NASA finds key ingredient for life gushing out of Saturn's icy moon Enceladus

Scientists have discovered complex molecules in the gas and vapor plumes escaping from Enceladus's icy core — and one of them, hydrogen cyanide, is a precursor for life.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

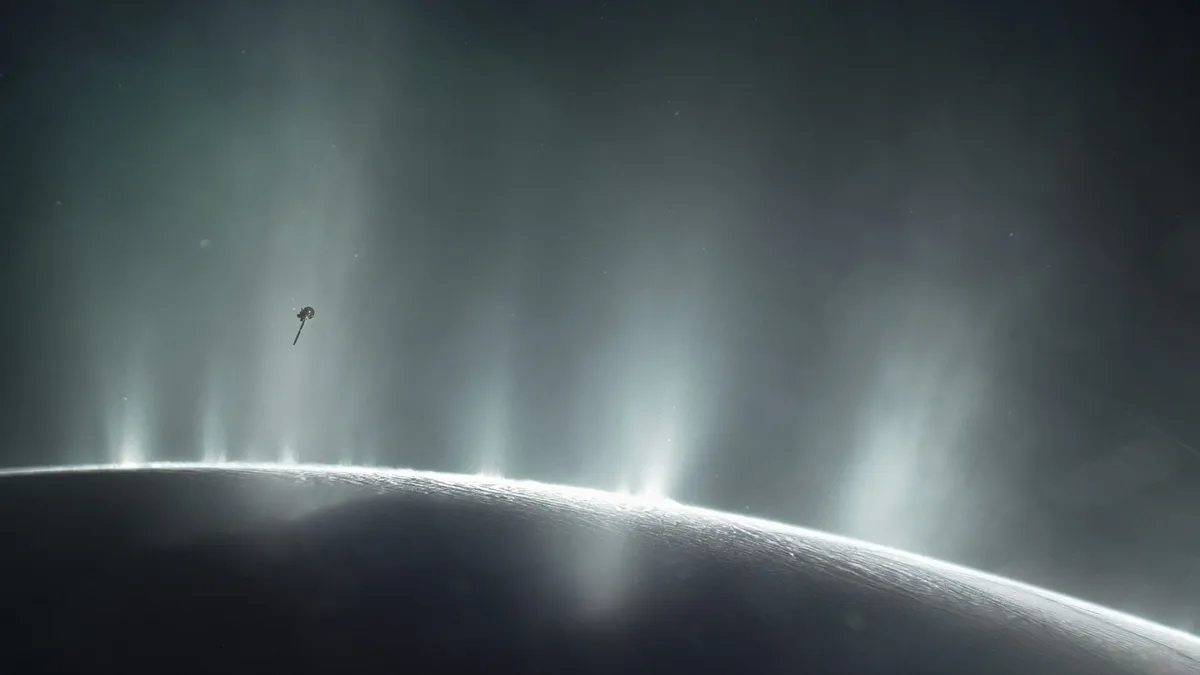

Saturn's moon Enceladus has a secret lurking beneath its icy outer crust. In the plumes of vapor jetting from its surface, scientists have detected a molecule that might be a precursor for life: hydrogen cyanide.

On Earth, hydrogen cyanide is toxic to most organisms. But scientists believe it played an important role in the early origin of life, potentially serving as a precursor molecule in the evolution of amino acids — the building blocks of proteins required for life.

"It's the starting point for most theories on the origin of life, Jonah Peter, a biophysics researcher at Harvard University and lead author of a new study on the finding, said in an interview with the New York Times. "It's sort of the Swiss Army knife of prebiotic chemistry."

Article continues belowEnceladus has intrigued astrobiologists since 2005, when NASA's Cassini probe detected jets of gas and icy crystals erupting from cryovolcanoes near its south pole. These plumes suggest that the moon might be geologically active, and that a vast, salty ocean lies beneath its frozen exterior. Previous analysis of data taken from Cassini's multiple flybys revealed that this spray is full of organic molecules, such as methane, which hint at complex chemical activity happening in the subterranean sea.

Related: Astronomers find remnants of the oldest stars in the universe

Peter and his co-authors also used data from the Cassini mission in their new study, which was published in the journal Nature Astronomy on Dec. 14. Their results confirm that something is driving organic chemical reactions in Enceladus's ocean — and that it might be releasing more energy than previously thought. In addition to hydrogen cyanide, the researchers detected a cocktail of oxidized organic molecules, which wouldn't be possible to synthesize without significant energy input.

"If methanogenesis is like a small watch battery, in terms of energy, then our results suggest the ocean of Enceladus might offer something more akin to a car battery, capable of providing a large amount of energy to any life that might be present," Kevin Hand, an astrobiologist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory and co-author of the study, said in a statement.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

While this by no means confirms the presence of life, it does strengthen the case for it on Enceladus. But the icy moon is far from the only candidate for life elsewhere in our solar system. Scientists are also eager to probe the oceans of Jupiter's moon, Europa, and another of Saturn's moons, Titan. They are also still scouring the surface of Mars, as well as the clouds drifting through Venus's upper atmosphere, looking for alien microbes that might be living there.

Whether or not one of these candidates yields extraterrestrial life, researchers can learn a lot more about how the chemistry and origins of life on our own planet emerged by studying these neighboring worlds.

Joanna Thompson is a science journalist and runner based in New York. She holds a B.S. in Zoology and a B.A. in Creative Writing from North Carolina State University, as well as a Master's in Science Journalism from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. Find more of her work in Scientific American, The Daily Beast, Atlas Obscura or Audubon Magazine.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus