Da Vinci's Forgotten Design for the Longest Bridge in the World Proves What a Genius He Was

It would have been held together by compression only.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

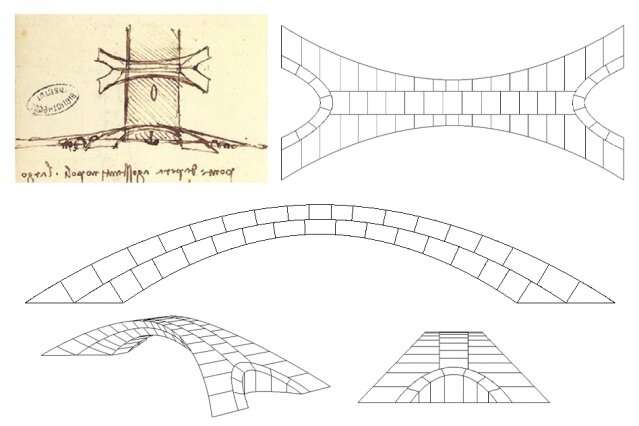

Leonardo da Vinci was truly a Renaissance man, impressing both his contemporaries and modern observers with his intricate designs that spanned many disciplines. But although he's best known for iconic works such as "Mona Lisa" and "Last Supper," in the early 16th century, da Vinci designed a lesser-known structure: a bridge for the Ottoman Empire that would have been the longest bridge of its time. Had it been built, the bridge would have been incredibly sturdy, according to a new study.

In 1502, Ottomon ruler Sultan Bayezid II requested proposals for the design of a bridge that would connect Constantinople, what's today Istanbul, to the neighboring area known as Galata. Da Vinci was among those who sent a letter to the sultan describing a bridge idea.

Though da Vinci was already a well-known artist and inventor, he didn't get the job, according to a statement from MIT. Now, a group of researchers at MIT has analyzed da Vinci's design and tested how robust his bridge would have been if it were built.

Related: Leonardo Da Vinci's 10 Best Ideas

The group built a replica of the bridge, after taking into consideration the materials and construction equipment available 500 years ago and the geological conditions of the Golden Horn, a freshwater estuary in the Bosphorus Sea over which the bridge would've been built.

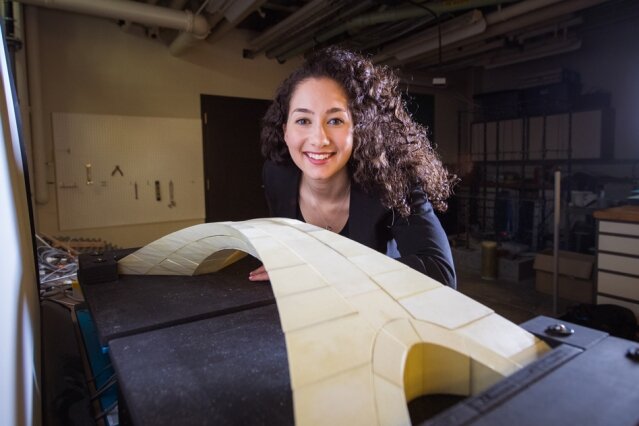

In his descriptions, da Vinci didn't indicate the materials or equipment needed to construct the bridge, but the only material available at the time, that wouldn't have collapsed under large loads on such a long bridge, would have been stone, Karly Bast, a recent graduate student at MIT who worked on the project, and her team found. The researchers also hypothesized that such a bridge would have stood on its own without any paste or material to hold the stone together.

To test the sturdiness of the bridge, the team 3D printed 126 blocks to represent the thousands of stone blocks the original bridge would have required. Their model was 500 times smaller than da Vinci's bridge design, which would have extended about 919 feet (280 meters).

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Though the da Vinci bridge would have been nearly four times shorter than the modern George Washington Bridge and 4.5 times shorter than the Golden Gate Bridge, it would have been the longest of its time, according to the statement. "It's incredibly ambitious," Bast said in the statement. "It was about 10 times longer than typical bridges of that time."

What's more, most bridge supports at the time were designed as a semicircular arch and would have required 10 or more piers to support that length of bridge, according to the statement. But da Vinci's design was a single arch, flattened at the top, that would have been tall enough to allow sailboats to pass underneath.

The researchers put together the 3D-printed blocks using a scaffold, but once they put the "keystone" at the top of the arch, they removed the scaffold, and the bridge kept standing. "It's the power of geometry"; the bridge held together by compression only, she said.

Da Vinci's design and the MIT scientists' model also included structures called abutments that extended outward on both sides of the ends of the bridge to stabilize it against side-to-side movements, likely because da Vinci knew the region was prone to earthquakes. Bast and her team built the bridge on two moving platforms. They stimulated what would happen when one platform moved away from the other, as can happen over time when heavy structures are built on weak soil. The bridge was resilient against the movement, though it deformed slightly after being stretched a lot.

"Was this sketch just freehanded, something he did in 50 seconds, or is it something he really sat down and thought deeply about? It's difficult to know," Bast said. But this testing of da Vinci's design suggests that he spent some time carefully thinking about it, she added.

The group presented the results at the International Association for Shell and Spatial Structures conference in Barcelona, Spain, this week. Their research has yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal.

- 5 Things You Probably Didn't Know About Leonardo da Vinci

- Flying Machines? 5 Da Vinci Designs That Were Ahead of Their Time

- In Photos: Leonardo Da Vinci's 'Mona Lisa'

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus