Shroud of Turin wasn't laid on Jesus' body, but rather a sculpture, modeling study suggests

A 3D analysis comparing the way fabric falls on a human body versus a low-relief sculpture shows that the Shroud of Turin was not based on a real person.

The Shroud of Turin, famously claimed to be Jesus' original burial covering, could not have been created on a three-dimensional human body, a new study finds. It is much more likely that the image is an imprint of a low-relief sculpture, according to a graphics expert.

In a study published Monday (July 28) in the journal Archaeometry, Brazilian 3D digital designer Cicero Moraes, who specializes in historical facial reconstructions, used modeling software to compare how cloth drapes over a human body versus how it drapes over a low-relief sculpture of one.

"The image on the Shroud of Turin is more consistent with a low-relief matrix," Moraes told Live Science in an email. "Such a matrix could have been made of wood, stone or metal and pigmented (or even heated) only in the areas of contact, producing the observed pattern," he said.

The shroud was first recorded in the late 14th century, and controversy over whether it was an authentic relic from the crucifixion and death of Jesus kicked off immediately. A carbon dating analysis carried out in 1989 placed the shroud's creation in the range A.D. 1260 to 1390, solidifying its interpretation as a medieval artifact.

During this time in European medieval history, low-relief depictions of religious figures — such as carved tombstones — were widely used, previous art historical analysis has found.

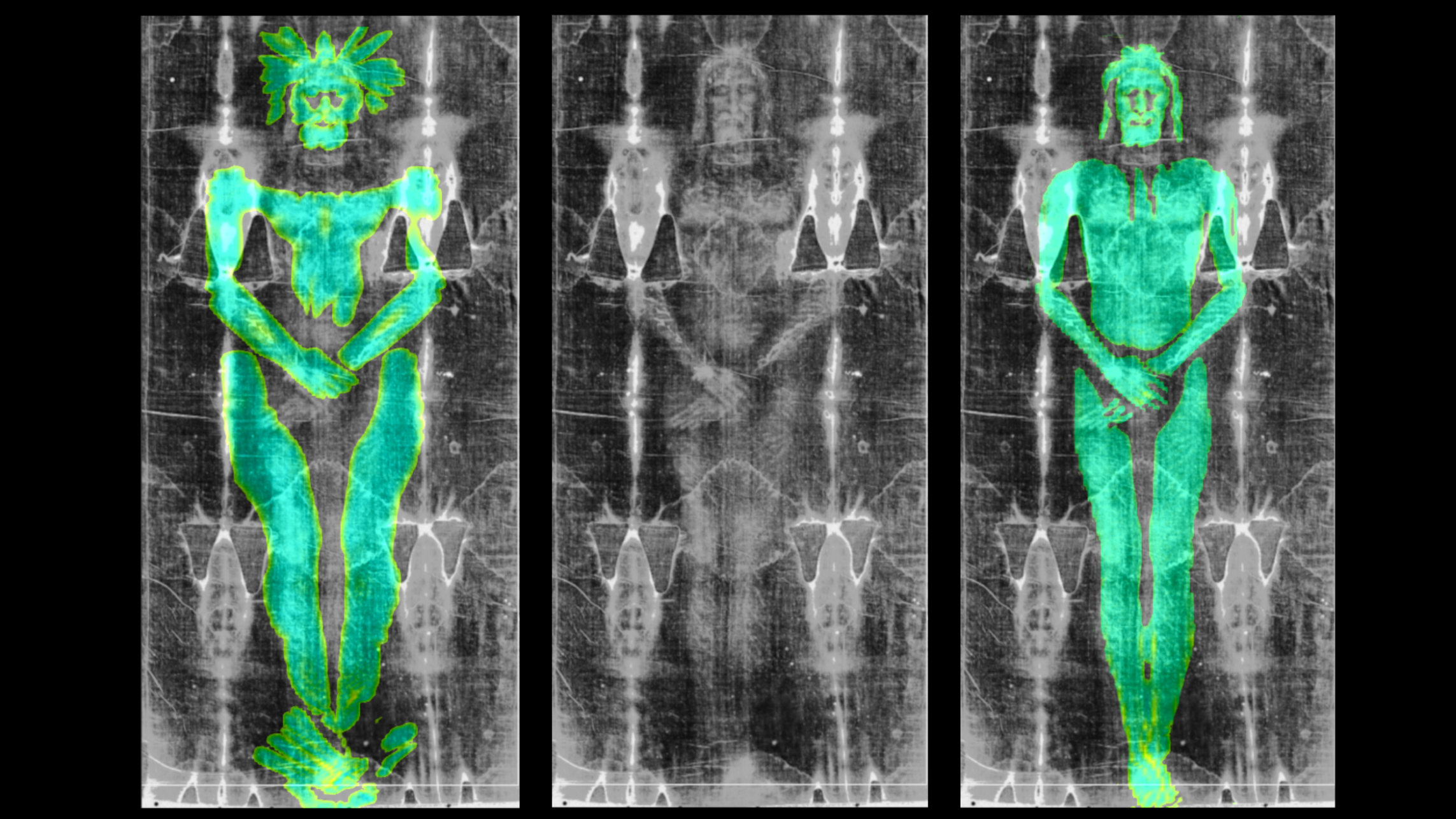

To investigate how the Shroud of Turin might have been made, Moraes created and analyzed two digital models. The first model represented a three-dimensional human body, and the second model was a low-relief representation of a human body.

Using 3D simulation tools, Moraes then virtually draped fabric onto the two different body models. When he compared the virtual fabric to photographs of the shroud taken in 1931, Moraes found that the fabric from the low-relief model almost exactly matched the photographs.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Related: Is it a fake? DNA testing deepens mystery of Shroud of Turin

In the simulation with the three-dimensional body, Moraes wrote in the study, the fabric deformed around the volume of the body, resulting in a swollen and distorted image. This distortion is sometimes called the "Agamemnon Mask effect," he wrote, after the unnaturally wide gold death mask found in a tomb at Mycenae in Greece.

Moraes demonstrated in a video how the Agamemnon Mask effect works by painting his face and pressing a paper towel to it. The resulting image is much wider than a front view of his face due to the distortion caused by imprinting a 3D object onto a 2D piece of fabric.

But a low-relief sculpture wouldn't cause the image to deform and would look more like a photocopy, similar to the Shroud of Turin, Moraes said, because it shows only the regions of potential direct contact, without any real volume or depth.

Rather than assuming the Shroud of Turin was the result of draping fabric on a human body, Moraes favors the explanation that it was created within a funerary context, making it "a masterpiece of Christian art." Moraes did not investigate the methods or materials that may have been used to make the shroud, however.

Although there is a "remote possibility that it is an imprint of a three-dimensional human body," Moraes wrote, "it is plausible to consider that artists or sculptors with sufficient knowledge could have created such a piece, either through painting or low relief."

One expert thinks that Moraes is right but that his study is not particularly groundbreaking.

"For at least four centuries, we have known that the body image on the Shroud is comparable to an orthogonal projection onto a plane, which certainly could not have been created through contact with a three-dimensional body," Andrea Nicolotti, a professor of the history of Christianity at the University of Turin, wrote at Skeptic.

"Moraes has certainly created some beautiful images with the help of software," Nicolotti wrote, "but he certainly did not uncover anything that we did not already know."

Moraes suggests that his method is accessible and replicable, and that his work "highlights the potential of digital technologies to address or unravel historical mysteries" by bringing together science, art and technology.

What do you know about Jesus Christ, the man? Test your knowledge of biblical archaeology

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Kristina holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology and an M.A. in classical archaeology from the University of North Carolina, as well as a B.A. in Latin from the University of Virginia, and she was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus