Ice Age 'Unicorn' May Have Lived Alongside Modern Humans

A burly "unicorn" that once plodded over grasslands in Siberia was around for much longer than once thought — long enough to have roamed the land at the same time as modern humans.

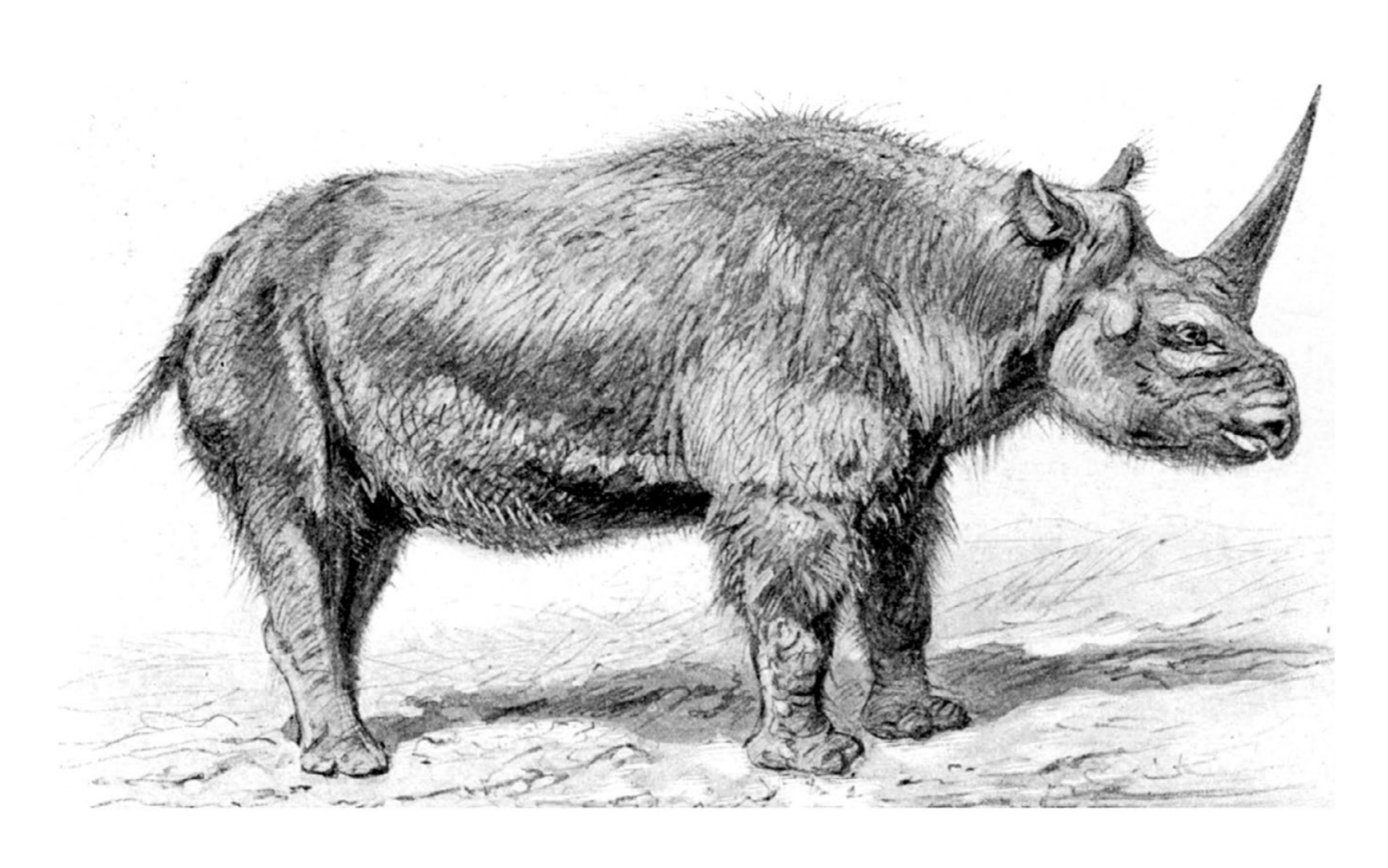

This one-horned native of the steppes, Elasmotherium sibiricum, was a hefty, furry beast in the rhino family that weighed nearly 4 tons — more than twice the weight of a white rhinoceros, the largest species of modern rhino.

Previous interpretations of E. sibiricum bones suggested that they died out 200,000 years ago, but recent analysis hints that E. sibricum fossils are much younger than that, dating to at least 39,000 years ago and possibly as recently as 35,000 years ago, according to a new study. This would mean that the "unicorn" was still around when people populated the region, the scientists reported. [10 Extinct Giants That Once Roamed North America]

All of the known E. sibiricum bones are part of fossil collections representing either deposits that had a range of ages, or deposits that were around 200,000 years old. Siberian "unicorns" were therefore thought to have gone extinct 200,000 years ago — long before a sweeping extinction of large Ice Age mammals that took place around 40,000 years ago, study co-author Adrian Lister, a researcher with the Earth Sciences Department at the Natural History Museum in the U.K., told Live Science in an email.

But the new findings suggested that E. sibiricum may have remained on the scene a lot later than that.

Dating a 'unicorn'

The researchers looked at 25 bone samples and found 23 that still held enough collagen to be analyzed using radiocarbon dating — a method that determines a specimen's age based on the amount of carbon-14 it holds. Carbon-14 is a radioactive isotope that forms naturally in green plants and in plant-eating animals. After one of those organisms dies, the carbon-14 it contained decays at a steady rate. By examining this isotope in bones, for example, and seeing how much carbon-14 is left, scientists can estimate how long ago the organism was alive.

Based on the radiocarbon data, the study authors concluded that the ancient rhinos were still around 39,000 years ago, placing them in Europe and Asia at the same time as humans and Neanderthals. This new time frame also means that E. sibiricum experienced the dramatic climate shifts that took place during that period. Since these grazing animals were adapted to a highly specialized lifestyle, effects brought about by a changing climate could have eventually nudged them into extinction, according to the study. [Image Gallery: 25 Amazing Ancient Beasts]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But while these findings significantly clarify when E. sibiricum was alive, it's still unclear when the rhino lineage finally went extinct, Ross MacPhee, a curator with the Department of Mammalogy at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, told Live Science.

MacPhee, who was not involved in the study, said that the scarcity of Elasmotherium fossils makes it difficult to say for sure when the species appeared and when it vanished.

"Rhino fossils are comparatively rare — they're not at all like wooly mammoths or bison in Siberia — and the fewer specimens you have, the less certain you can be. You don't really know where you are, with respect to the 'life cycle' of the species," MacPhee said.

In other words, Elasmotherium populations may have survived to even more recently than 39,000 years ago, but their remains were either entirely destroyed or have yet to be discovered.

Nevertheless, the study presents "good evidence" that the rhino was extinct by the last glacial maximum — when ice sheet coverage was at its peak — about 20,000 to 25,000 years ago, he added.

In 2016, another research group analyzed a partial skull of E. sibiricum, concluding that the bones were 29,000 years old, Live Science previously reported. But the amount of collagen the researchers extracted from the bone was so small that their results may have been contaminated by other materials in the fossils, and therefore may not represent the fossils' true age, MacPhee said.

Teeth like a rodent

More data from isotope ratios in E. sibiricum's tooth enamel told Lister and his colleagues that the animal probably grazed on dry, tough grasses. This allowed them to confirm prior interpretations of E. sibiricum's habitat and diet based on the shape of the teeth, which "are utterly unlike that of any other rhino," Lister explained.

"They are more like those of some giant rodent really. Being continuous growing and multi-folded, [the teeth] fit the extreme, tough grazing adaptation that we deduced from the stable isotope data," he said.

There are still many lingering questions about the so-called Siberian unicorn, but one that looms especially large is what its oversized horn may have looked like, Lister said. Giant horns are usually prominently featured by artists in reconstructions, but scientists have yet to uncover any evidence of a horn in the fossil record.

"We have no horn preserved, or even part of one, because they were made of compressed hair and have decayed," Lister explained.

"But the animal does have this huge bony boss at the top of its skull — much bigger than in any other rhino — so the horn must have been massive. Maybe one day we'll find one," he said.

The findings were published online Nov. 26 in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution.

- 6 Extinct Animals That Could Be Brought Back to Life

- Pleistocene Epoch: Facts About the Last Ice Age

- Photos: Perfectly Preserved Baby Horse Unearthed in Siberian Permafrost

Editor’s note: The story was updated on Dec. 3 to correct information about the timing of Elasmotherium's extinction.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus