Alexander the Great: Facts, biography and accomplishments

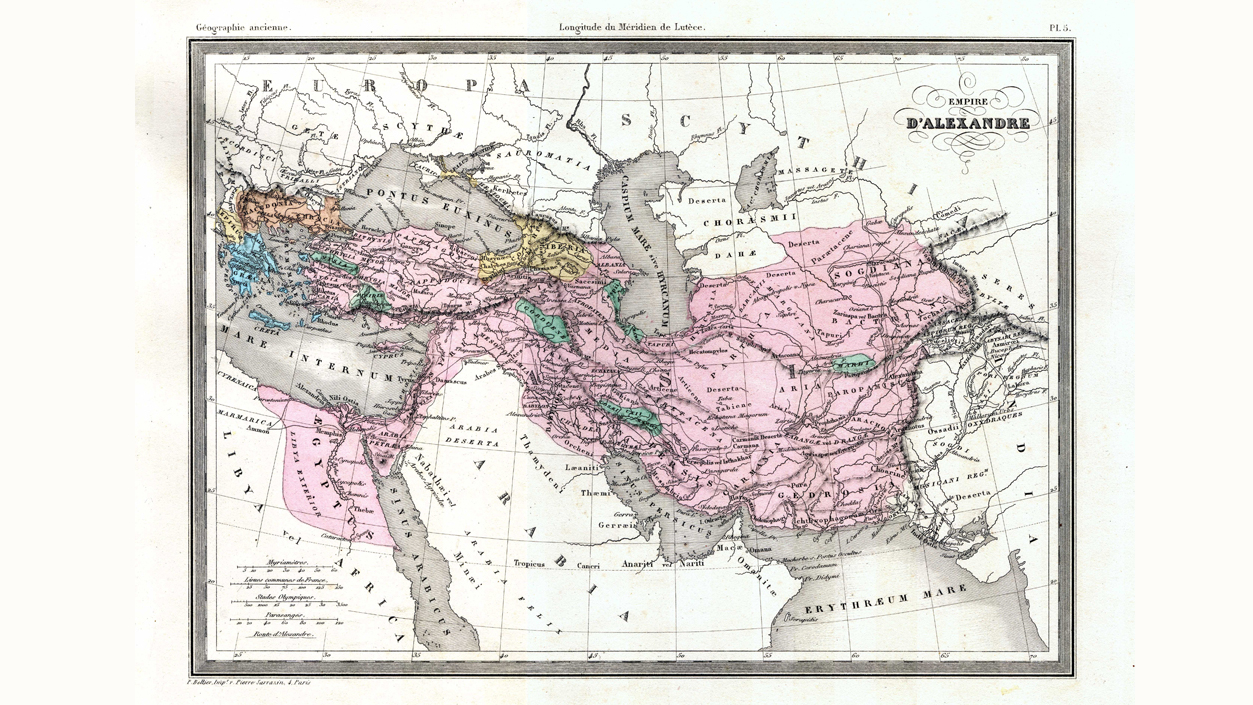

Alexander the Great's empire stretched from the Balkans to modern-day Pakistan.

Alexander the Great was king of Macedonia from 336 B.C. to 323 B.C. and conquered a huge empire that stretched from the Balkans to modern-day Pakistan.

During his reign, Alexander the Great had a massive impact in his time and sent ripples into the future. "In a reign of 13 years Alexander shot across the Greek and Middle Eastern firmament like a meteor, transforming whatever he — often brutally — touched and ensuring the ancient world and so eventually our world could never be the same again," Paul Cartledge, A.G. Leventis professor of Greek culture at Cambridge University, wrote in All About History magazine.

Alexander's triumphs also made him a legendary figure and an inspiration for future generations. "Until the internet age, Alexander the Great was probably the most famous human being who ever lived," Cartledge wrote. "His astounding career of conquest inspired not just Caesar and Augustus but also Mark Antony, Napoleon, Hitler and other would-be world conquerors from the West."

Related: Has the tomb of Alexander the Great's mom been found?

Yet, despite his military accomplishments, ancient records say that he failed to win the respect of some of his subjects, wrote Pierre Briant, emeritus professor of history at Collège de France, in "Alexander the Great and His Empire" (Princeton University Press, 2010) and, furthermore, he had some of the people closest to him murdered.

"The personality of Alexander the Great was a paradox," Susan Abernethy of The Freelance History Writer told Live Science. "He had great charisma and force of personality but his character was full of contradictions, especially in his later years (his early 30s). However, he had the ability to motivate his army to do what seemed to be impossible."

Where was Alexander the Great from?

Alexander was born around July 20, 356 B.C., in Pella in modern-day northern Greece, which was the administrative capital of ancient Macedonia. He was the son of King Philip II and Olympias (one of Philip's seven or eight wives) and was brought up with the belief that he was of divine birth. "From his earliest days, Olympias had encouraged him to believe that he was a descendent of heroes and gods. Nothing he had accomplished would have discouraged this belief," wrote Guy MacLean Rogers, a professor of classics at Wellesley College, Massachusetts, in his book "Alexander" (Random House, 2004).

Alexander's father was often away, conquering neighboring territories and putting down revolts. Nevertheless, King Philip II of Macedon was one of Alexander's most influential role models, Abernethy said. "Philip ensured Alexander was given a noteworthy and significant education. He arranged for Alexander to be tutored by Aristotle himself … His education infused him with a love of knowledge, logic, philosophy, music and culture. The teachings of Aristotle [would later aid] him in the treatment of his new subjects in the empires he invaded and conquered, allowing him to admire and maintain these disparate cultures."

Alexander watched his father campaign nearly every year and win victory after victory. Philip remodeled the Macedonian army from citizen-warriors into a professional organization, wrote Ian Worthington, professor of history and archaeology at Macquarie University, in "Philip II of Macedonia" (Yale University Press, 2010). Philip suffered serious wounds in battle, such as the loss of an eye, a broken shoulder and a damaged leg, according to Worthington.

Philip decided to leave his 16-year-old son in charge of Macedonia while he was away on campaign, Cartledge wrote in his book "Alexander the Great" (Overlook Press, 2004). Alexander took advantage of the opportunity by defeating a Thracian people called the Maedi and founding "Alexandroupolis," a city he named after himself.

"Alexander felt the need to challenge his father's authority and superiority and wished to out-do his father," Abernethy said.

Ancient records, such as Plutarch's "Lives," indicate that Alexander and Philip became estranged later in Alexander's teenage years. "Alexander may have resented his father's many marriages and the children born from them, seeing them as a threat to his own position," said Abernethy. At one point his mother Olympia was exiled to Epirus in western Greece.

Philip was assassinated in 336 B.C. while celebrating the wedding of his daughter Cleopatra (not the famous Egyptian pharaoh). The person who stabbed him was said to have been one of Philip's former male lovers, named Pausanias. While the ancient Greek historian Cleitarchus pointed to jealousy and betrayal as the motive, as outlined by Diodorus Siculus in "Library of History," other ancient sources like Justin in "Epitome of the Philippic History Of Pompeius Trogus" suspected that Pausanias may have been part of a larger plot to kill the king — one that may have included Alexander and his mother.

At the time of his death, Philip was contemplating invading the Persian Empire, also known as the Achaemenid Empire, which at its peak stretched from the Balkan peninsula to modern-day Pakistan and had repeatedly attempted to conquer the Greek world. Philip’s dream was passed onto Alexander, partly via his mother Olympias, according to Abernethy. "She fostered in him a burning dynastic ambition and told him it was his destiny to invade Persia."

Upon his father's death, Alexander moved quickly to consolidate power. He gained the support of the Macedonian army and intimidated the Greek city states that Philip had conquered into accepting his rule. After campaigns in the Balkans and Thrace, Alexander moved against Thebes, a city in Greece that had risen up in rebellion. He conquered it in 335 B.C. and had the city destroyed.

With Greece and the Balkans pacified, he was ready to launch a campaign against the Persian Empire.

Conquering the Persian Empire

While Alexander may have had his own reasons for expanding eastward, "his official reason for wanting to conquer the Achaemenid Persian Empire… was to lead the allied Greeks in a war of liberation: to free forever from Persian control the Greek cities along the Anatolian coast and on the island of Cyprus, and in so doing also to exact revenge for the Persians' invasion of Greece under Great King Xerxes in 480-479 BCE," Cartledge wrote.

But ironically, Alexander often fought Greek mercenaries while campaigning against Darius III, the king of Persia. Even more ironically, Sparta, a city that had famously lost its king and 300 warriors in the Battle of Thermopylae during a Persian invasion attempt, also opposed Alexander, going so far as to seek Persian help in the Spartans’ efforts to overthrow him, according to Siculus.

Nevertheless, Alexander was hugely successful against Persia. The first major battle he won against the Perisans was in 334 B.C. at the Battle of Granicus, fought in modern-day western Turkey, not far from the ancient city of Troy. The ancient Greek historian Arrian wrote that Alexander defeated a force of 20,000 Persian horsemen and an equal number of foot soldiers. He then advanced down the coast of west Turkey, taking cities and depriving the Persian navy of bases.

The second key battle he won — and perhaps the most important — was the Battle of Issus, fought in 333 B.C. near the ancient town of Issus in southern Turkey, close to modern-day Syria. In that battle, the Persians were led by Darius III himself. Arrian estimated that Darius had a force of 600,000 troops (probably wildly exaggerated) and initially positioned himself on a great plain where he could mass his force effectively against Alexander, who hesitated to give battle.

Darius is said to have thought this as a sign of timidity. "One courtier after another incited Darius, declaring that he would trample down the Macedonian army with his cavalry," Arrian wrote. So, Darius gave up his position and chased Alexander. At first this went well, and Darius’s soldiers got in the rear of Alexander's force. However, Darius’s army had been led to a narrow spot where the Persians could not use their superior numbers effectively, and at that point Alexander moved his force against the Persians. Alexander’s experienced army proved too strong for the Persian force, and eventually Darius fled, along with his army.

In his haste, Darius left much of his family behind, including his mother, wife, infant son and two daughters. Alexander ordered that they be "honored, and addressed as royalty," Arrian wrote. After the battle, Darius offered Alexander a ransom for his family and alliance, through marriage.

Arrian wrote that Alexander rebuked Darius in writing, saying "in the future whenever you send word to me, address yourself to me as King of Asia and not as an equal, and let me know, as the master of all that belonged to you, if you have need of anything."

Pharaoh of Egypt

Alexander then moved south along the eastern Mediterranean, continuing a strategy designed to deprive the Persians of their naval bases. Many cities surrendered, but some, such as Tyre, which was on an island in modern-day Lebanon, put up a fight and forced Alexander to lay siege.

In 332 B.C., after Gaza was taken by siege, Alexander entered Egypt, a country that had experienced on-and-off periods of Persian rule for two centuries. On its northern coast, he founded Alexandria, the most successful city he ever built. Arrian wrote that "a sudden passion for the project seized him, and he himself marked out where the agora was to be built and decided how many temples were to be erected and to which gods they were to be dedicated…".

Alexander claimed the title of pharaoh, and according to Cartledge, looked to attach himself to the line of Egyptian rulers through a traditional ceremony. "Almost certainly he had himself crowned pharaoh in the old Egyptian capital of Memphis, thereby not only ingratiating himself with the Egyptian masses but also enfolding the old and still powerful Egyptian priesthood in the embrace of his new Egyptian monarchy," Cartledge wrote.

Battle of Gaugamela

With the eastern Mediterranean and Egypt under his control, Alexander successfully deprived the Persians of naval bases and was free to move inland to conquer the eastern half of the Persian Empire.

At the Battle of Gaugamela, fought in 331 B.C. in northern Iraq near present-day Erbil, Alexander faced as many as 1 million troops, according to Arrian (modern scholars' estimates vary but put the total closer to 100,000 against roughly 50,000 soldiers for Alexander). Darius brought soldiers from all over his empire, and even beyond. Scythian horsemen from the Persian Empire’s northern borders faced Alexander, as did "Indian" troops (as the ancient writers called them) who were probably from modern-day Pakistan.

The battle soon became a war of nerves. "For a brief period the fighting was hand to hand, but when Alexander and his horseman pressed the enemy hard, shoving the Persians and striking their faces with spears, and the Macedonian phalanx, tightly arrayed and bristling with pikes, was already upon them, Darius, who had long been in a state of dread, now saw terrors all around him; he wheeled about — the first to do so — and fled," Arrian wrote. From that point on the Persian army started to collapse and the Persian king fled, with Alexander in hot pursuit.

Darius was later betrayed by one of his satraps, or regional governors, named Bessus (who then claimed kingship over what was left of Persia), and was killed by his own troops in 330 B.C.

Alexander wanted a peaceful transition of power in Persia following Darius’s defeat. He needed to have the appearance of legitimacy to appease the people, so Alexander provided a noble burial for Darius.

"[Providing noble burials] was a common practice by Alexander and his generals when they took over the rule of different areas of the empire," Abernethy said.

Alexander was influenced by the teachings of his tutor, Aristotle, whose philosophy of Greek ethos did not require forcing Greek culture on the colonized. "Alexander would take away the political autonomy of those he conquered but not their culture or way of life. In this way, he would gain their loyalty by honoring their culture, even after the conquest was complete, creating security and stability. Alexander himself even adopted Persian dress and certain Persian customs," Abernethy said.

Wishing to incorporate the most easterly portions of the Persian Empire into his own, Alexander campaigned in central Asia from 330 and 327 B.C. It was a rocky, frost-bitten conflict, which raised tensions within his own army, and led to Alexander killing two of his closest friends.

Why did Alexander kill his friends?

Alexander killing Parmenio, his former second in command, and Cleitus, the Macedonian king’s close friend who is said to have saved his life at the Battle of Granicus, may be seen as a sign of how Alexander’s men were becoming tired of campaigning, and how Alexander was becoming increasingly paranoid.

At some point during Alexander's campaign in central Asia, Parmenio's son, Philotas, allegedly failed to report a plot against Alexander's life. The king, incensed, decided to kill not only Philotas and the other men deemed conspirators, but also Parmenio, even though he apparently had nothing to do with the alleged plot.

According to the first-century A.D. writer Quintus Curtius (as found in "Alexander The Great: Selections from Arrian, Diodorus, Plutarch, and Quintus Curtius," Hackett Publishing, 1800), Alexander tasked a man named Polydamas, a friend of Parmenio, to perform the deed, holding his brothers hostage until he murdered Parmenio. Arriving in Parmenio's tent in the city where he was stationed, Polydamas handed him two letters: one from Alexander and one from Parmenio’s son.

When Parmenio was reading the letter from his son, a general named Cleander, who aided Polydamas with his mission, "opened him (Parmenio) up with a sword thrust to his side, then struck him a second blow in the throat…" killing him, Quintus Curtius wrote.

A second casualty of Alexander's fury was his friend Cleitus, who was angry at Alexander for adopting Persian dress and customs. After an episode where the two were drinking, Cleitus scolded the king, telling him, in essence, that he should follow Macedonian ways, not Persian customs.

Cleitus lifted up his right hand and said, "this is the hand, Alexander, that saved you then (at the Battle of Granicus)," according to Arrian. Alexander, infuriated, killed him with a spear or pike.

Alexander took his act of murder terribly. "Again and again, he called himself his friend's murderer and went without food and drink for three days and completely neglected his person," Arrian wrote.

Alexander's final battles

Alexander's days in central Asia were not all unhappy. After his troops had captured a fortress at a place called Sogdian Rock in modern-day Uzbekistan in 327 B.C. he met Roxana, the daughter of a local ruler. The two married, and they had an unborn son at the time of Alexander’s death.

Despite his men’s fatigue, and the fact that he was far from home, Alexander pressed on into a land that the Greeks called "India" (what is now present-day Pakistan). Plutarch explained in "The Life of Alexander the Great" that he made an alliance with a local ruler named Taxiles, who agreed to allow Alexander to use his city, Taxila, as a base of operations. He also agreed to give Alexander all the supplies he needed — which was very useful given Alexander's long supply lines.

In exchange, Alexander agreed to fight Porus, a local ruler who set out against Alexander with an army that reportedly included 200 elephants. The two armies met at the Hydaspes River in 326 B.C. Alexander bided his time; he scouted the area, built up a fleet of ships and lulled Porus into a false sense of security.

When Porus mobilized his forces he found himself in a predicament; his cavalry was not as experienced as Alexander's. As such, he put his 200 elephants — animals the Macedonians had never faced in large numbers — up front.

Alexander responded by using his cavalry to attack the wings of Porus's forces, quickly putting Porus's cavalry to flight. The result was that Porus's cavalry, foot soldiers and elephants eventually became jumbled together. Making matters worse for Porus, Alexander's soldiers attacked the elephants with javelins, and the wounded elephants went on a rampage, stomping on both Alexander and Porus's troops.

With his army falling apart, Porus stayed until the end and was captured. Arrian wrote that Porus was brought to the Macedonian king and said, "treat me like a king, Alexander." Alexander, impressed with his bravery and words, made him an ally.

The journey home

In 324 B.C., Alexander's close friend, general and bodyguard Haphaestion died suddenly from fever. Haphaestion's death caused a drastic change in Alexander's personality, Abernethy said. "Alexander had always been a heavy drinker and the substance abuse began to take its toll. He lost his self-control and his compassion for his men. He became reckless, self-indulgent and inconsistent, causing a loss of loyalty by his men and officers. He had always had a violent temper and been rash, impulsive and stubborn. The drinking made these traits worse."

Under such conditions, many of his men insisted that Alexander turn back home, according to Abernethy. Sailing south down the Indus River, he fought a group called the Malli and was severely wounded after he led an attack against their city wall. After reaching the Indian Ocean he split his force in three. One element, with the heavy equipment, would take a relatively safe route to Persia, the second, under his command, would traverse Gedrosia, a largely uninhabited deserted area that no large force had ever crossed before. A third force, embarked on ships, would support Alexander's force and sail alongside them.

The Gedrosia crossing was a miserable failure, and upto three-quarters of Alexander's troops died along the way. His fleet was unable to keep up with the main force due to bad winds. "The burning heat and the lack of water destroyed a great part of the army and particularly the pack animals," Arrian wrote.

Why Alexander chose to lead part of his force through Gedrosia is a mystery. It could simply be because no one had ever attempted to bring such a large force through it before and Alexander wanted to be the first.

Return to Persia and death

Alexander returned to Persia, this time as the ruler of a kingdom that stretched from the Balkans to Egypt to modern-day Pakistan. In 324 B.C., he arrived in Susa in present-day Iran, where a number of his innermost advisers got married.

Alexander got married to two other women, in addition to Roxana, whom he had married in central Asia. One was Barsine, daughter of Darius III, and the other was a Persian woman Arrian identified as Parysatis. Roxana likely did not take kindly to her two new co-wives and, after Alexander's death, she may have had them both killed, Plutarch wrote.

In 323 B.C., Alexander was in Babylon in modern-day Iraq, and his next major military target was apparently to be Arabia on the southern end of his empire. In June 323 B.C., while he was readying troops, he caught a fever that would not go away. He soon had trouble speaking and eventually died, with some suggesting he was poisoned. However, his death may have been announced prematurely, according Katherine Hall, a senior lecturer in the Department of General Practice and Rural Health at the University of Otago in New Zealand.

Shortly before his death, Alexander was supposedly asked who his empire should go to. His answer was said to be "to the strongest man," although he had an unborn son. However, there was nobody strong enough to hold his empire together. "Alexander's untimely death, without any provision having been made for a smooth succession (if such were indeed possible), opened the floodgates for two generations of warfare among his marshals, generals and lieutenants for their slice of his hypertrophied empire," Cartledge wrote.

Alexander's legacy

"Perhaps the most significant legacy of Alexander was the range and extent of the proliferation of Greek culture," Abernethy said. "The reign of Alexander the Great signaled the beginning of a new era in history known as the Hellenistic Age. Greek culture had a powerful influence on the areas Alexander conquered."

Many of the cities that Alexander founded were named Alexandria, including the Egyptian city that is now home to more than 4.5 million people. The many Alexandrias were located on trade routes, which increased the flow of commodities between the East and the West.

Alexander's legacy remains alive today, according to Cartledge, and is reimagined and reinterpreted by each generation; "There have been many Alexanders, as many as there have been observers, enemies, admirers, worshippers or serious students of the man, and hero, and god."

Additional reporting by Jessie Szalay, Live Science contributor, and Jonathan Gordon, Editor of All About History.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.