From Brain Control to Multiverses, 'Rick and Morty' Gets Some Science Right

But don't get your hopes up about time travel.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Hyperintelligent cyborg dogs. Parasitic alien shape-shifters. Portal guns that open gateways between dimensions. A nanoscale amusement park in a living human body, with a pirate-themed ride through the pancreas.

The sci-fi world of the popular animated series "Rick and Morty" is bizarre and fantastic. In episode after episode, rogue scientist Rick Sanchez demonstrates that he's the smartest person — and possibly the most dangerous one — in this and other universes, as he brews concentrated dark matter or steals energy-generating crystals from a post-apocalyptic hellscape. Whether Rick and his inventions will save humanity or guarantee its annihilation is never certain until the credits roll.

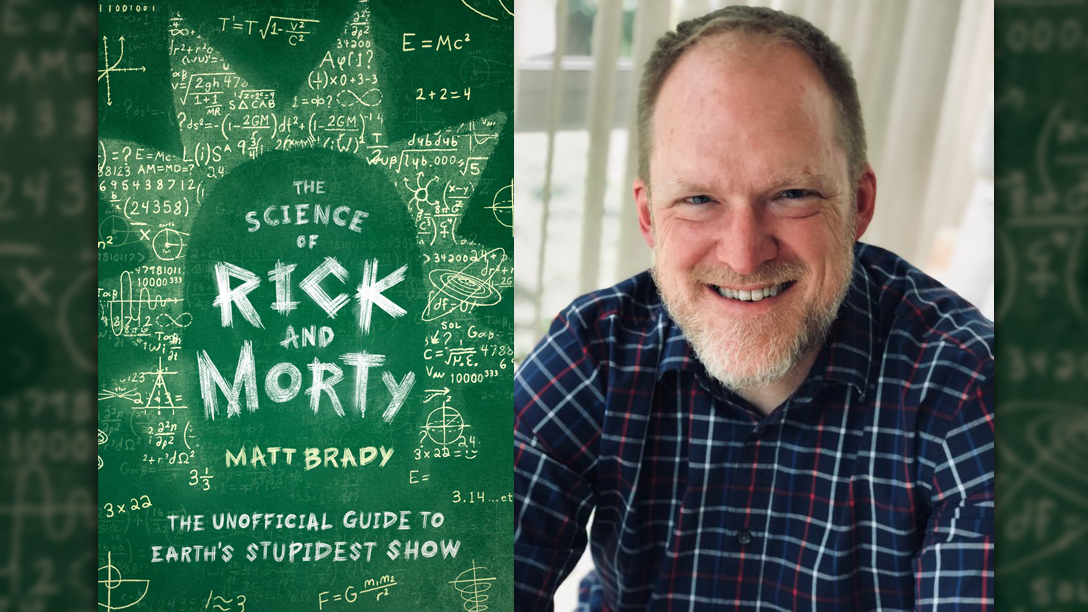

But while devices such as Rick's multiverse-crossing portal gun may not exist in the real world, the scientific concept of multiverses — multiple copies of the universe that coexist invisibly — is certainly real. And that's not the only kernel of genuine science seeded throughout the program, according to a new book, "The Science of Rick and Morty: The Unofficial Guide to Earth's Stupidest Show" (Atria Publishing Group), available today (Oct. 1).

Related: Top 5 Reasons We May Live in a Multiverse

Much of the humor in "Rick and Morty" isn't what you'd call intellectual; the show wallows in gross-out gags and bathroom jokes. But while the comedy might often be silly, much of the science is serious stuff. From memory hacking to time freezing, from people-shrinking to human-habitable exoplanets, "throughout the series, they've touched on some really big ideas," said the book's author, Matt Brady, co-founder and former editor-in-chief of comic book news website (and Live Science sister site) Newsarama, and a high-school science teacher.

"It's my hope that with or without this book — with, I hope! — people watching the show will go, 'That's interesting, I wonder if it's real?' Then, they'll check it out and maybe learn a bit of science," Brady told Live Science.

"Rise above. Focus on science."

In one memorable episode, "Pickle Rick," a transformed Rick (now a pickle) traps a cockroach and takes control of its body by manipulating the insect's brain with his tongue. Scientists may not be able to turn themselves into pickles, but researchers have demonstrated that they can control cockroaches' nervous systems through brain stimulation, Brady said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Precise anatomical location aside, there is a spot in the insect brain that, if you poke it, you'll get legs to move (among other things): It's called the central complex," Brady wrote in the book.

Rick's tongue, saturated with potassium and sodium, disrupts the bug brain's electrochemistry to send commands to the roach's limbs. In the real world, there are even kits that provide all the necessary tools for creating cyborg roaches that can be controlled remotely — though, not with the user's tongue, Brady told Live Science.

"It takes a little bit of cockroach surgery, and it's not for the faint of heart," he warned.

Multiverses, a staple of the "Rick and Morty" world, have also been proposed and championed by scientists, Brady wrote. Brian Greene, a professor of physics and mathematics at Columbia University in New York City, has produced a model of nine multiverses, and Max Tegmark, a physics professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, has suggested that there are up to four multiverses.

These hypotheses and others use physics principles to delve into the possible existence of other, unseen universes. The observable universe occupies space-time fabric, a continuum of time combined with 3D space. Because the precise composition of space-time is unknown, scientists can't rule out that it contains infinite copies of the universe that we simply can't see.

Related: The 18 Biggest Unsolved Mysteries in Physics

"A large number of physicists now believe at least one version of what Greene and Tegmark have proposed, or something very close to it," Brady wrote. Though it's possible we do inhabit a multiverse, "figuring out what type of multiverse, that's going to be the trick," Brady said. Even the infinite multiverses in "Rick and Morty" — and infinite copies of every person — are within the realm of possibility, he added.

"If there are infinite repeats of particles, Earths will show up over and over again. How many? An infinite number. How many copies of me are out there? An infinite number. It's one of those thoughts I'd introduce to my physics students. I'd say, 'You're going to think about this, and you're going to want to lie back and stare up at the sky for a very long time and just say, whoa.'"

"We're all gonna die. Come watch TV."

For now at least, multiverses remain a concept for computer models and thought experiments. By comparison, some of the hands-on science in "Rick and Morty" raises serious ethical questions that real-world scientists frequently confront. Rick's choices and actions, however, generally reflect his own agenda rather than bending to conventional morality, said Brady.

"'I wouldn't say that 'Rick and Morty' is the place to go for ethical or moral guidance in science," he said.

Take cloning, for example, which Rick uses in several episodes (to send a younger version of himself to high school to hunt vampires, to create a duplicate of his daughter Beth so she can abandon her family, to replace Beth's childhood friend Timmy and save Timmy's father from execution for committing cannibalism). A clone is an organism created from identical copies of genetic information that came from another animal. Scientists have been successfully producing mammal clones since Dolly the sheep was cloned in 1997, through a process known as reproductive cloning.

Recent cloning success stories include a clone of the so-called Sherlock Holmes of police dogs and puppies that are reclones of a cloned canine. Researchers have even cloned monkeys, coming one step closer to cloning another primate: people.

However, while scientists say it's biologically possible to clone a human, the extraordinarily high risk of developmental deformities and death make such an endeavor extremely unethical.

And even though Rick seemingly acts without concern for ethics, he frequently has to address the harm his science causes. As a result of one experiment, he and Morty abandoned their version of Earth because Rick, in trying to fix a wayward love potion's effects, accidentally turned nearly all people on the planet into hideous monsters.

"In 'Rick and Morty,' the lesson of unintended consequences is always there," Brady said.

"To paraphrase Jeff Goldblum [playing chaos theory mathematician Ian Malcolm in "Jurassic Park"], 'You can do this, but should you do this?' That's one of the strong arguments that we've historically made in science," Brady added.

"The Science of Rick and Morty: The Unofficial Guide to Earth's Stupidest Show" is available online at Amazon and Barnes & Noble and at other booksellers.

- 'Star Wars' Tech: 8 Sci-Fi Inventions and Their Real-Life Counterparts

- 8 Mammals That Have Been Cloned Since Dolly the Sheep

- Doom and Gloom: Top 10 Post-Apocalyptic Worlds

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus