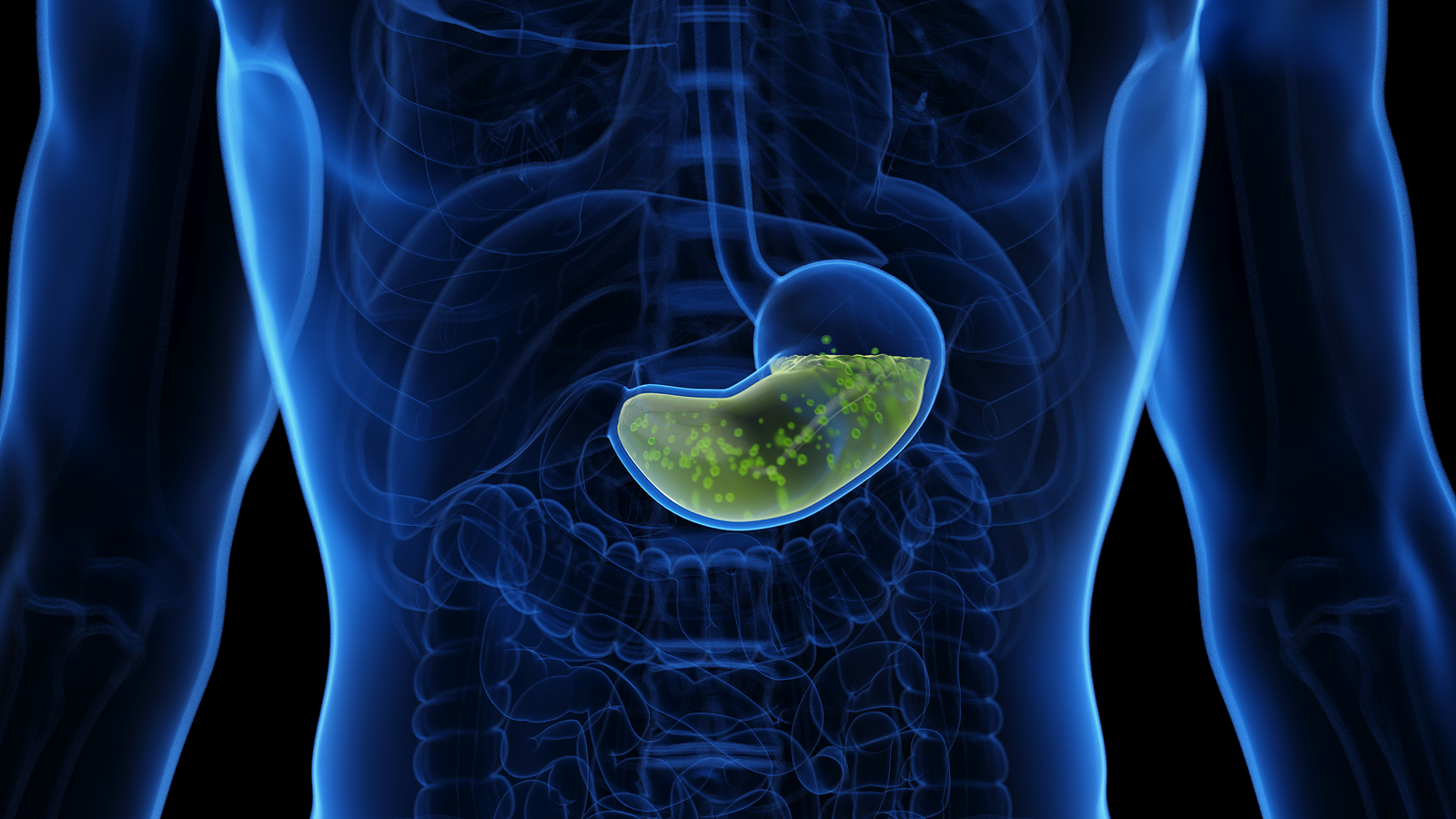

Why doesn't stomach acid burn through our stomachs?

The hydrochloric acid in your stomach can burn through metal — so why doesn't it burn through your stomach?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

If you're about to throw up or get acid reflux, you may feel a burning sensation when acid from your stomach escpes into the esophagus. But if stomach acid is harsh enough to irritate the inside of your throat, why doesn't it burn through your stomach?

The human stomach evolved to create and withstand extremely corrosive conditions. "Its role is to break down the components of physical food into smaller pieces, with the idea being that, by the time the preparation reaches the small bowel, it's in small enough components that we can absorb it," Dr. Sally Bell, a gastroenterologist at Monash University in Australia, told Live Science.

The stomach contains specialist cells with the sole job of producing destructive chemicals to aid digestion. The main component of this gastric juice is hydrochloric acid, a potent chemical that's strong enough to dissolve metal. There are also smaller amounts of the digestive enzymes pepsin and lipase, which break down proteins and fats, respectively.

This harsh environment also has a secondary defensive role, said Dr. Benjamin Levy III, a gastroenterologist at University of Chicago Medicine. "Gastric juices also help the body kill bacterial pathogens so that we don't get sick and strategically impede the development of bacterial overgrowth," Levy told Live Science. This is especially important for destroying potential foodborne pathogens, he said.

Sign up for our weekly Life's Little Mysteries newsletter to get the latest mysteries before they appear online.

Without protection, this combination of strong acid and protein-digesting enzymes would quickly begin to eat into the stomach wall, first forming painful ulcers before ultimately burning a hole. However, cells that line the inside of the stomach — a layer known as the epithelium — have developed a special secretion to protect the organ from attack.

"These cells are unique in that they produce this very thick, sticky layer of mucus which is alkaline and buffers the acid," Bell explained. "It's proteinaceous material that is rich in bicarbonate, essentially, so it protects the stomach lining from its own acid and its own enzymes."

In a healthy digestive system, this mucous barrier covers the walls of the stomach and is continually renewed by the epithelial cells to provide constant protection. However, problems can arise when the layer becomes damaged. Even small breaks can allow acid and pepsin to penetrate under the mucus, which can lead to chronic inflammation and ulcers, Levy said.

One cause of such damage is the overuse of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen and naproxen. "NSAIDs damage the stomach lining by inhibiting cyclooxygenase (COX-1)," an enzyme that's responsible for the production of hormone-like compounds called prostaglandins, Levy said.

"This reduces prostaglandin production, which causes a decrease in both mucus and bicarbonate secretion," Levy explained.

Certain lifestyle choices, such as smoking or drinking, can also increase the risk of this type of digestive disorder by acting as direct toxins to the lining, Bell noted. In addition, acidic or spicy foods can overwhelm the stomach's natural protection to cause irritation or trigger reflux into the esophagus.

Despite the extremely acidic conditions, it's possible for bacterial infections to sometimes cause problems in the stomach. For example, "Helicobacter pylori have the ability to secrete proteases and lipases that degrade the gastric mucus and harm the phospholipid layer of the epithelial surface," Levy said. Once detected, H. pylori can be treated with a combination of antibiotics.

The bottom line? Stomach acid plays an integral role in digestion and defense against disease, so the organ has developed a remarkable capacity to protect itself and renew its lining.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Victoria Atkinson is a freelance science journalist, specializing in chemistry and its interface with the natural and human-made worlds. Currently based in York (UK), she formerly worked as a science content developer at the University of Oxford, and later as a member of the Chemistry World editorial team. Since becoming a freelancer, Victoria has expanded her focus to explore topics from across the sciences and has also worked with Chemistry Review, Neon Squid Publishing and the Open University, amongst others. She has a DPhil in organic chemistry from the University of Oxford.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus