Something supercharged Uranus with radiation during Voyager flyby 40 years ago. Scientists now know what.

Forty years ago, Voyager 2 flew past Uranus and observed radiation levels that defied explanation. Now, scientists may finally know exactly what happened.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Scientists may have solved a long-standing mystery surrounding Uranus' extraordinarily strong radiation belt.

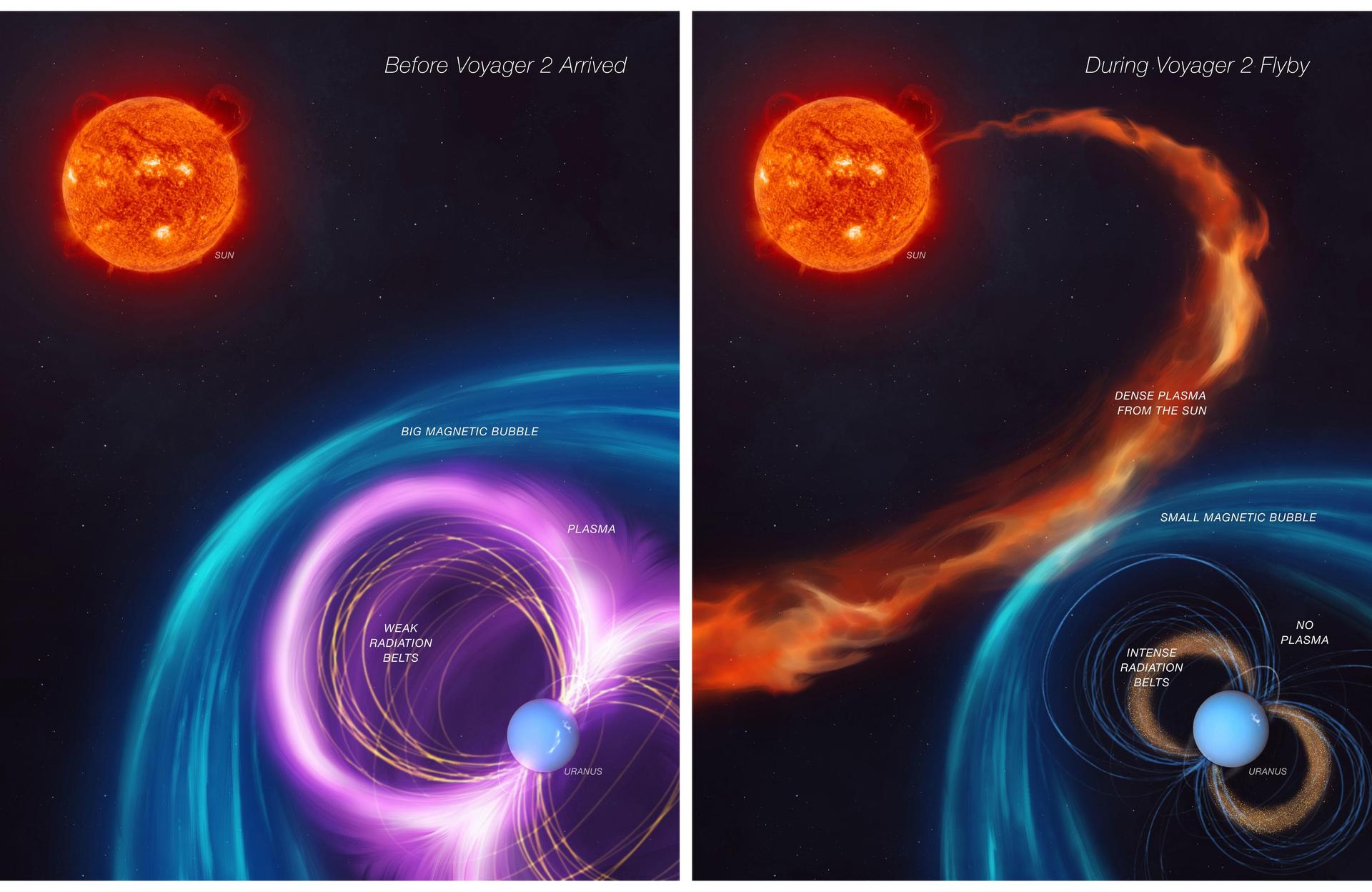

A new analysis of Voyager 2 data suggests that a temporary space weather event may have made the planet's electron radiation belt more intense than usual as Voyager 2 was passing by. The findings could help to explain why the radiation belt was so much stronger than scientists had predicted it would be.

Radiation belts are formed from interactions between the solar wind and a planet's magnetic field. The sun emits a continuous stream of protons and electrons from its outer atmosphere, called the corona. For planets that have a global magnetic field, including Earth and Uranus, some of those energetic, charged particles get trapped in the magnetosphere.

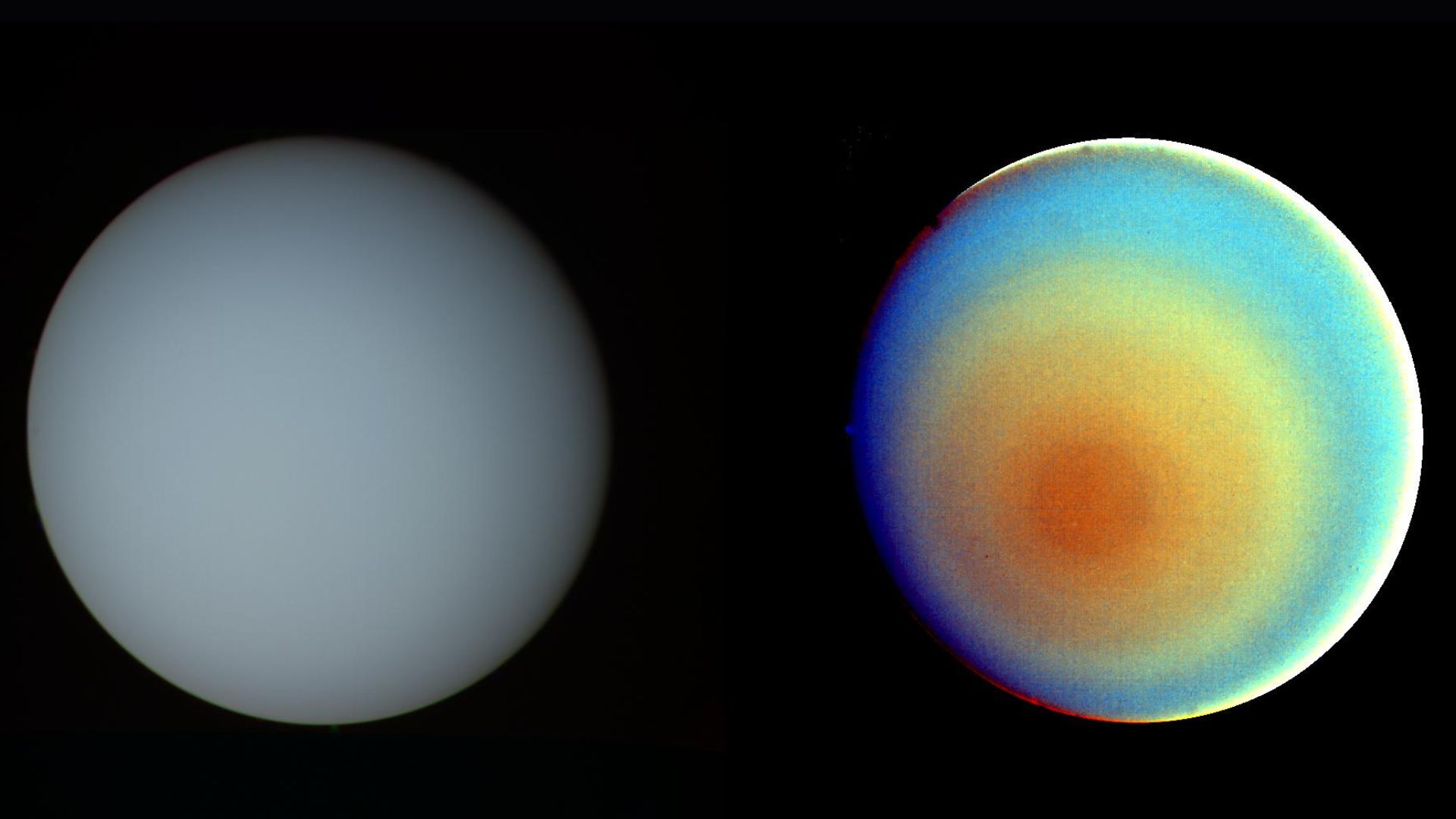

Article continues belowIn January 1986, Voyager 2 flew by Uranus and measured the strength of its radiation belts. While the ion radiation belt was a little weaker than expected, the electron radiation belt was much more intense than scientists had predicted — close to the maximum intensity Uranus could sustain. Since then, scientists have tried to figure out how and why this was the case.

"Science has come a long way since the Voyager 2 flyby," Robert Allen, a space physicist at the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) and coauthor of the new research, said in a statement. "We decided to take a comparative approach looking at the Voyager 2 data and compare it to Earth observations we've made in the decades since."

Earth versus Uranus

In the study, published in November 2025 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, Allen and colleagues revisited data collected by Voyager 2 during its flyby of Uranus. They found several similarities between the Voyager data and the data collected from Earth orbit during a space weather event in 2019.

Uranus' unusually intense radiation belt may have been caused by a "co-rotating interaction region," the team found. A co-rotating interaction region occurs when high-speed solar winds overtake slower solar wind streams. The phenomenon could have accelerated electrons and added energy to the radiation belt, the researchers said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"In 2019, Earth experienced one of these events, which caused an immense amount of radiation belt electron acceleration," said study co-author Sarah Vines, a space physicist at SwRI. "If a similar mechanism interacted with the Uranian system, it would explain why Voyager 2 saw all this unexpected additional energy."

If that's the case, it raises many more questions about the physics of Uranus' magnetosphere and its interactions with the solar wind, including the radiation belt's stability during the extreme seasons caused by the planet's tilted axis of rotation. A spacecraft orbiting Uranus and collecting data from different parts of the magnetosphere could help address those questions, the researchers wrote in the study.

"This is just one more reason to send a mission targeting Uranus," Allen said in the statement. "The findings have some important implications for similar systems, such as Neptune's."

Allen, R. C., Vines, S. K., & Ho, G. C. (2025). Solving the mystery of the electron radiation belt at Uranus: leveraging knowledge of Earth’s radiation belts in a Re‐Examination of Voyager 2 observations. Geophysical Research Letters, 52(22). https://doi.org/10.1029/2025gl119311

Skyler Ware is a freelance science journalist covering chemistry, biology, paleontology and Earth science. She was a 2023 AAAS Mass Media Science and Engineering Fellow at Science News. Her work has also appeared in Science News Explores, ZME Science and Chembites, among others. Skyler has a Ph.D. in chemistry from Caltech.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus