Paleo-Inuit people braved icy seas to reach remote Greenland islands 4,500 years ago, archaeologists discover

Archaeological remains on the Kitsissut islands off the coast of Greenland reveal that whole communities regularly journeyed across the dangerous Arctic waters.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Paleo-Inuit people reached remote islands in the High Arctic off the northwest coast of Greenland nearly 4,500 years ago, according to a new study that documents evidence of prehistoric dwellings there.

These early Arctic people, who had fine-tuned advanced watercraft technology and seafaring skills, repeatedly made the treacherous open-water journey to the islands to access vital maritime resources.

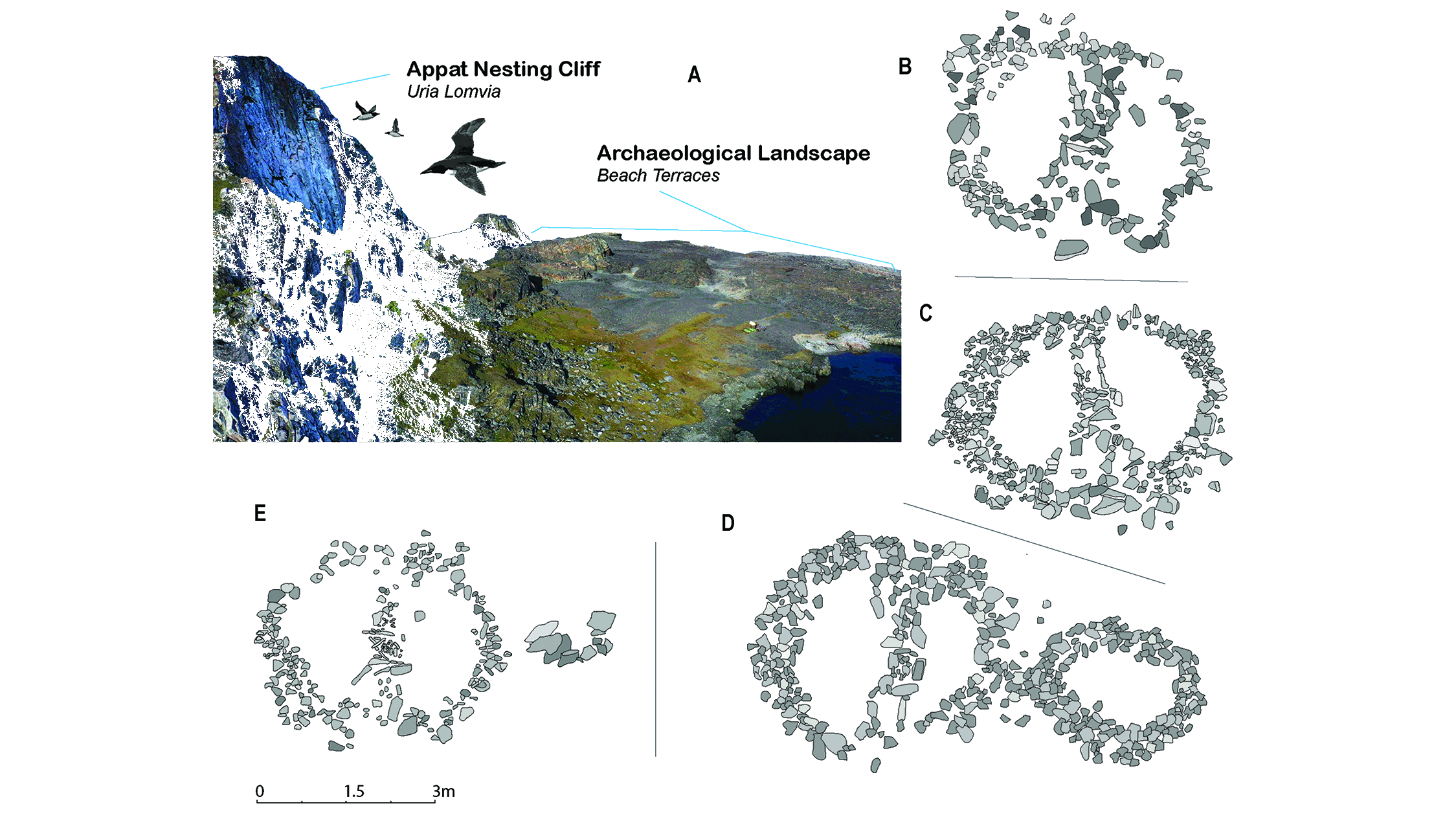

The island cluster of Kitsissut (also known as the Carey Islands) is the westernmost point of Greenland. Consisting of six small islands, Kitsissut is located at the heart of a rich marine environment called a polynya, which is a semipermanent area of open water in the middle of sea ice. Contemporary Inuit identified Kitsissut as an important place for hunting seabirds and accessing eggs, which prompted a team of archaeologists to investigate the islands for traces of prehistoric activity.

Article continues belowIn a study published Monday (Feb. 9) in the journal Antiquity, researchers detailed the results of their archaeological survey of three of the islands. They found nearly 300 archaeological features in their survey, with the largest concentration being 15 Paleo-Inuit dwellings at the tip of Isbjørne Island. The dwellings suggested that people made the difficult journey from Greenland's mainland to Kitsissut numerous times.

The dwellings were identified by a ring of stones indicating the past presence of a tent with a hearth at the center. Based on an animal bone discovered in one of the tent rings, the archaeologists dated the occupation to around 4,000 to 4,475 years ago.

"In a regional perspective, it is a lot of tent rings in one place, indeed one of the largest concentrations," study lead author Matthew Walls, an archaeologist at the University of Calgary in Canada, told Live Science in an email. This suggests that Kitsissut and the polynya was "a place of return," Walls said. "It wasn't just a one-off visit by a family blown off course, for example."

It is unclear exactly how the Paleo-Inuit people arrived at Kitsissut, but the minimum journey from the mainland to the dwellings on Isbjørne Island is 33 miles (53 kilometers), the researchers wrote in the study. The route through the open sea is marked by erratic crosswinds, dense fog and powerful mixing currents — an extraordinarily risky journey that would have taken around 12 hours to complete in a wood-framed, skin-covered watercraft typical of Paleo-Inuit peoples.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"They are almost certainly visiting during the warm season, which doesn't last very long," Walls said. "The travel conditions also make it most likely that they are doing this in the brief summer."

Paleo-Inuit people probably headed to Kitsissut to hunt and gather eggs from the thick-billed murre (Uria lomvia), a polar seabird that nests in the thousands in the summer. The dwelling sites the archaeologists found are located directly below their nesting cliffs, Walls said, and there are numerous murre bones around the tent rings.

"The number of rings does give the sense that it is a whole community making the crossing, rather than a small hunting party," Walls said, but "that is something that we could perhaps prove with further excavation, giving us a better snapshot of community life."

The Paleo-Inuit people's ability to navigate frigid expanses of open water in kayak-like vessels to reach Kitsissut shows their strong commitment to a maritime lifestyle, the researchers wrote, but it also demonstrates their advanced skills in navigation and watercraft technology.

"Archaeologists have tended to think about the area as a crossroads, or primarily a route of movement between Canada and Greenland," Walls said. But Kitsissut and the polynya are "better framed as a place of innovation."

Walls, M., Kleist, M., & Knudsen, P. (2026). Voyage to Kitsissut: a new perspective on Early Paleo-Inuit watercraft and maritime lifeways at a High Arctic polynya. Antiquity. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2026.10285

Archaeology Fragments Quiz: Can you work out what these mysterious artifacts are?

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Kristina holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology and an M.A. in classical archaeology from the University of North Carolina, as well as a B.A. in Latin from the University of Virginia, and she was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus