Why Is Hurricane Sandy So Big?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

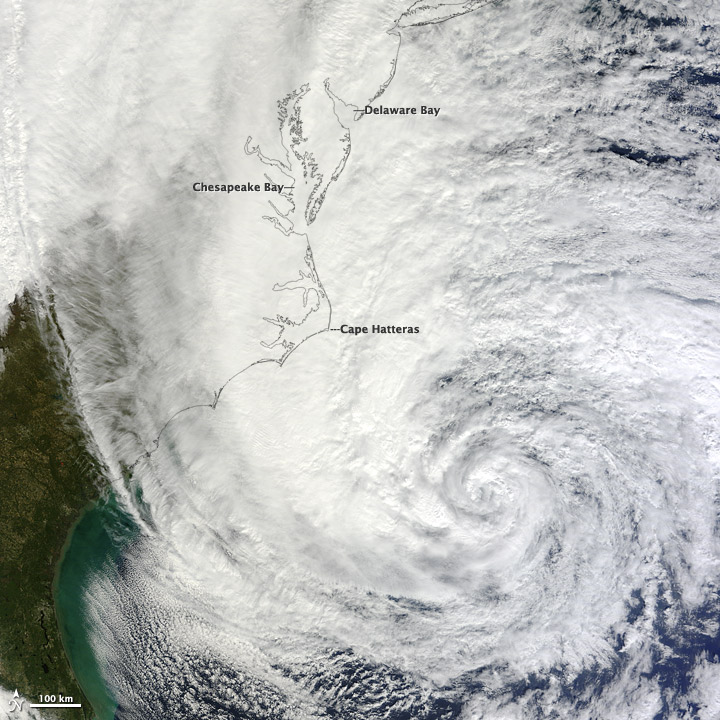

By tomorrow night (Oct. 29) or Tuesday, winds and clouds from Hurricane Sandy could stretch across the eastern third of the United States, according to weather predictions from the National Hurricane Center (NHC).

Sandy currently has hurricane-force winds extending up to 175 miles (280 kilometers) from its center, and tropical storm-force winds out to 520 miles (835 km), according to the NHC. That's second only to 2001's Olga in terms of the size of wind field of a storm. (Olga's winds extended out 600 miles (965 kilometers).

How did this Frankenstorm get so big?

Tropical transition

The main reason is that Sandy is morphing from a tropical cyclone to an extra-tropical cyclone, said Chris Davis, a scientist with the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colo. Extra-tropical cyclones, or those outside the tropics, tend to be significantly larger than tropical ones. Although Sandy is huge, its size is not unprecedented, he said. What's more unusual is the location and timing—nor'easters can get this big, but usually occur in the winter, he said.

Hurricane Sandy began as a tropical cyclone, fueled by warm water, warm, moist air and the convection these phenomena can create, Davis told OurAmazingPlanet. These hurricanes can be likened to heat engines, transferring heat from the surface of the ocean to higher in the atmosphere. By contrast, extra-tropical cyclones are driven by a difference in temperatures over a wide area— cold air to the northwest, warm air to the southeast, which then swirls together, Davis said. This process is most efficient over huge distances, said.

Sandy is progressing into an extra-tropical cyclone as it gets farther north, and tapping into the power of the jet stream, which ferries air from west to east over North America. The jet stream, like the storm itself, is powered by this temperature difference between air masses, he said. [4 Things You Need to Know About Hurricane Sandy]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Hurricane origins

While Sandy still retains the warm core of a tropical hurricane, it's also deriving power from the movement of warm air to the north and cold air to the south, similar in some respects to the Perfect Storm of 1991.

"It's an interesting case where both these processes are going on," Davis said.

Sandy started out as a large hurricane, but not unusually large. Although it's still unclear exactly what determines the size of hurricanes, it partially has to do with the amount of moist air found in the location where the cyclone is born, he said. In Sandy's case, there was ample warm, moist air in the western Caribbean, allowing it to become big.

"As a whole, we (the tropical storms community) don't know a lot about what controls tropical storm size," wrote Clark Evans, a scientist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, in an email. "We know that storms that form from smaller disturbances tend to be smaller; we also know that storms that form in drier environments tend to be smaller."

Reach Douglas Main at dmain@techmedianetwork.com. Follow him on Twitter @Douglas_Main. Follow OurAmazingPlanet on Twitter @OAPlanet. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus