Drought Exacerbates Carbon Dioxide Problem

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

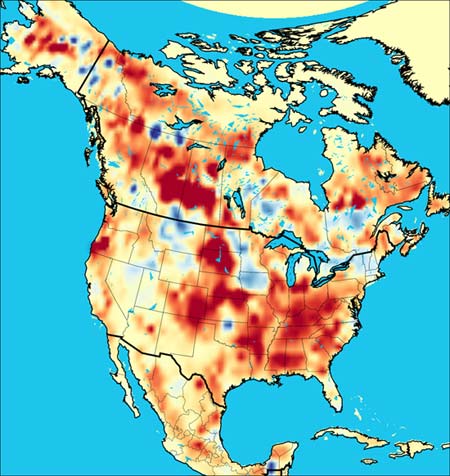

Droughts do more harm than just parching the land. They can also exacerbate rising carbon dioxide levels, government scientists have found.

In North America alone, human activity—from driving cars to generating power in factories—releases about two billion tons (1.85 billion metric tons) of carbon in the form of carbon dioxide every year. Natural carbon sinks such as forests, grasslands, crops and soil absorb about one-third of those emissions, scientists estimate.

But droughts seem to hamper the ability of these sinks to suck up the greenhouse gas. A new measurement system introduced by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, called CarbonTracker, has provided scientists with weekly observations of carbon dioxide exchange from 2000 to 2005.

The data, detailed in a new study in the Nov. 26 issue of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, showed that in 2002, when North America experienced one of the largest droughts in more than a century, the amount of carbon taken up by vegetation and soil plunged from 716 million tons to 363 million tons.

"Scientists often look at the role of greenhouse gases in producing climate extremes," said study leader Wouter Peters, affiliated with Wageninen University and Research Center in The Netherlands. "Here we show the reverse is also true. Climate extremes can have a major effect on the amount of carbon dioxide in Earth’s atmosphere."

Drought and other variations in a region's climate can change temperatures, rainfall, soil moisture and even the length of the growing season in that region. If less rain falls and soil moisture drops, plants may wither and die and so take up less carbon dioxide.

The connection between drought and increased carbon dioxide levels isn't unique to North America; the widespread drought and heat wave that struck Europe in 2003 left more than 500 million extra tons of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere that year, CarbonTracker showed. This problem could have consequences for efforts aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Disruptions to natural carbon uptake can have enormous environmental and economic effects, possibly even erasing efforts to reduce fossil fuel emissions in a given year," Peters said.

- Top 10 Natural Disasters

- Man vs. Nature and the New Meaning of Drought

- Timeline: The Frightening Future of Earth

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus