Facts About Potassium

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Kaboom! Pure potassium is a highly reactive metal. Exposed to water, it explodes with a purple flame, so it's usually stored under mineral oil for safety.

Because it's so reactive, potassium isn't found free in nature, according to the Jefferson National Linear Accelerator Laboratory. However, minerals and compounds containing potassium are common: It's the seventh-most abundant element in Earth's crust.

Naturally occurring potassium salts such as saltpeter and potash have been used for centuries, but no one isolated potassium until 1807, when Cornish chemist Humphry Davy had the notion to run an electric current through some wet potash (potassium carbonate). The current broke the bonds holding the compound together. Davy would later repeat the trick in order to discover sodium, according to the Chemical Heritage Foundation.

It was Davy, according to the Royal Society of Chemistry, who first noted potassium's explosive purple reaction to water, seen here. The conflagration occurs because the combination of potassium and water creates potassium hydroxide (KOH) and hydrogen gas, as well as heat. The heat ignites the hydrogen gas, and the whole shebang goes boom.

Just the facts

According to the Jefferson National Linear Accelerator Laboratory, the properties of silver are:

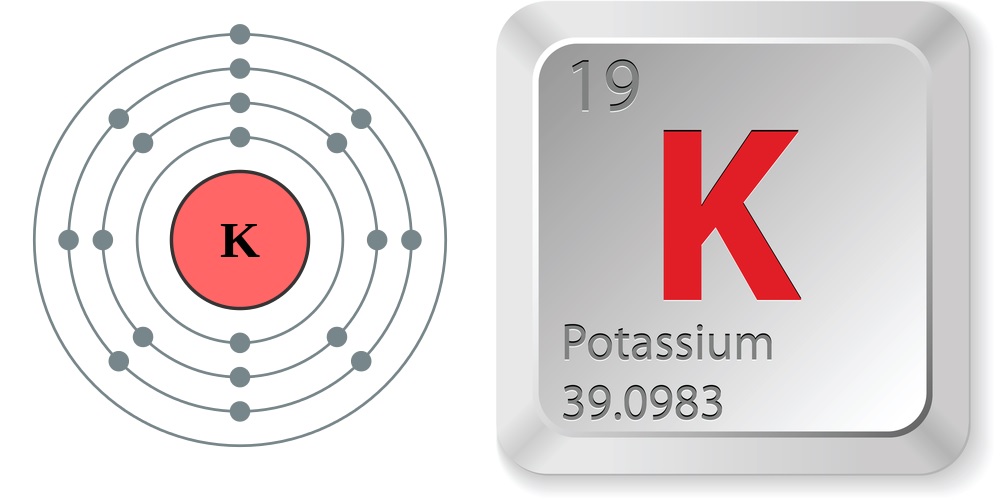

- Atomic number (number of protons in the nucleus): 19

- Atomic symbol (on the Periodic Table of Elements): K (from the Latin word for alkali, kalium.)

- Atomic weight (average mass of the atom): 39.0983

- Density: 0.89 grams per cubic centimeter

- Phase at room temperature: Solid

- Melting point: 146.08 degrees Fahrenheit (63.38 degrees Celsius)

- Boiling point: 1,398 degrees Fahrenheit (1,032 degrees Celsius)

- Number of isotopes (atoms of the same element with a different number of neutrons): 29; 3 naturally occuring

- Most common isotopes: K-39 (93.3 percent natural abundance), K-40 (0.0117 percent natural abundance), K-41 (6.73 percent natural abundance)

Common, and sometimes deadly

About 2.4 percent of the mass of Earth's crust is potassium, including billions of tons of potassium chloride, according to the Royal Society of Chemistry. It's not surprising that humans have made use of this resource. Saltpeter (potassium nitrate) was used to preserve food in the Middle Ages and is part of gunpowder, which was invented in ninth-century China. Potassium alum (KAI(SO4)2) might show up in your deodorant (it inhibits bacterial growth) or in textile and leather production. Potash, a generic term for any salt containing water-soluble potassium, is a major ingredient in fertilizers.

The word "potash" comes from "pot ash," harkening back to the original method of production of these salts. Plants are rich in potassium, so people would collect wood ash and leech out the potassium salts for use in fertilizer. In the modern day, potash is mined, with 35 million metric tons pulled from the Earth each year, according to the RSC.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Potassium is also a necessary nutrient for life; as an electrolyte, it conducts electric signals in the body; along with sodium, it's crucial for proper muscle contraction. The drug potassium chloride is commonly used to treat potassium deficiency, but the dose makes the poison: Potassium chloride has also been used in lethal injections. In large enough quantities, the drug stops the heart by disrupting the electrical signals that force the muscle to contract and relax, according to a 2012 case report in the journal Case Reports in Emergency Medicine.

Who knew?

- Low potassium in the body is called hypokalemia. Symptoms include muscle cramps, weakness and irregular heartbeat, according to the University of Maryland Medical Center. High potassium, called hyperkalemia, causes similar symptoms.

- Your potassium levels may be off without these extreme symptoms, however. A 2008 study published in the journal Hypertension found that certain blood pressure drugs can result in low potassium levels, which in turn raises the risk of Type 2 diabetes.

- Sounds fun: According to Humphry Davy's lab assistant, the scientist reacted with glee when he discovered his new element. "I have been told by Mr. Edmund Davy, his relative and assistant … that when he saw the minute globules of potassium burst through the crust of potash, and take fire as they entered the atmosphere [Humphry Davy] could not contain his joy — he actually danced about the room in ecstatic delight," John Davy wrote in his "Memoirs of the life of Sir Humphry Davy."

Current research

Potassium, along with its partner in crime, sodium, is crucial for maintaining blood pressure, among its others activities in the body. As such, the U.S. Department of Agriculture recommends that adults eat 4.7 grams of potassium a day, while the World Health Organization calls for a slightly lower intake of 3.5 grams.

Potassium doesn't get as much attention as sodium in the popular press, but it's extremely important, said Sylvia Wassertheil-Smoller, a professor emerita of epidemiology at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York. In September 2014, Wassertheil-Smoller and her colleagues found that a diet high in potassium was linked to fewer strokes in postmenopausal women. Overall, women who ate the most potassium in their diets were 12 percent less likely to have a stroke during the 11-year study period.

Notably, Wassertheil-Smoller told Live Science, potassium's protective effect "went beyond blood pressure." Women who did not have high blood pressure got a bigger health benefit from potassium than women with high blood pressure, the researchers reported in the journal Stroke. Among women with normal blood pressure, those who ate the most potassium were 21 percent less likely to have a stroke than those who ate the least.

"Potassium is involved in the health of cells and of blood vessels," Wassertheil-Smoller said. "We're not exactly sure of the mechanism, but there is something about potassium intake that does lower stroke risk."

Potassium is in a lot of foods, Wassertheil-Smoller said, most famously bananas. It's also in potatoes, leafy greens, salmon, apricots, squash, tomato paste and milk. But chances are you aren't reaching the recommended consumption of this nutrient.

A study released in the journal BMJ Open in 2015 found that only about 20 percent of Americans meet the WHO goals for potassium intake. Other countries didn't do much better: Only about 5 percent of Mexicans, 23 percent of people in France and 8 percent of Brits managed to eat enough potassium.

The data confirm that people don't get enough potassium for optimal health, said study researcher Adam Drewnowski, an epidemiologist at the University of Washington. On the other hand, the low rate of compliance with the recommendations suggests that the goals are unfeasible, Drewnowski said in a statement.

"The chances that a majority of a population would achieve these goals is near zero," he said.

Likewise, among the older women in Wassertheil-Smoller's study, only 2.8 percent met the USDA goals for potassium, and only 16.6 percent reached the WHO goals.

Part of the problem, according to Drewnowski, is that sodium and potassium are comingled in many foods, so attempts to cut sodium intake often cut potassium, too — only about 0.3 percent of Americans managed to meet both the sodium and potassium guidelines set by the WHO. (Scientists currently debate how much sodium intake affects blood pressure and heart health, or whether the sodium-potassium ratio is more important).

Public health officials need to work to get the word out about potassium, Wassertheil-Smoller said. A diet high in unprocessed foods, fruits and vegetables is typically a diet high in potassium, she said.

"The takeaway message is pay attention to which foods are rich in potassium, and eat them," she said.

Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Additional resources

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus