Neanderthals Likely Built These 176,000-Year-Old Underground Ring Structures

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

About 40,000 years before the appearance of modern man in Europe, Neanderthals in southwestern France were venturing deep into the earth, building some of the earliest complex structures and using fire.

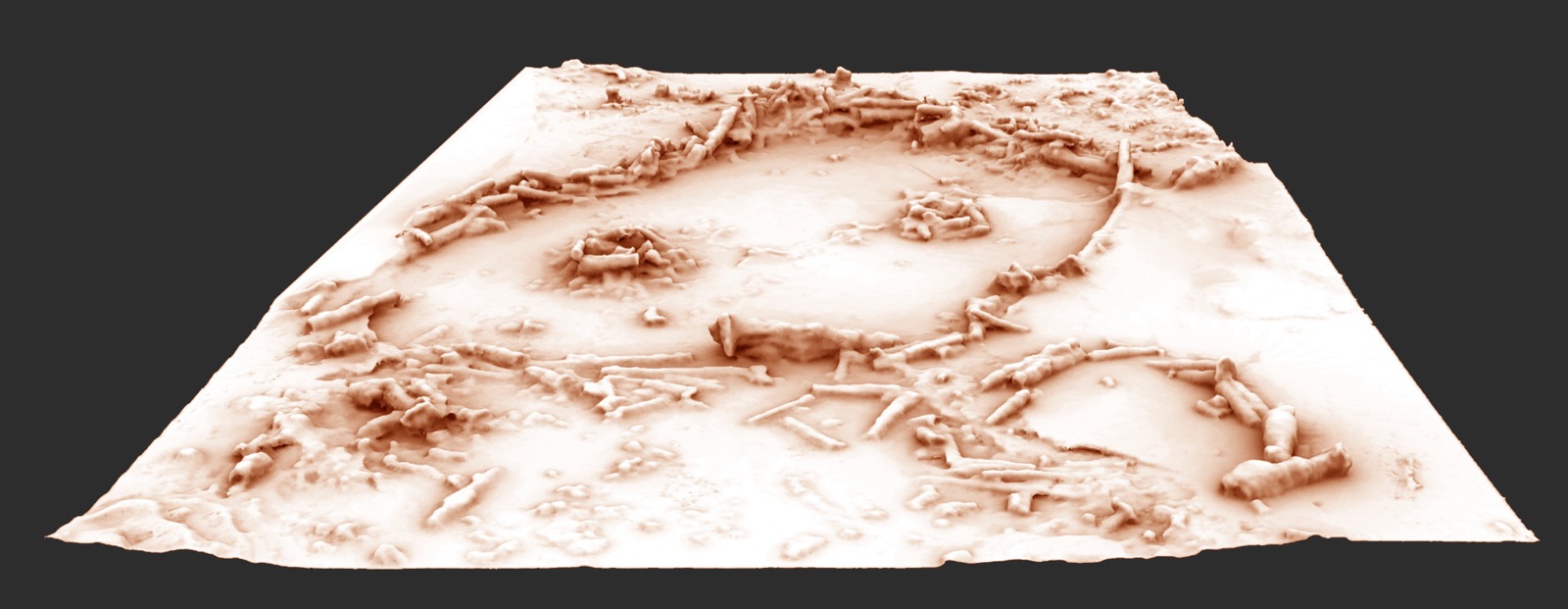

That's according to new research that more precisely dated bizarre cave structures built from stalagmites, or mineral formations that grow upward from the floor of a cave. Scientists discovered about 400 stalagmites and stalagmite sections that were collected and stacked into nearly circular formations about 1,100 feet (336 meters) from the entrance of Bruniquel Cave, which was discovered in 1990.

Dating these formations to a time when Neanderthals, but not modern humans, were present in Eurasia, makes the finding the oldest directly dated constructions attributed to Neanderthals, according to Marie Soressi, an archaeologist at Leiden University in the Netherlands, who wrote a News and Views article in the same issue of the journal Nature in which the original study is published. [See Photos of the Bizarre Ring-Like Structures in Bruniquel Cave]

Dating bone

Soot stains, heat fractures and burnt material, including bone, point to the likelihood that these circles were used to contain fires back in the day.

In 1995, some of the burnt bone was dated using carbon-14 dating, a technique that measures the ratio of carbon-14 to carbon-12; that ratio indicates about how long an organism has been dead. It was found to be 47,600 years old — the maximum age carbon-14 dating can attain.

More recently, lead author Jacques Jaubert, of the University of Bordeaux in France, and his colleagues revisited this site, with more advanced surveying and dating technology. Through a technique called uranium-series dating, which relies on the breakdown of uranium to thorium, they were able to estimate when the stalagmites were broken and moved into the circular formations. They found the installations are approximately 176,500 years old (give or take 2,000 years).

Human-made structures

These structures are "among the oldest known well-dated constructions made by humans," Jaubert and his colleagues wrote in their research paper published yesterday (May 26) in the journal Nature.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Evidence of a human-made structure exists in Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, dated at over 1 million years old. But this has not been studied extensively, Jaubert said. He added there is similarly little information about a Homo erectus campsite in Bilzingsleben, Germany (about 400,000 years old), early shelters in Terra Amata, France (about 400,000 years old), and the bone and stone materials found in France's Lazaret cave (around 170,000 years old). Researchers have credited Neanderthals with making a building out of mammoth bone in Ukraine. They believe this is about 40,000 years old.

"In any case, there are many examples of concentrations [of] remains, hearths, lithic [stone] workshops, faunal structures … but never the structures of this magnitude. And in this deep cave context!" Jaubert wrote in an email to Live Science. Before the Bruniquel Cave discovery, the cave paintings of Chauvet, France, were the oldest evidence of cave use by humans or human ancestors. Those date back a mere 38,000 years. [In Photos: The World's Oldest Cave Art]

The amazing Bruniquel Cave

The Bruniquel Cave is located on private property, overlooking the Aveyron Valley, near a tributary of the Tarn. This area is rich in Paleolithic sites (dated to about 2.6 million to 10,000 years ago). Near the entrance is another important paleontological site of a similar age or potentially older, Jaubert said. The cave has a narrow entrance and is 33 to 49 feet (10 to 15 meters) wide, 13 to 23 feet (4 to 7 m) high, and — as far as anyone knows — 1,581 feet (482 m) long.

When the cave was first discovered, speleologists (people who study caves) meticulously preserved its natural formations, which aside from the stalagmite circles, include translucent flowstone, an underground lake and calcite rafts, or thin sheets of calcite that formed on the surface of the lake. Calcite is a rock-forming mineral found in limestone and marble. The speleologists also took care to keep Bruniquel's bone remains and dozens of bear hibernation hollows in pristine condition. A thick layer of calcite had coated all the structures, making dating techniques difficult to perform. [In Photos: One-of-a-Kind Places on Earth]

For the next two decades, very few people visited the cave, Jaubert said. He thinks part of this may have been due to the death of the original researcher, archaeologist Francois Rouzaud. Additionally, he said the cave is challenging to access, not only physically but also because it is on private property and there are many conditions that need to be met in order for the owners and the French Ministry of Culture to authorize new research.

In 2013, using 3D-surveying equipment and magnetic measurements that record anomalies caused by heat, researchers were able to map both the stalagmite structures and the burnt remnants. Stalagmite arrangements of this scale are unprecedented, so the research team created the term "speleofacts" to describe each piece of stalagmite used in the structures. They estimate there were about 400 speleofacts total, with a combined weight of between 2.3 and 2.6 tons (2.1 and 2.3 metric tonnes) and a combined length of 367 feet (112 m). Jaubert said the stalagmites were the only raw material available for building in the cave.

Social Neanderthals

Until now, Neanderthals were "presumed by the scientific community not to have ventured far underground, nor to have mastered such sophisticated use of lighting and fire, let alone to have built such elaborate constructions," according to a statement by the National Center for Scientific Research.

"This type of construction implies the beginnings of a social organization: This organization could consist of a project that was designed and discussed by one or several individuals, a distribution of the tasks of choosing, collecting and calibrating the speleofacts, followed by their transport (or vice versa) and placement according to a predetermined plan," wrote the researchers in the Naturearticle. The researchers also said this process would have required adequate lighting and determined that the fires in the cave were likely used as light sources.

Given their distance from the cave entrance and daylight, the team said it was unlikely the circles were used as shelters. They didn't rule out the possibility that they could have been used for technical purposes, such as water storage, or religious or ceremonial purposes. Jaubert said the next steps in studying the cave will include further examination of the structures, a more extensive survey of the cave's interior to uncover any additional archaeological remains, and a closer look at the cave's entrance.

The find has added extensively to scientists' knowledge of Neanderthal social organization and human cave dwelling in prehistory, the researchers said. Even so, they added, the question remains: What were the structures used for?

Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus