James Webb telescope spies a 'farting' dwarf planet with fluorescent gas in the outer solar system

New observations suggest that the dwarf planet Makemake is surrounded by faintly glowing methane gas. Scientists are unsure if the gas is contained within a wispy atmosphere or being ejected into space.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

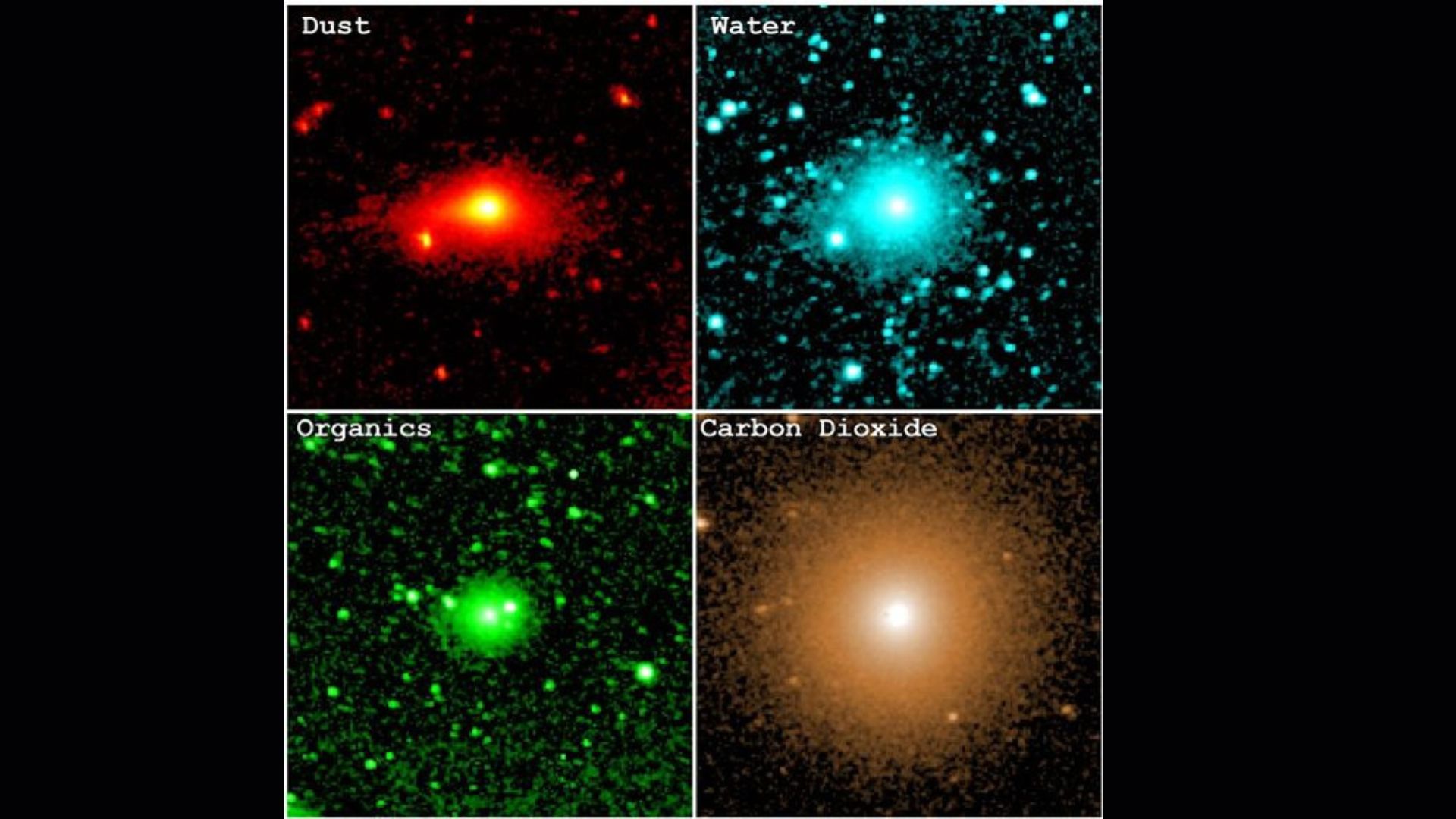

Scientists armed with the immense observing power of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) have detected faint traces of fluorescent flatulence leaking out from the dwarf planet Makemake, which lurks in the outer reaches of the solar system. This is only the second time that a gas has been detected on an object this far from Earth, and hints that this wee world is far more active than we once thought.

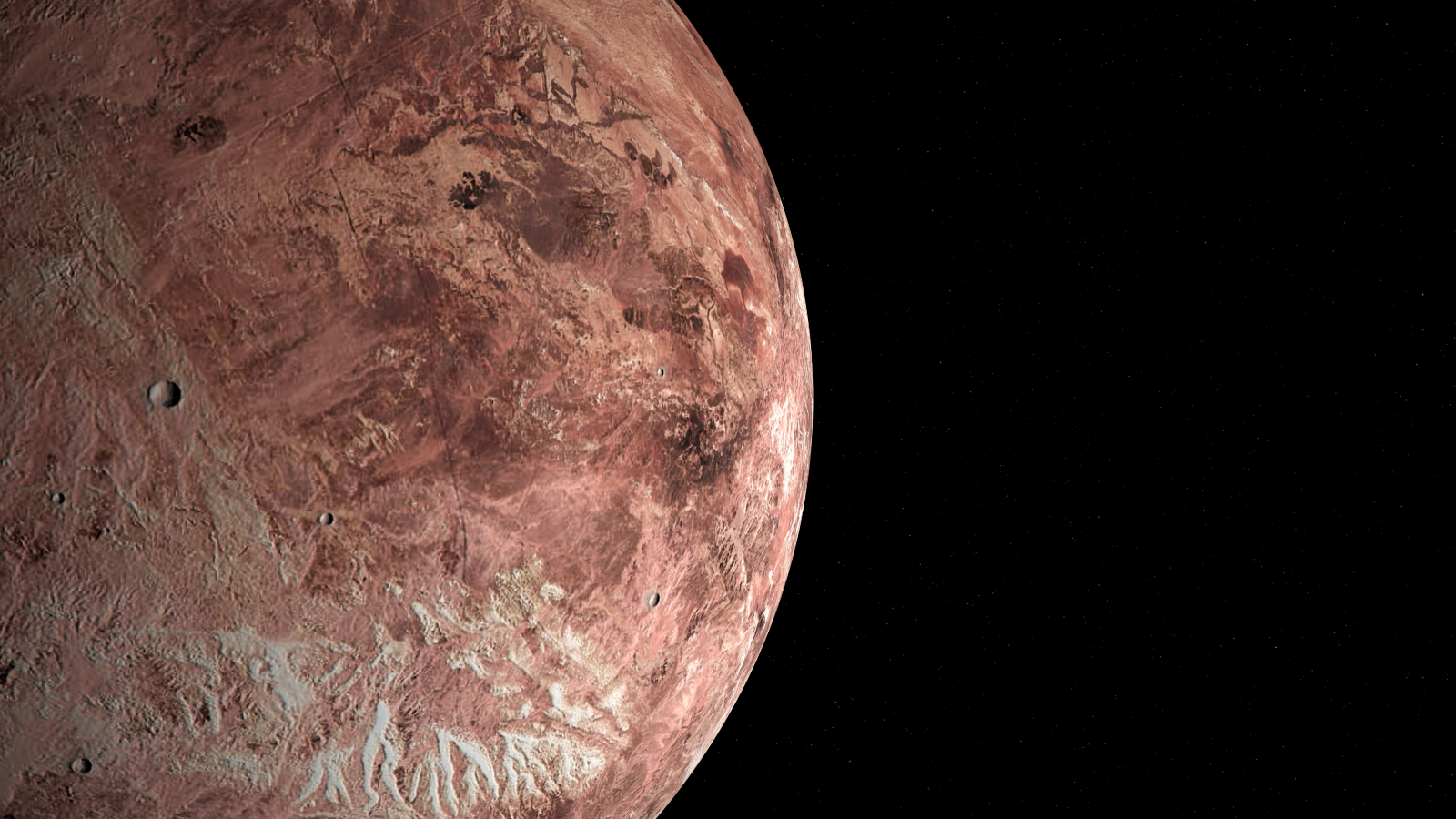

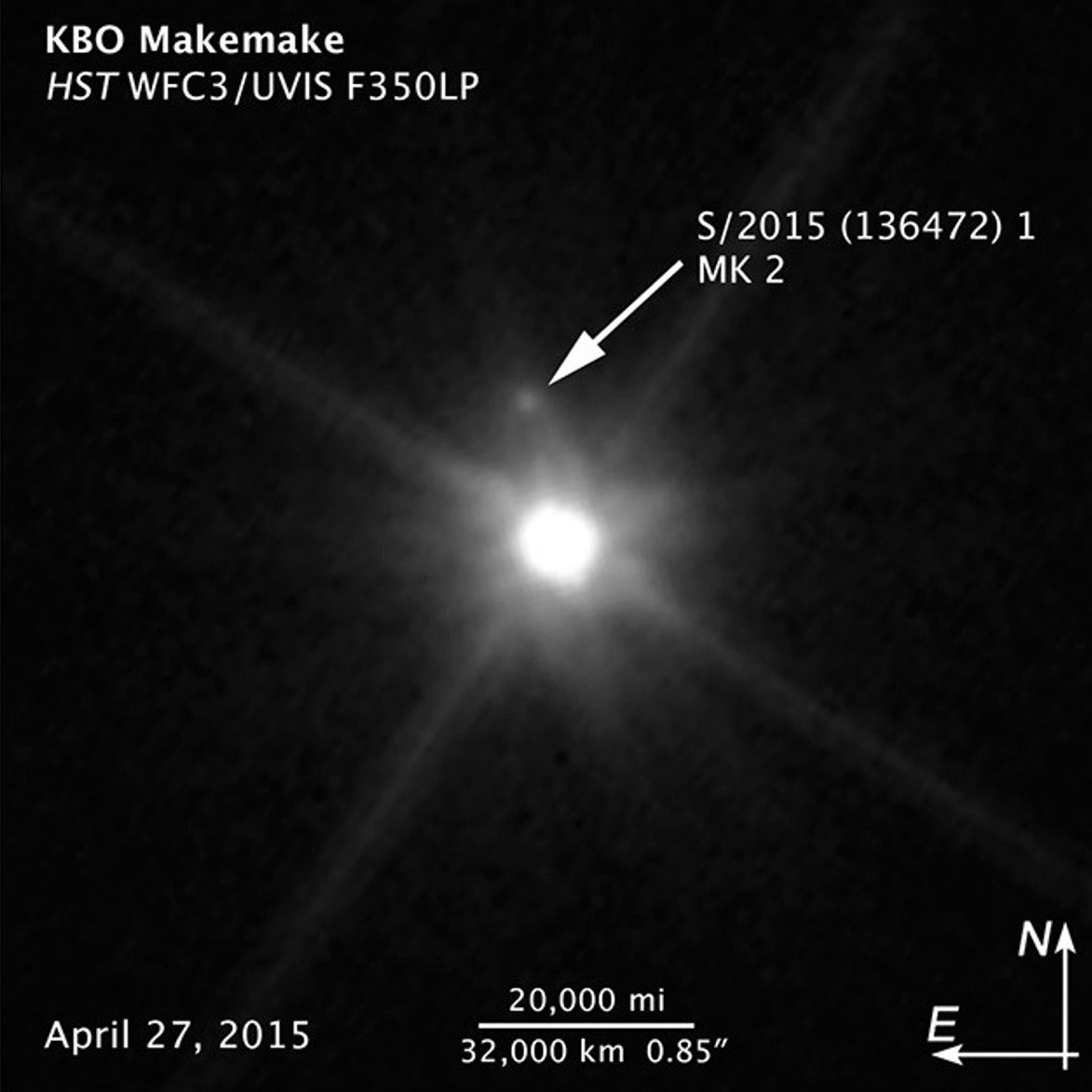

Makemake is a roughly spherical object measuring around 890 miles (1,430 kilometers) across, which is less than half the diameter of the moon. It is located around 45 times further from the sun than Earth on average, in a region known as the Kuiper Belt — a ring of asteroids, comets and larger icy objects, such as Pluto, beyond the orbit of Neptune. It was discovered in 2005 and has a small moon, dubbed MK2, which is around 110 miles (175 km) across.

Like the dozens of other dwarf planets and dwarf planet candidates within the solar system, Makemake is not considered a true planet because it has not cleared away all the debris from its orbital pathway around the sun. This is the same reason that Pluto lost its full planetary status in 2006.

Scientists have long known that Makemake's reddish-brown surface is covered with layers of methane and ethane ice, and some even think that small pellets of these chemicals, measuring around half an inch (1 centimeter) in diameter, may rest on its cold surface, according to NASA.

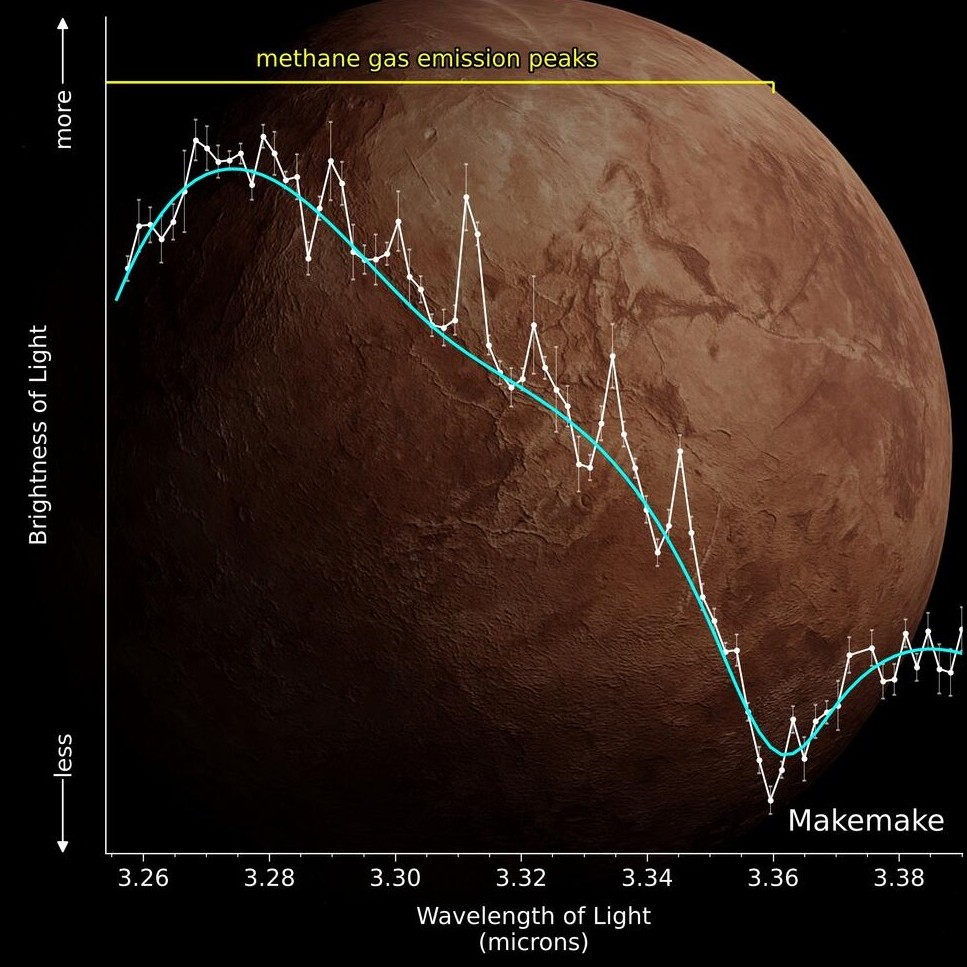

But in a new study, uploaded Sept. 8 to the preprint server arXiv and accepted for future publication in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, researchers used JWST to take a closer look at Makemake and found that the planetary dwarf also has faint concentrations of methane gas surrounding its icy surface.

"The Webb telescope has now revealed that methane is also present in the gas phase above the surface, a finding that makes Makemake even more fascinating," study lead author Silvia Protopapa, a researcher at the University of Maryland and the Southwest Research Institute in Texas, said in a statement. "It shows that Makemake is not an inactive remnant of the outer solar system, but a dynamic body where methane ice is still evolving."

Until now, the only other trans-Neptunian object (an object beyond Neptune) known to produce its own gas is Pluto, which has a very thin atmosphere composed mainly of nitrogen, with smaller amounts of methane and carbon monoxide, Live Science's sister site Space.com reported. The dwarf planet Ceres, which is located in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, also has a wispy atmosphere made up of water vapor.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

JWST spotted the methane thanks to a phenomenon dubbed "solar-excited fluorescence," which causes the gas to faintly glow as it soaks up solar radiation. Using the telescope's advanced infrared instruments, the team also measured the temperature of the gas, which is a frigid minus 387 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 233 degrees Celsius).

However, the researchers are still unsure exactly where the methane comes from, or whether it is permanently trapped within Makemake.

One possible explanation is that the methane ice on the dwarf planet's surface sublimates, or transitions from solid to gas, and is contained within a fragile, superthin atmosphere, like on Pluto and Ceres. But if this is the case, the new data suggests that the pressure in this layer of gas must be more than 1 billion times weaker than Earth's atmosphere and more than 1 million times weaker than Pluto's, making it hard to confirm if it exists.

Another possible explanation is that the gas is being ejected from beneath the object's icy surface in plumes, like on Saturn's frozen ocean moon Enceladus. This potential process, known as outgassing, could be happening at various spots across the dwarf planet, with methane shooting outward at up to "a few hundred kilograms per second," Protopapa said. But it is also very hard to tell if this is the case with the data available.

The researchers hope that follow-up observations by JWST could help solve this puzzle. But regardless of where the methane comes from, the new findings "challenge the traditional view of Makemake as a quiescent, frozen body," the researchers wrote in the paper.

Earlier in the year, another group of researchers using JWST also revealed that Makemake and another distant dwarf planet, named Eris, could be geologically active, potentially to the point where they might support life. (There are currently no planned missions to study either of the distant dwarf planets up-close.)

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus