Jupiter Now Has a Whopping 79 Moons

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

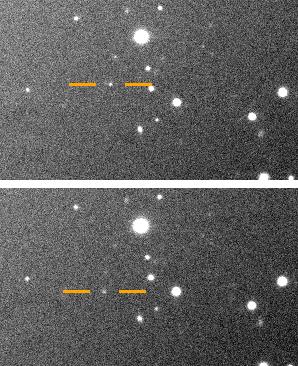

While hunting for the proposed Planet Nine, a massive planet that some believe could lie beyond Pluto, a team of scientists, led by Scott Sheppard from the Carnegie Institution for Science, found the 12 moons orbiting Jupiter. With this discovery, Jupiter now has a staggering 79 known orbiting moons — more than any other planet in the solar system.

Of the 12 newly discovered moons, 11 are "normal," according to a statement from the Carnegie Institution for Science. The 12th moon, however, is described as "a real oddball," because of its unique orbit and because it is also probably Jupiter's smallest known moon, at less than 1 kilometer (0.6 miles) in diameter, Sheppard said in the statement. [Photos: The Galilean Moons of Jupiter]

In the spring of 2017, these researchers were searching for Planet Nine in the region past Pluto, and "Jupiter just happened to be in the sky near the search fields where we were looking," Sheppard said. This gave the team a unique opportunity to search for new moons around Jupiter in addition to objects located past Pluto, according to the statement.

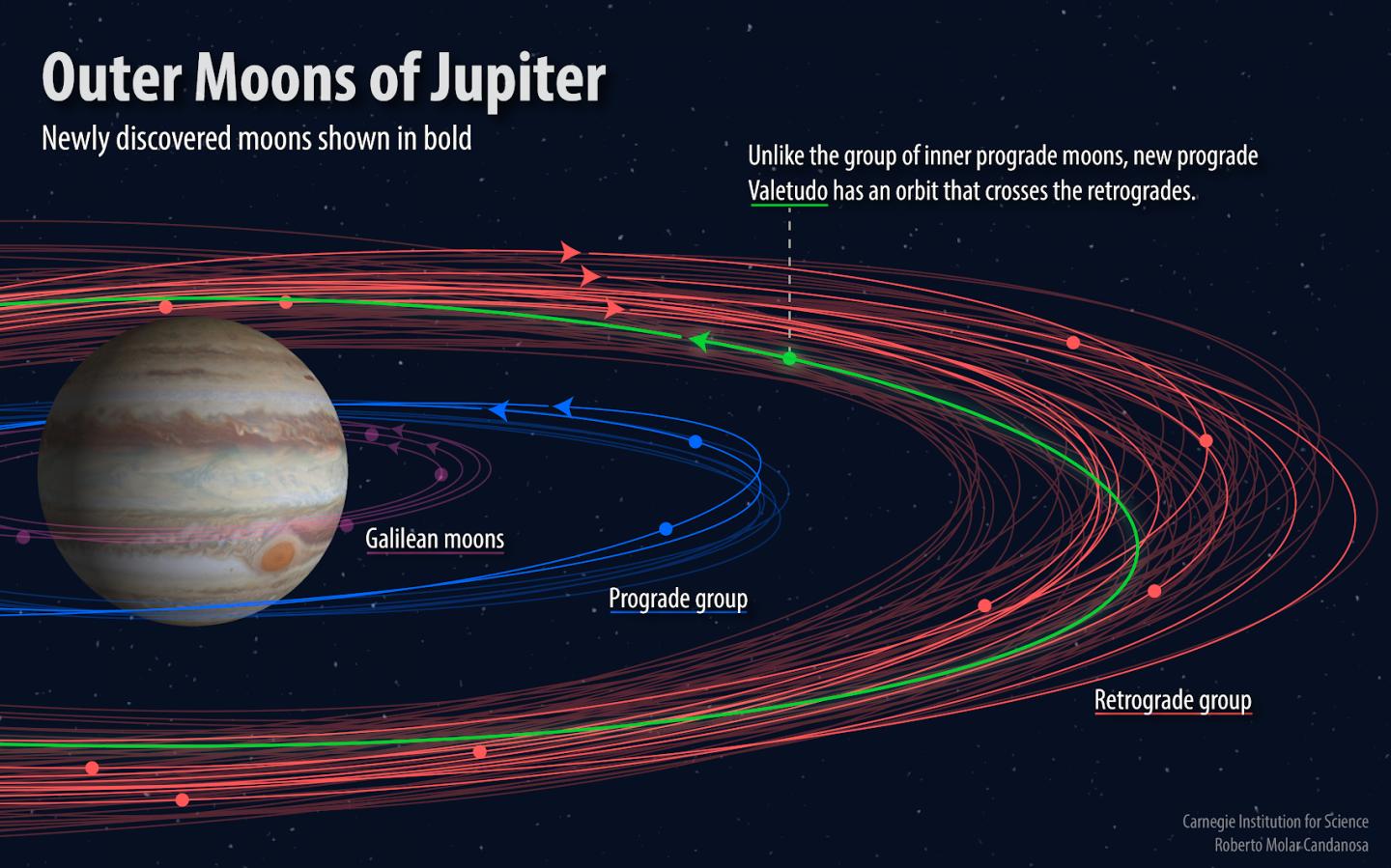

These two groups of prograde and retrograde moons consist of "irregular" satellites, or moons whose orbits have irregular, or noncircular, shapes.

In addition to these two groups, Jupiter has "regular" satellites, or moons with nearly circular orbits. These regular satellites consist of an inner group of four moons that orbit very closely to the planet and a main group of four Galilean moons that are Jupiter's largest moons.

The newly discovered "oddball" moon has a prograde orbit, but it orbits farther from Jupiter than the other moons in the larger prograde group and it takes about one and a half Earth years to complete an orbit. The satellite's oddness comes from its tiny size and the fact that, although it's out in the realm of the retrograde moons, it's orbiting in the opposite direction to them. Researchers have proposed naming the "oddball" Valetudo, after the Roman goddess of health and hygiene.

Valetudo is more than just the odd moon out; it's also a serious collision hazard.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Because it's orbiting in the opposite direction of the nine "new" retrograde moons, and across their paths, there is a high risk that it will hit one of them, according to the statement.

"This is an unstable situation," Sheppard said. "Head-on collisions would quickly break apart and grind the objects down to dust."Some of Jupiter's moons and moon groupings, including the "oddball," could have formed from collisions like this, according to the statement.

While researchers aren't certain if this is exactly what happened, understanding how and when Jupiter's moons formed could help scientists to better understand the early solar system as a whole, the statement said.

For example, a large amount of gas and dust would push very small moons (moons between 1 and 3 kilometers (.6 and 1.9 miles) in diameter) toward their planet. This means that such gas and dust couldn't have been present when earlier, larger moons collided and created these small moons. So, by that logic, moons of that small size must have formed after the era of planet formation, a time when a disk of gas and dust swirled around the sun and formed planets, according to the statement.

Email Chelsea Gohd at cgohd@space.com or follow her @chelsea_gohd. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Chelsea Gohd joined Space.com as an intern in the summer of 2018 and returned as a Staff Writer in 2019. After receiving a B.S. in Public Health, she worked as a science communicator at the American Museum of Natural History. Chelsea has written for publications including Scientific American, Discover Magazine Blog, Astronomy Magazine, Live Science, All That is Interesting, AMNH Microbe Mondays blog, The Daily Targum and Roaring Earth. When not writing, reading or following the latest space and science discoveries, Chelsea is writing music, singing, playing guitar and performing with her band Foxanne (@foxannemusic). You can follow her on Twitter @chelsea_gohd.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus