Sexy Swimmers: 7 Facts About Sperm

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Surprising sperm

With every ejaculation, men produce around 200 million sperm cells. How much do you know about these wiggly little cells? Read on for 7 surprising facts about sperm.

They respond to your diet

Want supercharged sperm, or just a nudge to the slow guys? Turns out, studies suggest some nutrients are good for sperm quality and quantity. For instance, studies in mice have suggested the fatty acid found in fish called docosahexnoic acid, or DHA, is essential for sperm formation. Researchers reported why DHA is so critical in October 2011 in the journal Biology of Reproduction; they found that DHA turns dysfunctional round-headed sperm into strong swimmers with cone-shaped heads packed with egg-opening proteins.

For older men, an antioxidant-rich diet, or multivitamin, may be in order. A study by scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory found that men over 44 with high vitamin-C diets had 20 percent less DNA damage to sperm than their peers who consumed the least vitamin C. Antioxidants, vitamin E, zinc and folate had similar effects, the researchers reported in 2012 in the journal Fertility and Sterility.

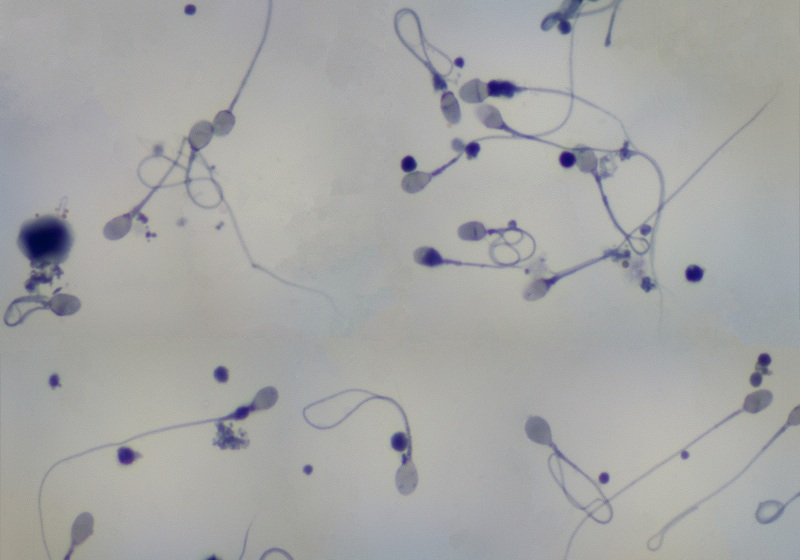

They're funny-looking

The well-ingrained persona of a healthy sperm is one with a smooth oval head and a long somewhat ungulating tail. Turns out guys, most of your sperm are not so photogenic. "[W]ith fairly generous criteria, (like normal means one oval head with one tail,) only about a third of a man's sperm look normal. That means, for most men, most of their sperm are funny looking," writes Dr. Craig Niederberger on his male fertility blog called Male Health.

Defects to sperm can occur in any of the sex cell's three parts: the head, midpiece (the neck) or the tail, or a combination of these. For instance, a defective sperm could have double heads, small or oversized head, a bent neck, thin midpiece, a tail that's bent, broken or coiled, or multiple tails. Whether these morphological anomalies make for less potent sperm is still up for debate, according to Niederberger, chief of the department of urology at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

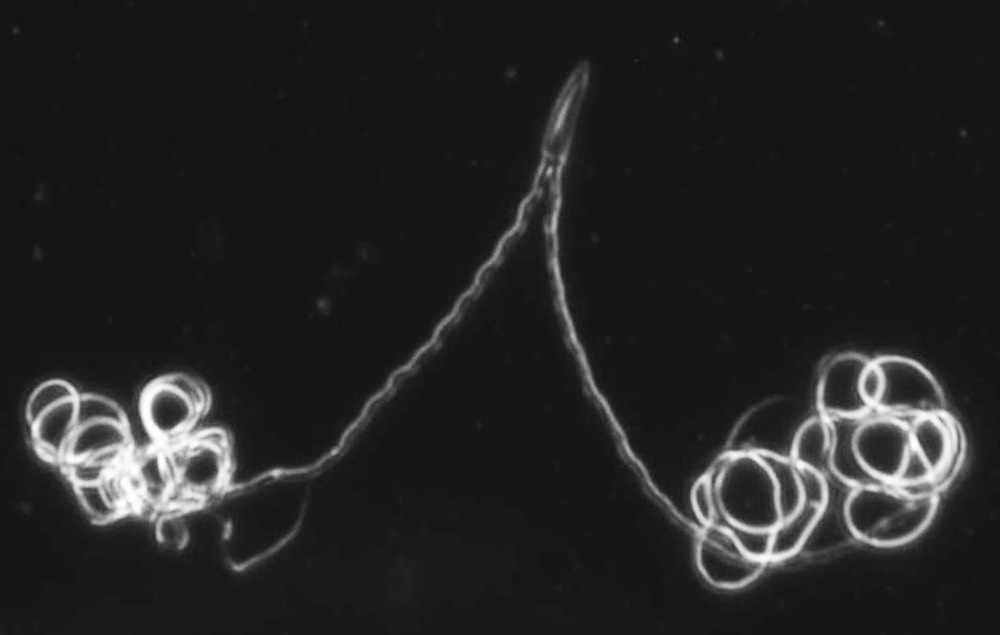

Animals have you beat

Humans may have odd-looking sperm, but the prize for weird sex cells goes to the animal kingdom (the non-human one). Take the male diving beetle whose sperm, rather than going it alone, travel in pairs, clusters and even in chains of hundreds or thousands of the swimmers. The odd teamwork may be the result of beetle sperm having to keep up with the ever-evolving reproductive tracts of female diving beetles. "When you look at the intricate morphology of the reproductive tracts, you can't help but think that sperm needs Swiss army knives and compasses to make it through there," study researcher Scott Pitnick, a biologist at Syracuse University in New York, said in a statement. "The females make it really complicated."

Take the sperm of the male diving beetle, which is seriously strange: Instead of swimming in the female reproductive tract on their own, individual sperm cells often stick together in pairs, in clusters and even in long chains of hundreds or thousands. And then there are the naked mole rats whose bizarre looks are paired with equally odd sperm: Researchers found most of their sperm can't even swim, with 0.just 0.1 percent considered fast swimmers. Even so the males with mutant sperm fathered offspring.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

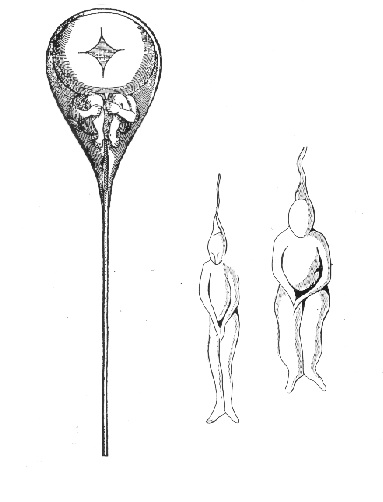

Discovered by a Dutchman

Sperm were not discovered until 1677, when Dutch microscope-maker Antony van Leeuwenhoek reported seeing “animalcules” moving like eels in a sample of his own semen under the microscope lens. (van Leeuwenhoek was quick to assure his readers that the sample came from an “excess” left over from conjugal relations rather than by masturbation.)

“Their bodies were rounded, but blunt in front and running to a point behind, and furnished with a long, thin tail,” van Leeuwenhoek wrote in his initial report.

Long misunderstood

Antony van Leeuwenhoek may have discovered a new world of cells in seminal fluid, but he was very mistaken about how sperm work to fertilize eggs. In fact, the process of fertilization wasn’t proven until 1879, according to “A Mind of its Own: A Cultural History of the Penis” (The Free Press, 2001). In the 1600s, researchers believed that humans came preformed, curled in miniature inside either the egg or the sperm. “Spermists,” as the believers in the latter theory were called, even claimed to be able to see tiny humanoids inside the head of sperm cells. These spermist argued that women simply provided an incubator for the male seed.

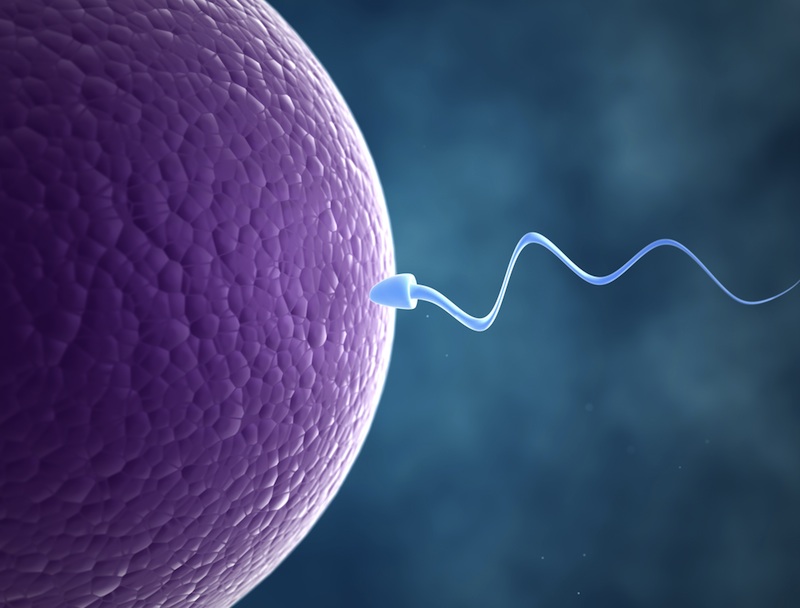

They get a little help

Sperm are strong little swimmers, but they get help when it comes to penetrating the egg. A burst of the female-produced hormone progesterone encourages sperm to wiggle their little tails frantically in order to push through the egg’s protective membrane. A protein called catsper in sperm cells is responsible for recieving the hormonal signal, researchers reported in 2011 in the journal Nature.

Macho men may not have super-sperm

Women tend to be attracted to men with deep, manly voices. But research published in Dec. 2012 in the journal PLos ONE finds that these macho guys have no better sperm quality than gentlemen with high-pitched voices. In fact, sperm concentration in deeper-voiced men was lower than in men with higher voices.

It’s possible that a deep voice sends shivers down a woman’s spine because deep voices are linked with testosterone levels, the researchers wrote. However, a high enough level of testosterone can actually impede sperm production, suggesting that the drop in sperm concentration might be an evolutionary trade-off.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus