3D Laser Scanner Makes Haunting Works of Art

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Two historians on a mission to preserve historic structures in Ethiopia inadvertently turned a cutting-edge 3D scanning device into a tool for creating works of art.

Lidar technology uses pulses of laser light to map the contours of 3D surfaces and structures.

For example, 2D photographs can capture the major features of a landscape, but lidar reveals every dip, ditch and rise. It shows the full size of boulders, the depth of canyons. Some lidar technologies can see through foliage, and have been used to hunt for lost cities buried in the jungle. Similarly, 2D photographs of sculptures and frescoes lose an entire dimension of the art work — it would be like photographing a Van Gogh painting in black and white. [See More Amazing 3D Lidar Works of Art]

Lidar is used extensively in the oil and gas industry for surveying landscapes, but its list of uses is expanding.

Currently, lidar devices are too slow to image moving objects, like people; but when Charles Matz and Jonathan Michael Dillon went to Ethiopia to take 3D scans of the city's historic structures, they ended up also scanning images of the people who live there today. The results are beautiful and haunting representations of the people living in this historic city.

The science of lidar

The city of Harar, Ethiopia, is listed as a UNESCO world heritage site and is considered the fourth holiest city of the Muslim religion, after Mecca, Medina and Jerusalem. The city contains many historic structures, such as the five gates of Harar that once served as entrances to the city's different neighborhoods. But the gates were built out of mud brick in the 1500s, and today are crumbling, along with many other pieces of the city's historic architecture.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

While it would take a small fortune to physically preserve or restore the city's crumbling structures, Matz and Dillon wanted to at least preserve them digitally.

Matz had already created 3D scans of frescoes at the Scuola Grande di San Rocco in Italy. The scans, unlike optical photographs, preserve the contours and depth of those structures.

The team worked with the Regional Governorate of Harari State on a project to scan many of the city's structures with lidar.

According to the National Ocean Service, lidar stands for light detection and ranging, although some sources say the word was created as a combination of the words "light" and "radar."

The lidar technology used by Matz and Dillon is based on a simple idea: a device about the size of a microwave sends out individual pulses of laser light. A pulse hits a surface, bounces off it and returns to the box. The detector in the box measures the time it took the pulse of light to return, or it's time of flight. The time of flight of each pulse is what the software then uses to determine how far away an object is, which helps build a 3D map of the structure. [Images: One-of-a-Kind Places on Earth]

After the first scan, the device is then moved to a different location in the same area, and once again sends out millions of laser pulses. Sometimes the laser source is moved multiple times in the same area, which increases the 3D resolution of the scan. Combining multiple scans of the same area creates a fully 3D image that can be rotated and studied from different angles.

"You can explore the virtual model [on] the computer — move around in it, walk around in it," Matz said.

Different types of lidar exist for different purposes. Those used by the oil and gas industry are operated from an aircraft, and are used to create detailed maps of the contours of a landscape. Lidar has been used to study cities and landscapes following earthquakes and other natural disasters. In some cases, this can help geologists understand how earthquake faults behave.

Other lidar devices can be focused on very small details, like finding imperfections and defects in structures that need to be structurally perfect. Lidar devices used in aerospace engineering, for example, can create such precise images that they can reveal a hairline crack in a jet engine.

In crime-scene forensics, lidar once again offers a more detailed alternative to 2D pictures and helps prevent contamination of crime scenes. Specialized software packages make it possible to use lidar to identify blood spatter or bullet trajectories, and to gauge the heights of witnesses or suspects.

Lidar technology originated in the 1960s. NASA used lidar during the Apollo 17 mission in 1972 to image the surface of the moon. But Matz said it has only recently become more accessible to nonindustrial users, through lower-cost scanning units and scanning units that can be leased, not bought.

History into art

Matz and Dillon went to Harar in 2011, and with the help of the Regional Governorate, began scanning the city's historic structures.

"Harar is off the beaten track and in a remote part of eastern Ethiopia," Matz wrote in an email. "It is a market crossroads in an agricultural region. It is ancient still in its mannerism and exchanges." The areas of Harar visited by Matz and Dillon often hosted markets where people were selling food and goods out of stalls, or off blankets on the ground. Each morning, a group of governorate personnel would arrive and clear people out of the area that Matz and Dillon were surveying.

"One day they were late, and we went out anyway and started to scan while the market was still going," Metz said.

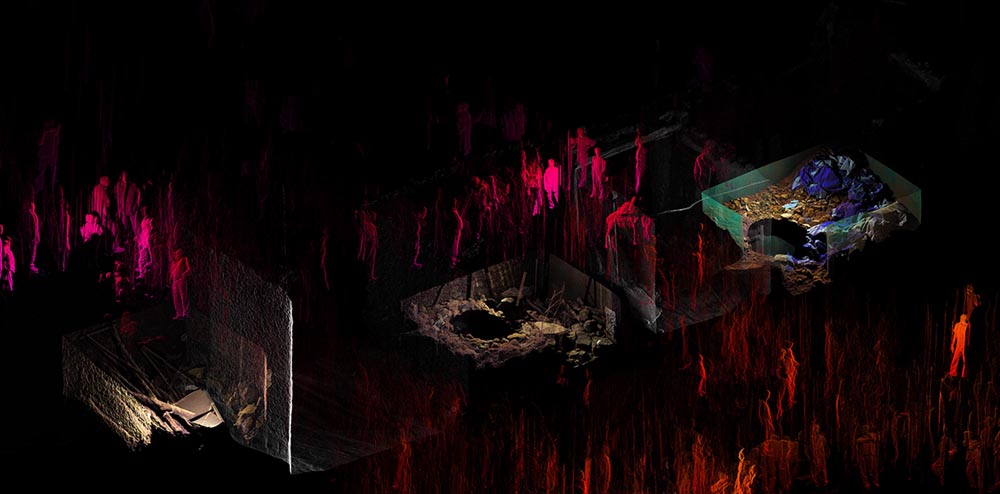

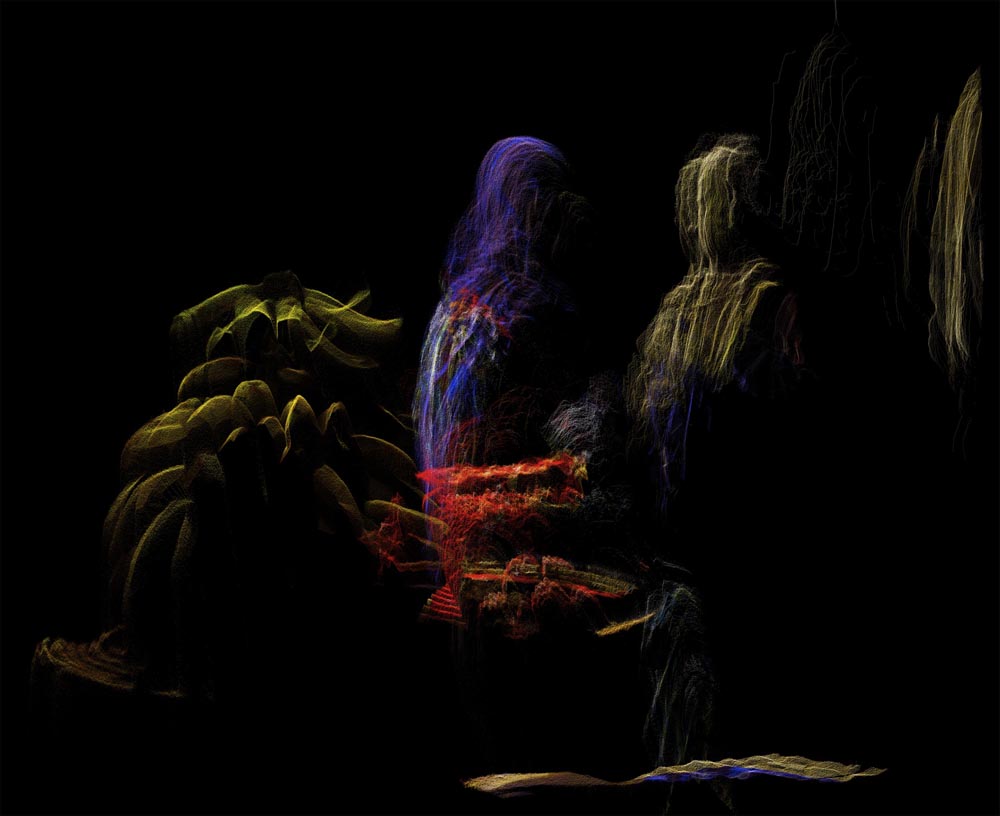

In the images that the team captured, the people are blurry and often look as though they were sketched with vertical pencil lines — the shapes of their bodies are apparent, but their features are lost. Each lidar scan takes about 9 seconds, and two to three scans are needed to get a 3D map. If a person moves before the lidar device is done collecting the light, the laser pulses will bounce off their faces or bodies multiple times, so that multiple reflections are captured by the device and added to the image. It gives the impression of movement and impermanence, set against the buildings, which look steady and unmoving.

Harar is a colorful city: the buildings are painted in bright blues, while the women wear vibrantly colored fabric in yellows, reds and purples. But in the lidar images, these bright colors stand out against smooth, unnaturally black backgrounds. This is where the laser pulses have traveled out into space and never encounter a surface to bounce off of, so the machine receives no data about those areas. In the final images, it looks as though the city sits on the edge of an abyss. [In Photos: World Heritage Sites Dazzle with Culture & Beauty]

One particularly striking image shows a boy against a pitch-black background, dragging a stick in the dirt. His clothes are captured in brilliant detail by the lidar system — even the texture of the fabric is apparent. But his head appears split in half.

"I think he turned his head in the middle of the scan, and we recorded it, and the resulting 3D model had this cleft in it. That's what gave it that haunting expression," Matz said. Talking through a translator, the boy told Matz and Dillon he was an orphan.

"We were told that many young boys travel in groups to look for agrarian, farm hand work far from their birthplaces and that many came from the conflict zone as their parents may have been killed," Matz wrote in an email. Matz said the boy's story adds a "thematic message" to the image. "I think that thematic message is what makes this "art," rather [than] simply a piece of the scientific study."

Artistic tools for the future

Matz said there are a few other groups who have experimented with lidar for creating visual art, but he doesn't know of anyone else doing so with human subjects. The slow speed of the scanning technology makes it prohibitive to use as an imaging tool for moving objects.

"[Lidar] technology hasn't quite developed where it can accumulate this information quickly because the data sets are very dense. We're talking gigabytes and gigabytes of information," Matz said. Big budgets can buy faster computer processors, but for many users, the high data output is prohibitive. Matz draws a parallel between lidar's current state and the state of early optical photography, when the technology also required very long exposure times. As lidar technology becomes faster, Matz thinks it will become more commonly used for artistic and aesthetic applications.

The lidar images of Harar will preserve the city's infrastructure, but Matz says eventually he'd like to see a full 3D replication of the city available online for people who want to explore the area but can't travel there in person.

"We're interested in providing virtual walk-throughs or access to works of art without having to actually visit the space," Matz said. "So, for example, many of these World Heritage Sites are inaccessible or very hard to get to. We're interested in recording them and making them available as public domain so people can experience what these places are like on the computer."

Matz said he is looking for a place to host these virtual tours, and is gathering more location scans. He is now in talks with the representative of Nomad Two Worlds, an artistic collaboration created by the photographer Russell James and native aboriginal groups, to acquire permission to scan a sacred site in Western Australia that is closed to visitors.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus