Superhot 'Dragon's Breath' Chili Pepper Can Kill. Here's How

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Death by chili pepper may not be a common way to die, but it's certainly a possibility for unlucky souls adventurous enough to try Dragon's Breath, the new hottest pepper in town.

Mike Smith, the owner of Tom Smith's Plants in the United Kingdom, developed the record-breaking pepper with researchers at the University of Nottingham. He doesn't recommend the pepper for eating, however, because it may be the last thing a person ever tastes.

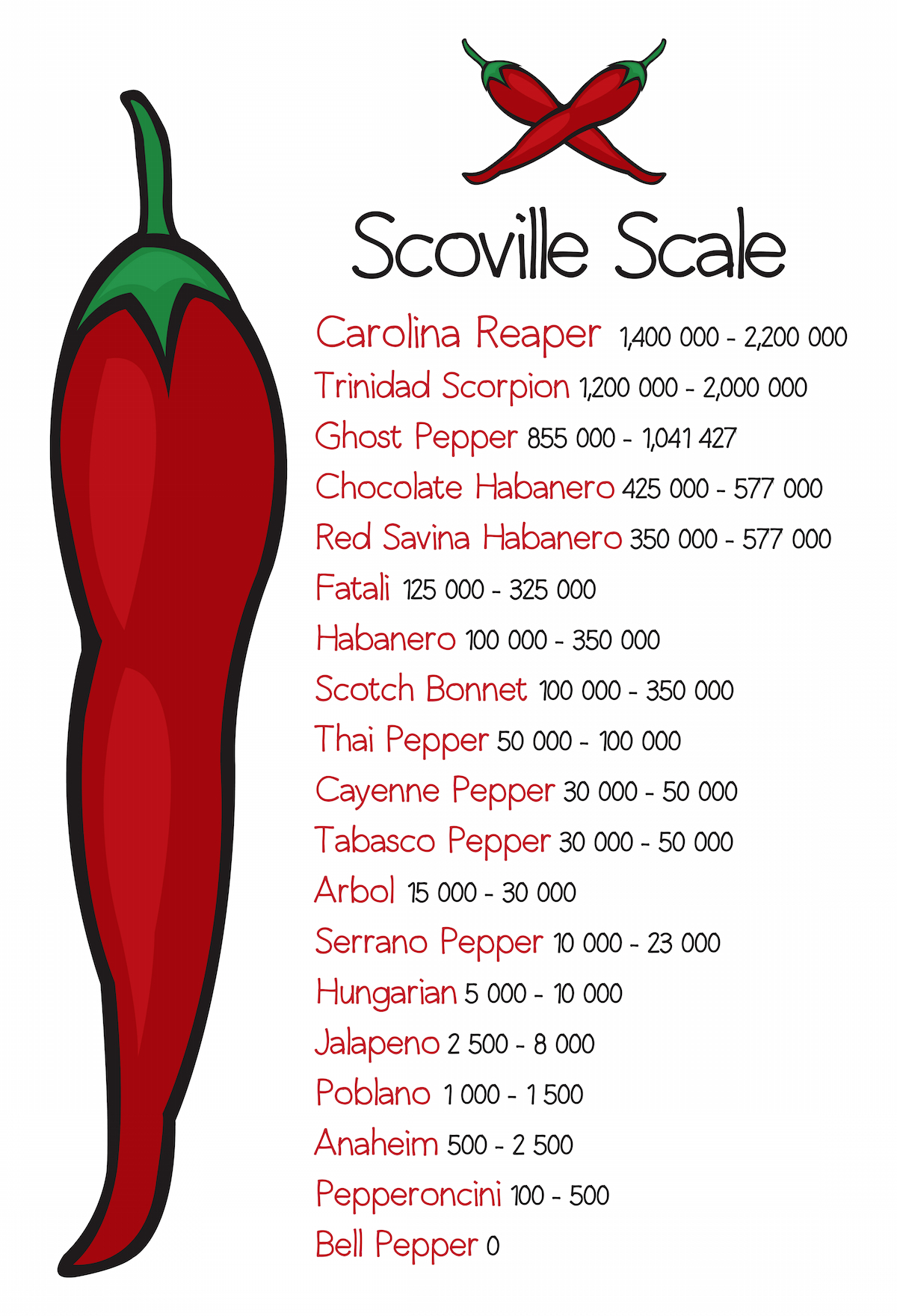

So how exactly do hot peppers, such as Dragon's Breath, maim or kill those who try to eat them? Let's start with the pepper's spicy stats: Dragon's Breath is so spicy, it clocks in at 2.48 million heat units on the Scoville scale, a measurement of concentration of capsaicin, the chemical that releases that spicy-heat sensation people feel when they bite into a chili pepper. Dragon's Breath is hotter than the current record-holder, the Carolina Reaper, which packs an average of 1.6 million Scoville heat units, as well as U.S. military pepper sprays, which hit about 2 million on the Scoville scale, according to the Daily Post.

In comparison, the habanero pepper is downright mild at about 350,000 Scoville heat units, as is the jalapeño pepper, which registers at up to 8,000 heat units, according to PepperScale, a site dedicated to hot peppers. Bell peppers have a recessive gene that stops the production of capsaicin, so they have zero heat units, PepperScale reported. [Tip of the Tongue: The 7 (Other) Flavors We Can Taste]

Dragon's Breath, in contrast, is so potent that it will be kept in a sealed container when it goes on display at the Chelsea Flower Show from May 23 to 27 in London, the Daily Post reported.

"I've tried it on the tip of my tongue, and it just burned and burned," Smith told the Daily Post. "I spat it out in about 10 seconds."

Spicy havoc

When a daredevil, such as Smith, eats an exceptionally spicy pepper, the first sensation is usually mouth numbness, according to Paul Bosland, professor of horticulture at New Mexico State University and director of the Chile Pepper Institute.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"What's happening is that your receptors in your mouth are sending a signal to your brain that there's pain, and it's in the form of hotness or heat, and so your brain produces endorphins to block that pain," Bosland told Live Science previously.

However, unusually hot peppers go beyond numbing the mouth. When these extreme examples are eaten, the body inflates liquid-filled "balloons," or blisters, in areas exposed to the concentrated capsaicin, including the mouth and (if swallowed) the throat, Bosland said. These blisters can help absorb the capsaicin's heat.

"The body is sensing a burn, and it's sacrificing the top layer of cells to say, 'OK, they're going to die now to prevent letting the heat get farther into the body,'" Bosland said.

Some peppers, such as Dragon's Breath, are so hot, that blistering alone would not contain the heat. Rather, their capsaicin permeates the blisters and continues to activate receptors on the nerve endings underneath them, which can lead to a painful burning sensation lasting at least 20 minutes, Bosland said.

In some cases, people vomit up the pepper, as did one 47-year-old man in California who ate a burger topped with ghost pepper puree, according to a 2016 case report in the Journal of Emergency Medicine. The man vomited so violently, he ruptured his esophagus and needed medical attention, Live Science reported.

The immune system can go into overdrive if the capsaicin is too concentrated. That's because TRPV1 receptors — proteins on nerve endings that detect heat — are activated by capsaicin, and erroneously interpret capsaicin as a signal of extreme heat, Live Science reported previously. This mistake can send the body's burn defenses through the roof. [Why Does Your Nose Run When You Eat Spicy Food?]

In some cases, eating a hot pepper can lead to anaphylactic shock, severe burns and even the closing of a person's airways, which can be deadly if left untreated, according to the Post.

However, Smith didn't intend for Dragon's Breath to be part of a meal. Instead, he grew it so that it could be used as a topical numbing anesthetic for people who are allergic to regular anesthetic.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus