'Now is the time': Hurricane category 6 could be introduced under new storm severity scale

The current hurricane classification does not consider storm surge and rainfall risks, which cause almost 80% of hurricane-related deaths. A new scale could help people better prepare for storms.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A new hurricane categorization system could help people better prepare for storms by incorporating risks from storm surges and rainfall into the categories, a study published this month reveals.

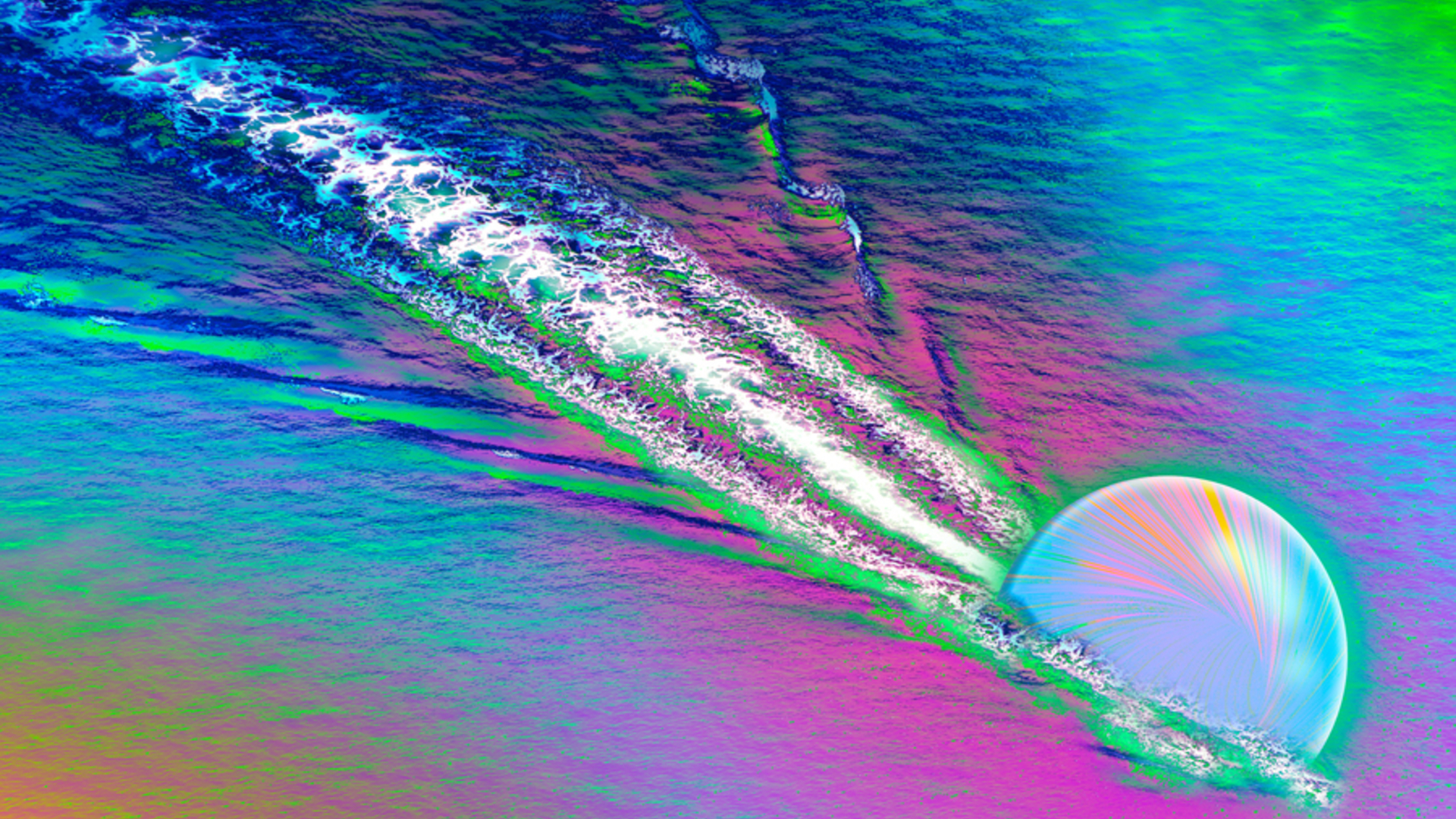

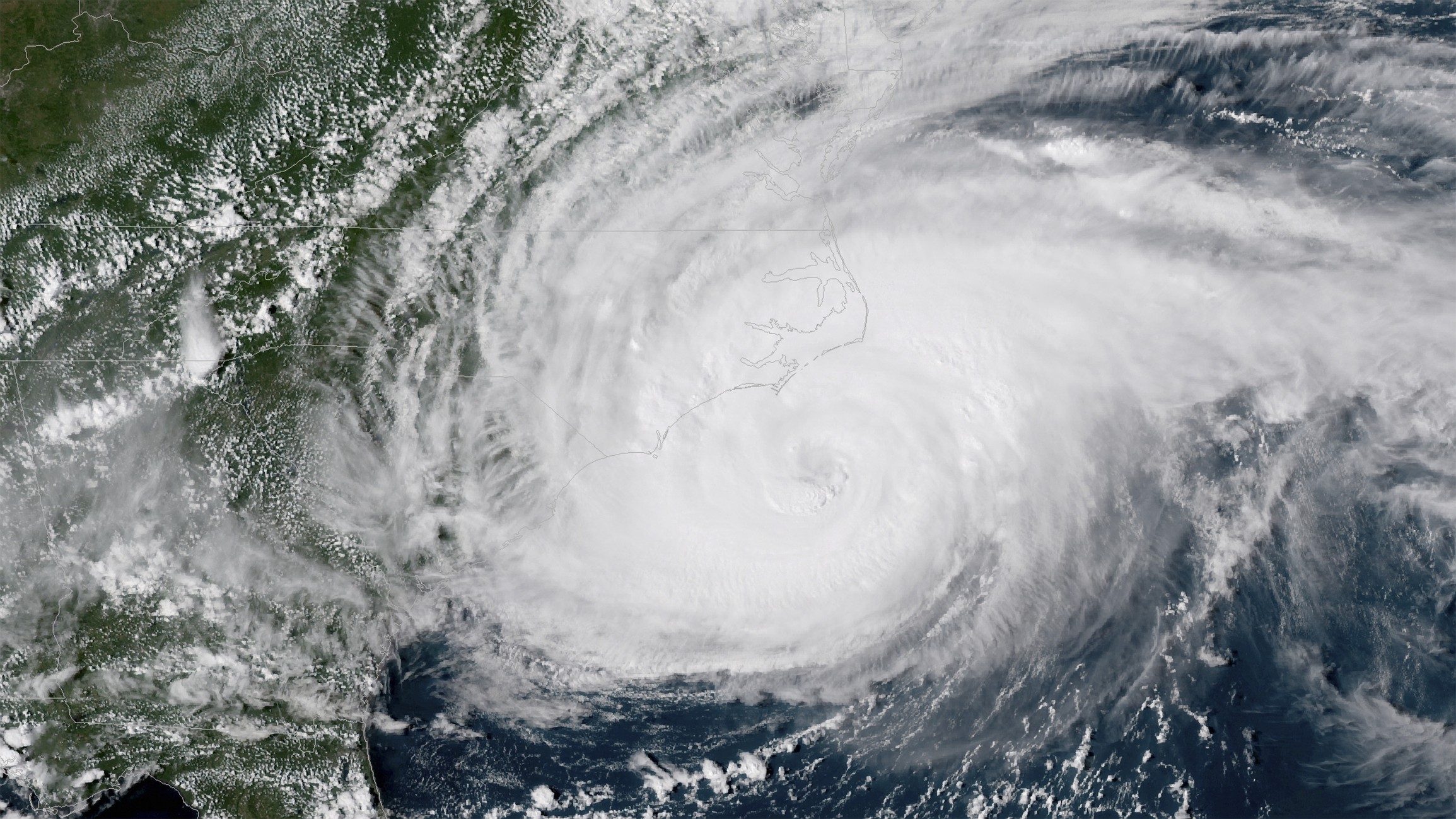

Storm surges — elevated seawater levels near coasts — and rainfall cause almost 80% of hurricane deaths, yet they are not accounted for in the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale (SSHWS), which forecasters currently use to categorize a hurricane's severity and plays a key role in communicating hurricane risk to the public. Some experts have previously argued that the threat of storms is not always properly reflected in the SSHWS's 1 to 5 category ratings, which are based solely on wind speed.

"There have been too many instances of incredible loss of life and destruction because a low category number on the SSHWS [...] did not match the danger of the storm," Jennifer Collins, a professor in the School of Geosciences at the University of South Florida and co-author of the new study, said in a statement.

The SSHWS estimates potential property damage from sustained wind, ranging from "some damage" in a Category 1 hurricane to "catastrophic damage" in a Category 4 or 5 storm. But property damage isn't the only potentially deadly effect of a hurricane. A low-category hurricane may still cause a tremendous tidal surge and unleash torrential rain, triggering devastating floods and other hazards.

One example is 2005's Hurricane Katrina, which was listed as a Category 3 based on wind speeds. But storm surge and rainfall were responsible for most of the 1,800 deaths caused by Katrina and contributed hugely to the $125 billion in damage, according to the new study.

Another example is Hurricane Florence, which made landfall in South Carolina in 2018 as a Category 1. The low danger rating did not alert communities to the catastrophic flooding that killed 55 people across the southeastern U.S., the researchers said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Frequently, people use the storm's category to decide whether to evacuate," Collins said. "That's incredibly dangerous because if they hear it's only a tropical storm or Category 1, too often no alarm bells go off, and they see no cause for concern."

To address the SSHWS's shortcomings, Collins and colleagues developed an alternative hurricane warning system in 2021. Dubbed the Tropical Cyclone Severity Scale (TCSS), this system has six categories and takes into account wind speed, storm surge and rainfall — the three biggest hazards from hurricanes.

The TCSS assigns scores between 1 and 5 to each of the three hazards depending on their predicted severity for a given hurricane. These scores are then combined into a final score, which is established using three rules in different scenarios.

First, the final score is never lower than the highest of the three individual hazard scores. Second, if two individual hazards have the same scores of 3 or higher, then the final score increases by one — so, if storm surge has a score of 2 but wind and rainfall are both 3, then the hurricane is classed as a Category 4. The third rule is that a final score of 6 is given if either two hazards have scores of 5, or if two hazards have scores of 4 and the third is a 5.

"The higher category is important," Collins said. "Many people base their decision to evacuate on that number, not just the details of the hazard."

A "more realistic" system

Researchers have been working on the TCSS for several years, but the new study looked to confirm its effectiveness at warning the public of a hurricane's dangers. To test their warning system, Collins and her colleagues sent 4,000 participants living along the Gulf and East coasts forecasts for 10 fictitious hurricanes affecting their communities.

Half of the participants received warnings in the SSHWS format, while the other half received warnings using the TCSS system. They then completed an online quiz about how they would react in the different scenarios. The team’s findings were published Aug. 19 in the journal Scientific Reports.

Participants who were sent TCSS forecasts were more likely to identify the main hazard from a hurricane correctly, and significantly more likely to evacuate for non-wind hazards than those who were sent SSHWS forecasts, according to the study.

Correct identification of the main hazard boosted participants' intent to take relevant precautions, such as shielding their houses against flooding with sandbags and erecting window protections against the wind. On the other hand, participants who had incomplete information about a storm were more likely to miscalculate risks or take no measures at all.

The results suggest that shifting away from the SSHWS would improve the public's understanding of hurricane risks and lead to more informed decision-making ahead of storms, Collins said.

"I'm fairly optimistic that now is the time," she said. "We now know many people make decisions based on the category messaging, so we need to ensure that we are communicating with a scale which is more realistic of the severity of the hurricane."

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus