The Bering Land Bridge has been submerged since the last ice age. Will scientists ever study it?

Humans likely left a lot of archaeological evidence along the Bering Land Bridge when they crossed from Asia to Alaska during the last ice age. But will we ever be able to dive down to examine it?

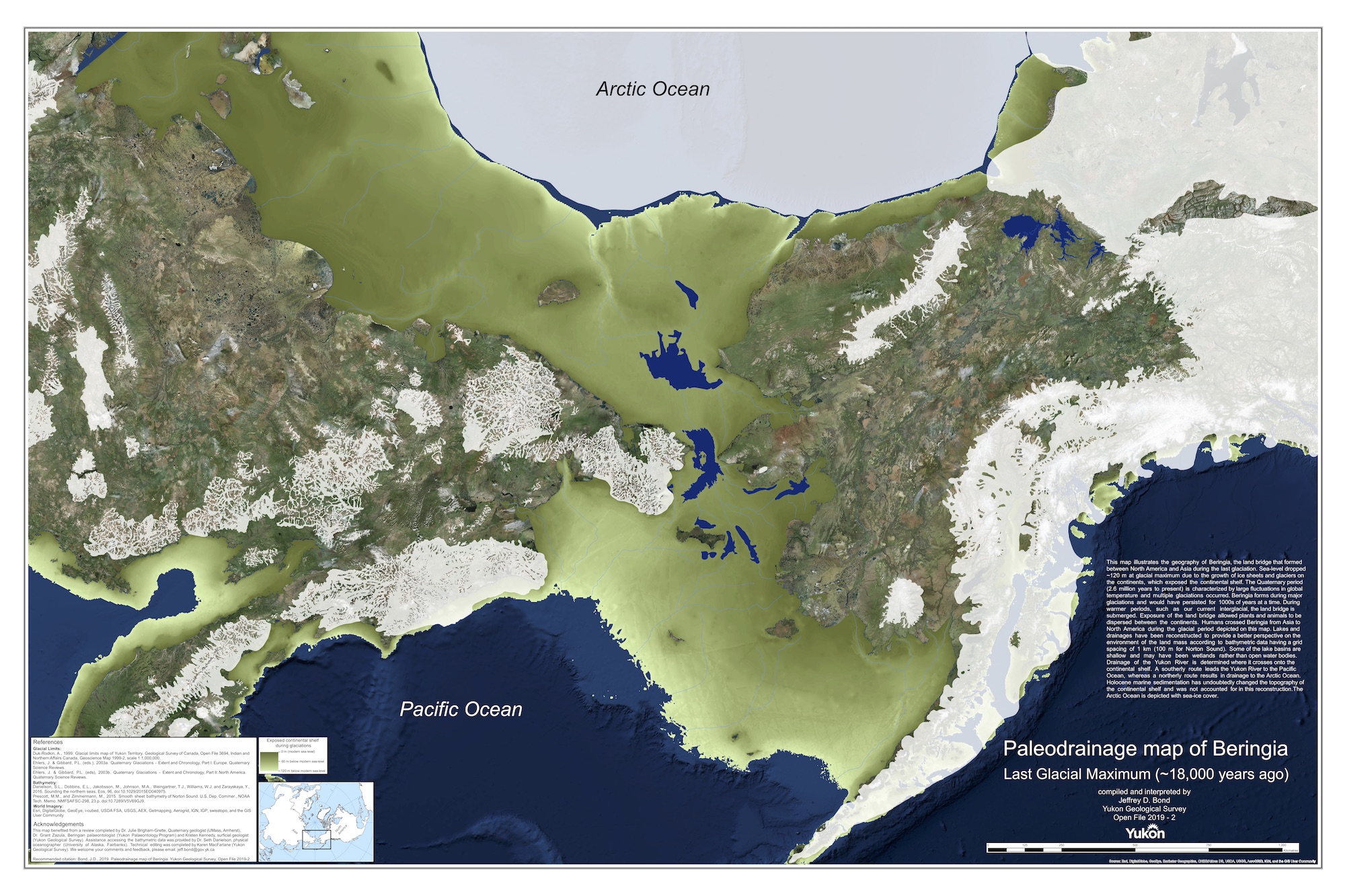

The Bering Strait is a 52-mile-wide (85 kilometers), 165-foot-deep (50 meters) stretch of water between Alaska and Siberia. Today, it divides North America and Asia. However, during the coldest part of the last ice age between about 26,500 and 19,000 years ago, as the planet's water became frozen in massive ice sheets, global sea levels were about 425 feet (130 m) lower. The resulting Bering Land Bridge let animals such as mammoths and horses roam between Asia and the Americas.

Much remains debated about whether and how humans used the Bering Land Bridge to migrate to the New World. For instance, a 2022 study found that this strip of land may have been blocked by an icy barrier by the time humans could have come to it. As such, the first people in the Americas may have boated or walked along the bridge's coast instead of trekking across its interior on foot.

Given the potential to shed light on early human migrations, will archaeologists ever study the drowned land that was once the Bering Land Bridge? And what might they find there?

Exploring the buried Bering Land Bridge would be exceedingly difficult and costly, but the archaeological payoff could be extraordinary, experts told Live Science.

What ice age artifacts would we find?

Ideally, scientists would dig into the Bering seafloor to find signs of ancient human migrants.

Sign up for our weekly Life's Little Mysteries newsletter to get the latest mysteries before they appear online.

"We have only a handful of archaeological sites in this area from the end of the ice age, so literally any site we find could completely change what we know about these early people," Jessi Halligan, an underwater archaeologist at Texas A&M University, told Live Science.

The chances are high that human sites and human remains could survive after millennia underwater. Because of the cold water of the Bering Strait, "any animals, clothing fragments, housing bits, charcoal, or other organic remains the people left behind are much more likely to have preserved because the cold water has fewer microbes to destroy them than can be found in open air or warmer water," Halligan said. "These sites could potentially be almost pristine."

However, actually making such discoveries in the Bering Strait "is a monumental challenge," Morgan Smith, director of the geoarchaeology and submerged landscapes lab at the University of Tennessee, Chattanooga, told Live Science. "The conditions there can become super-unmanageable super-fast."

The challenges of a Bering Strait excavation

To start with, the Bering Strait's frigid climate makes research there challenging. Ice is an obstacle for a significant chunk of the year, and the cold water there can prove a miserable experience for divers wishing to swim in it, Halligan said. Smith added that the area can experience fast currents, potentially making underwater work difficult.

In addition, "to give you an idea of the problems the weather poses, the Discovery Channel show 'The Deadliest Catch' takes place in the Bering Sea," Jesse Farmer, a paleoceanographer at the University of Massachusetts Boston, told Live Science. "The shallow seas there can get really rough very quickly when there's a storm. It's an extremely variable place in terms of weather — you need to get lucky with the conditions you face."

Moreover, there is the challenge all underwater archaeology faces: the water, Halligan noted.

"It is absolutely possible to send divers down to swim around and look for artifacts," Halligan said. However, this only works "when the seafloor is not covered by a bunch of marine sand that would have buried any traces of former landscapes and sites." This makes discovering potentially interesting sites through visual inspection essentially impossible.

Furthermore, "divers can only safely dive to about a max of 130 feet [40 m] deep," Halligan said. "At that depth, they can only be down a few minutes, so it is not a practical solution to cover very much of the seafloor."

Farmer noted that at least 10 to 50 feet (3 to 15 m) of sediment would have settled on the seafloor in the past 10,000 to 11,000 years. "You can't just look around with a submersible if you don't know where to look," Farmer said. Smith noted that "it's a real needle-in-a-haystack problem."

When it comes to archaeology on land, researchers often dig small pits about 12 to 20 inches (30 to 50 cm) wide in promising areas to look for archaeological evidence.

"There is no equivalent to shovel test pits underwater," Halligan said. "Our closest attempt is taking cores, which are tubes or pipes forced vertically through the layers of the seafloor. These are usually 10 centimeters [4 inches] in diameter, and usually no more than a few dozen can be obtained from an area due to the time and cost investment."

Given such a large stretch of land to cover, attempting to find ancient sites with a few cores at a time might prove extraordinarily difficult.

"You can always get lucky — many amazing scientific discoveries have been made by sheer luck," Farmer said. "But luck doesn't get you funding."

The remote location of the Bering Strait also makes expeditions there expensive. "You need huge research vessels to go there, and those can cost $8,000 to $15,000 a day, not including fuel," Smith said. "These are really busy boats, so you have to reserve them a year in advance; you can't predict weather even 10 days in advance, so you have to hope that you don't have bad luck during your trip."

Currently, to find drowned sites, researchers first look for signs that details of the former landscape might actually have been preserved. This involves sonar, which uses sound waves to reveal objects or topography below, to peer at these former landscapes under sediment.

"It gives us a place to send divers down and/or take cores to look for artifacts or the traces of human activity — like, for instance, bacteria associated with humans and not other animals," Halligan said. "Cores that have already been extracted from the area have contained insect and pollen remains that have really helped us refine our understanding of past environments in the area."

Scientists have made some forays into exploring the Bering seafloor, "mostly done by researchers who have gotten funding from NOAA and Parks Canada," Halligan said. "Oil companies probably have done remote sensing surveys of much of the area. But they are not required to make their data public, so it is not available to archaeologists for the most part."

All in all, Bering seafloor research would "take time and money, but the outcomes could be extremely exciting," Halligan said. "There are almost certainly sites out there."

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.