The US Lost 1 Warship in WWI. 100 Years Later, We Know What Caused the Sinking.

The only major U.S. warship lost in World War I was brought down by a German mine, new research confirms.

The USS San Diego sank about 8 miles (13 kilometers) from Fire Island, New York, on July 19, 1918. Although the ship went down rapidly — in just 28 minutes — 1,177 crewmembers survived and only six died. Naval historians had long suspected that a German submarine, U-156, was responsible for the sinking, but no one knew whether the weapon was a mine or a torpedo or if there was some other explanation, like sabotage or an accidental explosion.

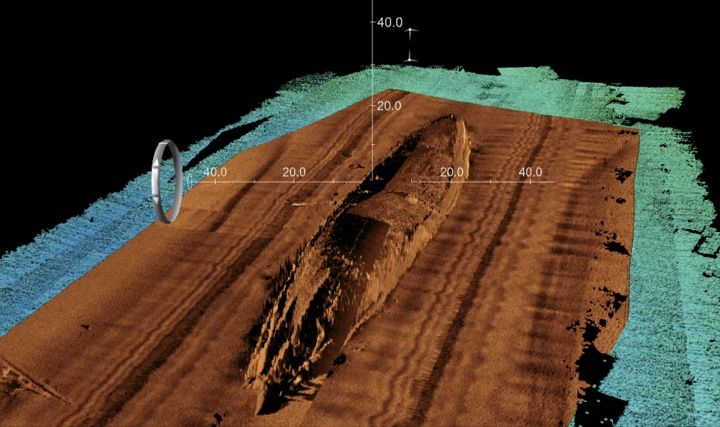

Now, a new high-resolution sonar scan and dive exploration of the wreck have revealed that the sinking was almost certainly the work of the German sub. [The 20 Most Mysterious Shipwrecks Ever]

"We believe U-156 sunk San Diego, and we believe it used a mine to do so," said Alexis Catsambis, a maritime archaeologist with the Naval History and Heritage Command.

A century-old mystery

Catsambis and his team announced their findings Dec. 11 at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU) in Washington, D.C. Their exploration of the wreck, the first comprehensive study since the 1990s, revealed that the ship still sits, largely intact but upside down, in about 115 feet (35 meters) of water.

The research team explored the wreck in advance of 2018's 100-year anniversary of the vessel's sinking. That exploration included one dive during which divers laid a commemorative wreath at the site. The researchers used high-resolution sonar techniques to image the wreck in three dimensions, getting a detailed view of the hull where the explosion occurred at 11:23 a.m. on July 19, 1918. At the time, the ship was working to escort convoys of military and supply ships on the first leg of the journey to Europe.

The imaging revealed that the thick armor band encircling the ship has held the wreck together "like a girdle," Catsambis told reporters. The wreck has become a vibrant artificial reef, providing a home for marine life, from barnacles to anemones to fish and lobster, said Catsambis' colleague Arthur Trembanis, a University of Delaware geological oceanographer. [Mayday! 17 Mysterious Shipwrecks You Can See on Google Earth]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But the elements are working on the USS San Diego. Sometime since the 1990s, the middle part of the ship's hull collapsed in on itself, the researchers found. In the shallow waters where the wreck rests, large storms can scour the seafloor and anything on it, Trembanis said. An average of about three storms per year in the area are large enough to rearrange the USS San Diego wreck, he said.

Mystery mine

Fortunately, the ship was still intact enough for researchers to gather information necessary to explain what happened on that summer day in 1918. The size and location of the damage, when combined with archival crew descriptions of the subsequent flooding, quickly ruled out a coal-dust explosion or crew sabotage, said Ken Nahshon, an engineer at the Carderock Division of the Naval Surface Warfare Center in Maryland, who created computer models simulating the sinking.

That left, for explanations, a mine or torpedo, either of which could have been launched by a German submarine. The damage to the hull wasn't extensive enough to match a torpedo attack, Nahshon told reporters. And 17 lookouts on the USS San Diego failed to notice any distinctive bubble trail that torpedoes of the time made as they sliced through the water. It was a clear day with calm seas, and the crew knew German subs were operating in the area, Catsambis said, so it's unlikely the lookouts would have missed such a telltale sign.

Far more likely, Nahshon said, was that the USS San Diego hit a mine, either a T1/T2 torpedo tube mine, which would have been shot from the German submarine's torpedo tube, or a deck-deployed mine, which would have been laid from the sub's deck.

The simulations re-created how the mine would have brought the ship down. Within 2 minutes, Nahshon said, the region of impact was flooded. Within 10 minutes of the explosion, the ship was listing to the side enough that water poured into the gun deck.

"This water rushing from above really causes a catastrophic situation," Nahshon said.

Under the weight of that water, the ship kept listing toward the port side. According to the Navy, the captain ordered full steam toward the beach, hoping the ship would sink in shallow, salvage-deck waters. In the meantime, the crew manned the guns, shooting at anything that looked like a sub. They kept firing until the guns on the port side dipped underwater and the guns on the starboard side were shooting toward the sky.

At 11:20 a.m., Capt. Harley Christy ordered the crew to abandon ship.

"He has literally minutes to go before this thing just goes completely over," Nahshon said.

Eight minutes after the order went out, the ship flipped and slipped beneath the waves.

Past and future

Naval researchers pinpointed U-156 as the source of the likely mine, because documentation after the war revealed that the sub was in the area at the time. Just a few days later, on July 22, that sub would execute the only World War I attack on the U.S. mainland, by firing at some tugboats off the coast of Massachusetts.

The submarine never made it back to Germany. It hit a U.S.-laid minefield in the North Atlantic and sank before the war ended. The wreck has yet to be found.

The findings of the USS San Diego exploration will be used to help protect and preserve the wreck, Catsambis said, and to inform the management of other World War I and World War II wreck sites. These discoveries also confirm that the crew of the San Diego was not to blame for what befell them. The ship's captain took all possible precautions and did everything right in responding to the attack, Catsambis said.

"They were prepared," he said, "and tragedy struck."

- In Photos: Searching for Shackleton's 'Endurance' Shipwreck

- Shipwrecks Gallery: Secrets of the Deep

- In Photos: WWII-Era Shipwrecks Illegally Plundered in Java Sea

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.