World's oldest known sewn clothing may be stitched pieces of ice age hide unearthed in Oregon cave

The sewn hide, cordage and needles show how Indigenous Americans used complex technology to survive the freezing temperatures at the end of the last ice age and as a means of social expression.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The oldest known sewn clothing in the world may be pieces of animal hide that Indigenous people stitched together with plant and animal cords and then left in an Oregon cave around 12,000 years ago, during the last ice age, a new study finds.

Although its exact use is unknown, the sewn hide is "quite possibly a fragment of clothing or footwear," which would represent the only known item of clothing recovered from the Pleistocene to date, the researchers wrote in the study, which was published Feb. 4 in the journal Science Advances.

An amateur archaeologist discovered the sewn hides in 1958, but the new study is the first to date the artifacts. In their paper, the team determined that 55 pieces of crafted animal and plant materials previously unearthed in two Oregon caves — including sewn hide, cords and twine — stemmed from the Younger Dryas, a period of sudden cooling that occurred from about 12,900 to 11,700 years ago.

Article continues belowThe discovery provides clear evidence that Indigenous people in North America shielded themselves from the worst of the cold by using complex technology made from perishable materials. Sewing pieces of hide together allowed for tight-fitting clothing, which would have provided more warmth than simple, loose-fitting draped hide clothes.

"We already knew they did, we just had to assume and guess what they were like," study lead author Richard Rosencrance, a doctoral researcher in anthropology at the University of Nevada, Reno, told Live Science in an email. "They were accomplished and serious sewists during the Ice Age."

Clothes, along with other technologies required to keep people warm, were essential for permanent residence in northern latitudes, including areas of North America. But exactly when humans began to wear clothes is unknown, and the perishable nature of the materials means they are rarely found.

To date, there are only four sites — all in Oregon and Nevada — where non-bone animal and plant technology from the Late Pleistocene has been discovered in the Western Hemisphere. (The Late Pleistocene spanned 126,000 to 11,700 years ago and includes the last ice age.)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Archaeologists previously discovered two of the largest collections of Late Pleistocene perishable tools in the world in Cougar Mountain Cave and the Paisley Caves in Oregon, according to the new study. These artifacts included 37 fiber cords, baskets and knots; 15 wooden implements; and three sewn hides.

Rosencrance and his team used radiocarbon dating to determine the ages of these artifacts and confirmed that all of them date to the Younger Dryas. The cords were braided using three strands and were made using sagebrush, dogbane, juniper and bitterbrush fibers. Because the cords varied from 0.13 to 1 inch (0.33 to 2.5 centimeters) wide, they were probably used for a range of purposes, the researchers wrote in the study.

The three pieces of animal hide had been processed and dehaired, with cord made from a combination of plant fiber and animal hair sewn into the sides. The sewn hide dates to between 12,676 and 11,956 years ago, and an analysis of the chemical makeup of the animal hides revealed they came from North American elk (Cervus canadensis). (The oldest known shoes in the world are also from a cave in Oregon, and they date to about 10,400 years ago.)

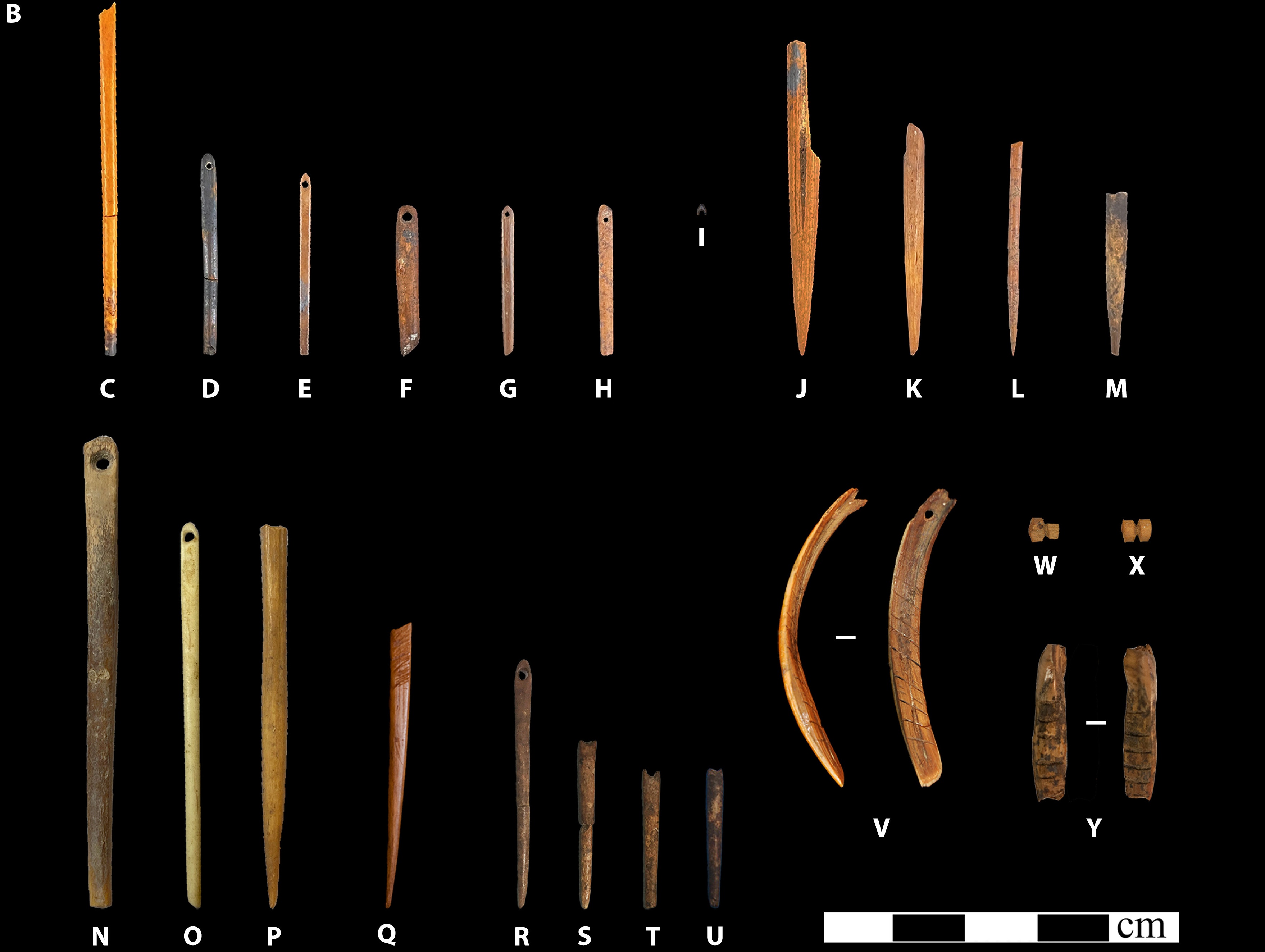

The authors of the new study also examined 14 eyed and three eyeless bone needles that had previously been discovered at Cougar Mountain Cave and the Paisley Caves, as well as the nearby Connley Caves and Tule Lake Rockshelter. In addition, they looked at four potential ornamental items uncovered in the Connley Caves, including a porcupine tooth with a hole drilled into the top and lines scratched onto the surface.

"The abundance of bone needles and the presence of adornment items and very fine-eyed needles suggest that clothing was more than a utilitarian survival strategy but also an avenue of expression and identity," the authors wrote. "This evidence pushes beyond conventional assumptions to confirm that Pleistocene peoples in the Americas used clothing as both survival technology and social practice."

Eyed bone needles disappeared from the archaeological record in Oregon after around 11,700 years ago, Rosencrance said, which suggests that tight-fitting clothing became less important as the climate warmed.

Editor's Note: This story was updated on March 5 at 9:29 a.m. ET to correct the date range of the sewn hide. The radiocarbon dates were 12,600 to 11,880 before present (BP), calibrated to 1950, meaning the hide is 12,676 to 11,956 years old.

Rosencrance, R. L., Smith, G. M., McDonough, K. N., Jazwa, C. S., Antonosyan, M., Kallenbach, E. A., Connolly, T. J., Culleton, B. J., Puseman, K., McGuinness, M., Jenkins, D. L., Stueber, D. O., Endzweig, P. E., & Roberts, P. (2026). Complex perishable technologies from the North American Great Basin reveal specialized Late Pleistocene adaptations. Science Advances, 12(6), eaec2916. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aec2916

Sophie is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She covers a wide range of topics, having previously reported on research spanning from bonobo communication to the first water in the universe. Her work has also appeared in outlets including New Scientist, The Observer and BBC Wildlife, and she was shortlisted for the Association of British Science Writers' 2025 "Newcomer of the Year" award for her freelance work at New Scientist. Before becoming a science journalist, she completed a doctorate in evolutionary anthropology from the University of Oxford, where she spent four years looking at why some chimps are better at using tools than others.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus