Aquifers: Underground Stores of Freshwater

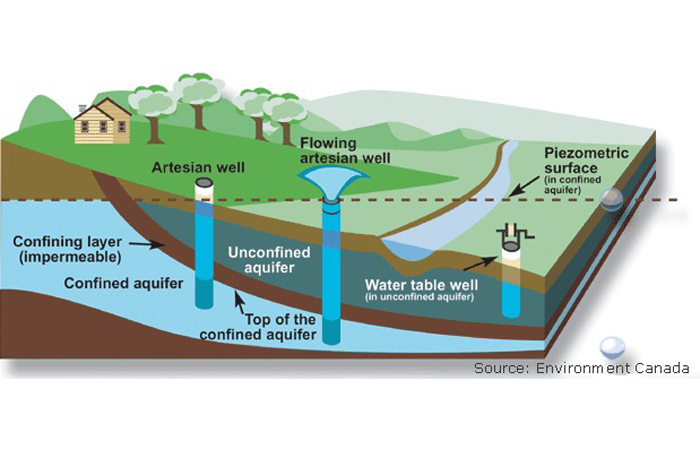

Aquifers are underground layers of rock that are saturated with water that can be brought to the surface through natural springs or by pumping.

The groundwater contained in aquifers is one of the most important sources of water on Earth: About 30 percent of our liquid freshwater is groundwater, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The rest is found at the surface in streams, lakes, rivers and wetlands. Most of the world's freshwater — about 69 percent — is locked away in glaciers and ice caps. The U.S. Geological Survey website has a map of important aquifers in the contiguous United States.

Groundwater can be found in a range of different types of rock, but the most productive aquifers are found in porous, permeable rock such as sandstone, or the open cavities and caves of limestone aquifers. Groundwater moves more readily through these materials, which allows for faster pumping and other methods of extracting the water. Aquifers can also be found in regions where the rock is made of denser material — such as granite or basalt — if that rock has cracks and fractures.

"Aquifers come in many shapes and sizes, but they are really a contained, underground repository of water," said Steven Phillips, a hydrologist with the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) in Sacramento, California.

Dense, impermeable material like clay or shale can act as an "aquitard," i.e., a layer of rock or other material that is almost impenetrable to water. Through groundwater might move through such material, it will do so very slowly (if at all). Faults or mountains can also block the movement of fresh groundwater, as can the ocean, Phillips said.

An aquitard can trap groundwater in an aquifer and create an artesian well. When groundwater flows beneath an aquitard from a higher elevation area to a lower elevation, such as from a mountain slope to a valley floor, the pressure on the groundwater can be enough to force the water out of any well that's drilled into that aquifer. Such wells are known as artesian wells, and the aquifers they tap into are called artesian aquifers or confined aquifers.

How groundwater moves

When new surface water enters an aquifer, it "recharges" the groundwater supply. Recharge primarily happens near mountains, and groundwater usually flows downward from mountain slopes toward streams and rivers by the force of gravity, Phillips said. Depending on the density of the rock and soil through which groundwater moves, it can creep along as slowly as a few centimeters in a century, according to Environment Canada. In other areas, where the rock and soil are looser and more permeable, groundwater can move several feet in a day.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The water in an aquifer can be held beneath the Earth's surface for many centuries: Hydrologists estimate that the water in some aquifers is more than 10,000 years old (meaning that it fell to the Earth's surface as rain or snow roughly 6,000 years before Egypt's Great Pyramid of Giza was built). The oldest groundwater ever found was discovered 2 miles (2.4 km) deep in a Canadian mine and trapped there between 1.5 and 2.64 billion years ago.

But the deeper one digs for water, the saltier the liquid becomes, Phillips said. "Groundwater can be very, very deep, but eventually it's a brine," he said. "For freshwater, the depths are very limited."

Much of the drinking water on which society depends is contained in shallow aquifers. For example, the Ogallala Aquifer — a vast, 174,000 square-mile (450,000 square kilometers) groundwater reservoir — supplies almost one-third of America's agricultural groundwater, and more than 1.8 million people rely on the Ogallala Aquifer for their drinking water.

Similarly, Texas gets almost 60 percent of its water from groundwater; in Florida, groundwater supplies more than 90 percent of the state's freshwater. But these important sources of freshwater are increasingly endangered.

Threats to aquifers

By 2010, about 30 percent of the Ogallala Aquifer's groundwater had been tapped, according to a 2013 study from Kansas State University. Some parts of the Ogallala Aquifer are now dry, and the water table has declined more than 300 feet in other areas. More than two-thirds of this Ogalalla aquifer groundwater could be drained in the next several decades, the study found.

"The water levels have just been going down, down, down," Phillip said. "A lot of that system was recharged 10,000 years ago during the most recent glacial period, and what we're doing now is mining the water. We're taking out old water that isn't being replenished."

The same problem is increasingly found throughout the world, especially in areas where a rapidly growing population is placing greater demand on limited aquifer resources — pumping can, in these places, exceed the aquifer's ability to recharge its groundwater supplies.

When pumping of groundwater results in a lowering of the water table, then the water table can drop so low that it's below the depth of a well. In those cases, the well "runs dry" and no water can be removed until the groundwater is recharged — which, in some cases, can take hundreds or thousands of years.

When the ground sinks because of groundwater pumping, it is called subsidence. In California's southern San Joaquin Valley, where farmers rely on wells for irrigation, the land surface settled 28 feet (8.5 meters) between the 1920s and the 1970s, according to NASA, which uses satellite data to track subsidence.

"Land subsidence is a threat to aquifers and also to infrastructure on the surface," Phillips said.

In addition to groundwater levels, the quality of water in an aquifer can be threatened by saltwater intrusion (a particular problem in coastal areas), biological contaminants such as manure or septic tank discharge, and industrial chemicals such as pesticides or petroleum products. And once an aquifer is contaminated, it's notoriously difficult to remediate.

Additional resources:

- The U.S. Water Monitor is a daily "water health" report that summarizes federal water information.

- The USGS provides information on water quality in U.S. aquifers.

- The USGS National Water Information System's interactive map of nationwide water data.

This article was updated on Oct. 17, 2018 by Live Science Associate Editor, Tia Ghose.