal with no hard bones to fossilize.

Scientists say the microscopic creature looks like it might come from the genus Vorticella. Its secret talent is coiling and uncoiling its springy stalk at a speed of 3.1 inches (8 centimeters) per second, the equivalent of a human getting across three football fields in that amount of time.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Cannibal lemurs roam the night

You don't have to be 40-feet long to be scary. This year, researchers studying the adorable gray mouse lemur (Microcebus murinus) in Madagascar came across a grisly scene: a male of the species feasting on the flesh of a dead female.

Although other primates (including humans) have been known to practice cannibalism, scientists had never before seen a gray mouse lemur so much as eat another mammal, according to ScienceNow, which reported the creepy meal. Scientists documented the case in the American Journal of Primatology.

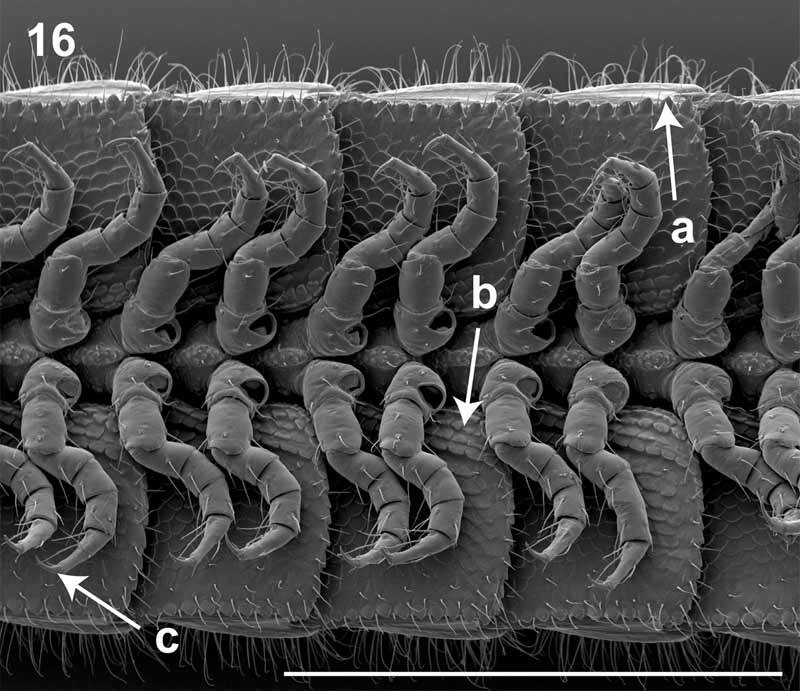

750-leg millipede

File this under "Things You Don't Want to Step on With Bare Feet:" A white millipede that manages to cram 750 wiggly legs onto its 0.4- to 1.2-inch (1- to 3-centimeter)-long body.

Illacme plenipes is the world-record holder for "leggiest creature." It's found, bizarrely, in only a 1.7 square mile (4.5 square kilometer) area in northern California — doubly odd, because the creature's closest living relative calls South Africa home. The millipedes may have spread out across the globe when most of the land on Earth was part of one supercontinent, Pangaea. When the supercontinent broke apart 200 million years ago, the relatives could have been separated, explaining the long-lost connection. [Image Gallery: The Leggiest Millipede]

A sea predator that makes T. rex look weak

Moving on to other ancient marine wildlife, here's a sea creature much scarier than an animal that looks like a flower. "Predator X," a giant marine reptile that was the top predator of the seas 150 million years ago, finally got its scientific name in 2012.

Pliosaurus funkei, as it is now properly known, was 40 feet (12 meters) long with a 6.5-foot (2 m)-long skull.

"They had teeth that would have made a T. rex whimper," study researcher Patrick Druckenmiller, a paleontologist at the University of Alaska Museum, told LiveScience.

8 tentacled snakes

How's this for a bundle of joy? In October 2012, eight snakes with tentacles were born at the Smithsonian's National Zoo.

It was not a Halloween prank. Zoo staff had been trying to breed the rare aquatic snake Erpeton tentaculatus for four years before success. These bizarre Southeast Asian serpents are the only snakes with two little tentacles on their snouts. These tentacles act like whiskers to help the snakes sense vibrations from swimming fish.

Fish with a penis head

Speaking of fish, this one has an … odd anatomy. Researchers in Vietnam's Mekong Delta reported the discovery of a fish with a penis on its head in August 2012.

Yep, a penis. And it's not just any penis — the organ includes a jagged hook for grabbing females during sex. (The female fish's genitals are located on her throat.)

The species is named Phallostethus cuulong and is one of few fish that fertilizes eggs inside the female's body rather than outside. The nasty-looking hook appendage seems to have evolved to ensure the male's sperm get to the right place. [7 Sexy Facts About Sperm]

Meat-eating sponge

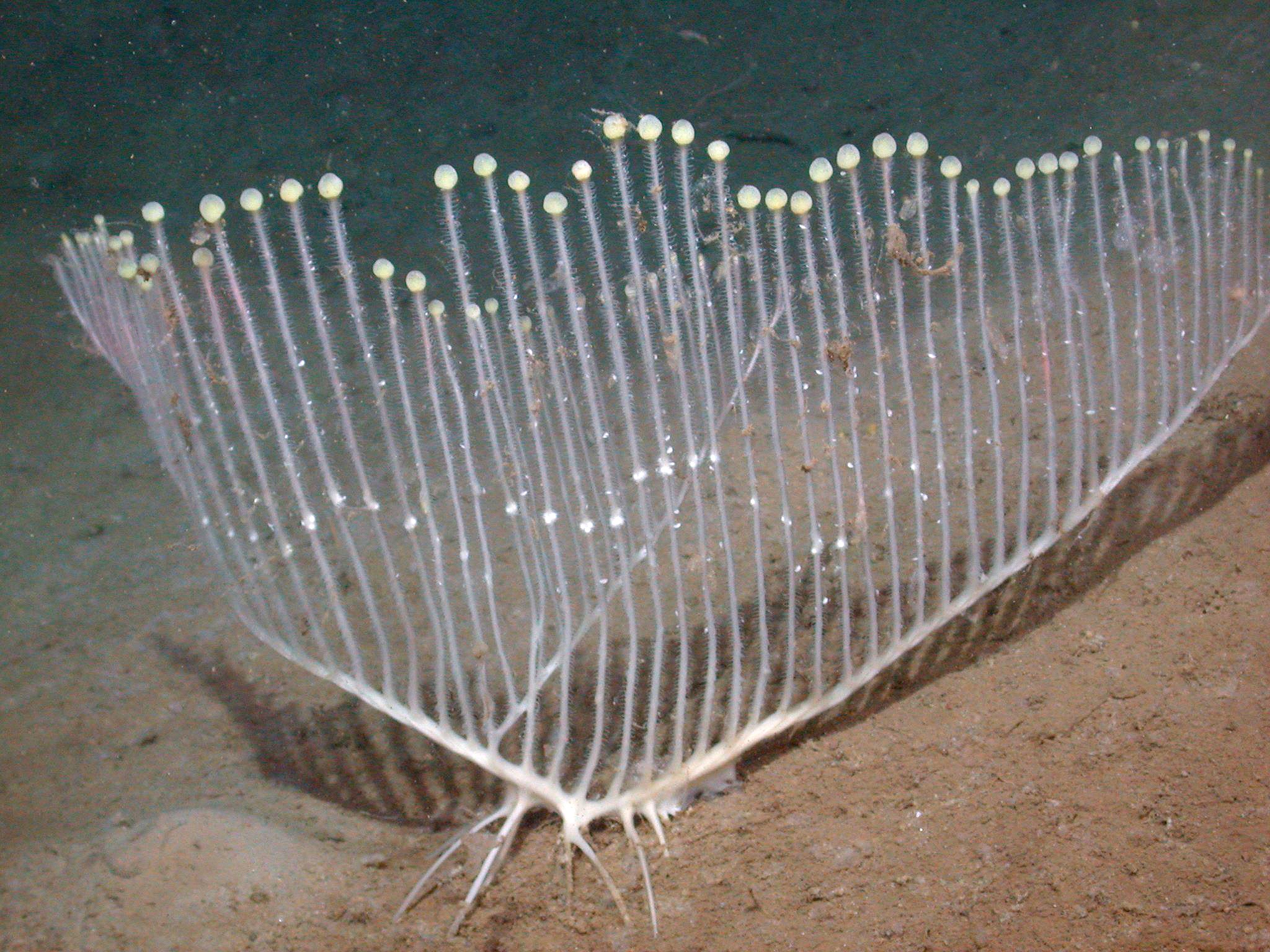

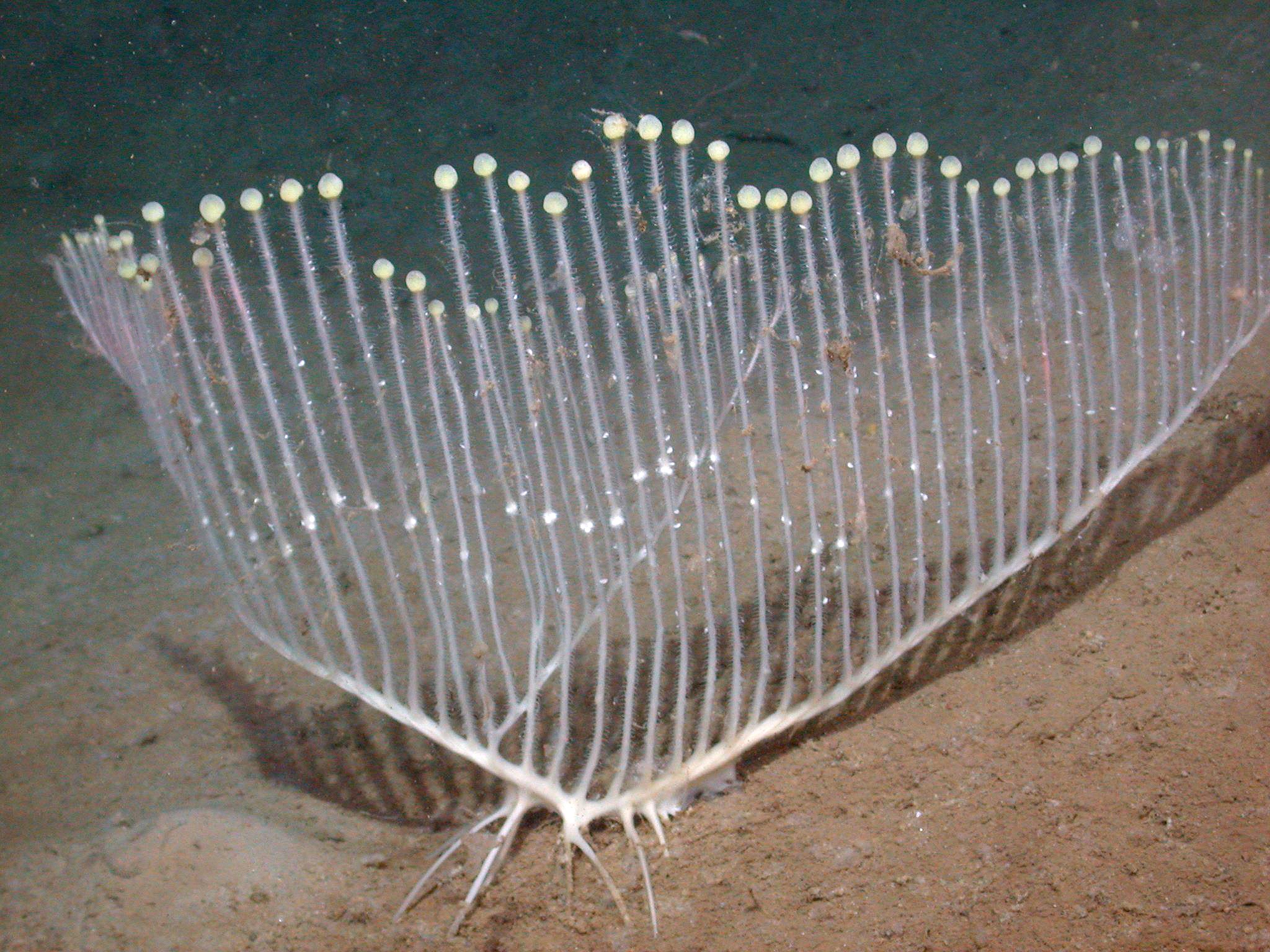

It looks like a harp or a delicate candelabra, but beware to any crustacean that gets too close: The so-called "harp sponge" will snare and slowly digest you before you know it.

This truly bizarre creature had never been observed by human eyes before 2000, when a team from the Monterey Bay Research Aquarium Institute in California took a remotely operated submersible into 2-mile (3.5-km)-deep waters off the central California coast. They later captured two specimens of the animal, which is scientifically called Chondrocladia lyra, and took 10 more video observations, reporting their analysis of the new species in October 2012 in the journal Invertebrate Biology.

The sponges feed by clinging to muddy sediment on the ocean floor and letting ocean currents wash hapless tiny crustaceans into their harplike limbs. The candelabralike branches of the limbs may help maximize how many shrimplike critters these carnivorous sponges catch.

Zombie worms

If you need even more proof of the horrors of the deep, consider the zombie worm, which feeds off the bones of whales and other scavenged sea creatures … despite not having a mouth. In July 2012, researchers at the Society for Experimental Biology's annual meeting announced that they'd figured out how this mouthless creature eats bone. It excretes acid.

The acids allow the worms to break down and absorb the bone, the researchers explained. But that's just the tip of the weirdness iceberg for these amazingly adapted worms. The females grow about an inch (3 cm) long, but males never grow larger than 1/20th of an inch (1 millimeter). They seem to live in the gelatinous tubes covering the females, serving no purpose but to fertilize her eggs.

Potty-mouth turtle

A sharp-snouted turtle found in China often submerges its head in puddles on dry land, a mystery given that these animals breathe air. Now, scientists say they've figured out why: The Chinese soft-shelled turtle (Pelodiscus sinensis) can essentially pee from its mouth.

The turtles excrete urea, the main component of urine, through the gills in their mouths, a talent previously seen only in fish, the scientists reported in October 2012 in the Journal of Experimental Biology. This may be an adaption to the turtles' salty environment. Because they can't get enough freshwater to wash urea out through their urine, they transport it through their gills and then rinse their urea-filled mouths out with saltwater. And you thought flossing was bad.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.