Philip Who? A Gallery of Mystery Bones

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The tombs of Alexander the Great's extended family, first excavated in the 1970s, are a perennial source of controversy and frustration in the archaeological community. The debate centers around two tombs: Tomb I, which held human remains but had been looted in antiquity; and Tomb II, which was filled with treasure and armor, as well as the burnt bones of a man and a woman.

Tomb II has been identified as the final resting place of Philip II, Alexander the Great's father. But that identification is hotly contested. Some archaeologists believe that the bones actually belong to Philip III Arrhidaeus, Alexander's half-brother and a short-lived figurehead king. Philip II, they say, may actually rest in the looted Tomb I.

The debate has become entrenched and politicized, given the famous names involved. The Macedonian tombs near the city of Vergina, where the bones were found, are a UNESCO World Heritage site. Any new research paper on the tombs is met with skepticism from the opposing faction. Some observers despair of ever finding the truth.

Article continues belowThe following images show the fragile bones and bone fragments around which this controversy swirls. Whether they belong to Philip II, Philip III, their wives or some other person, these bones represent the last physical link to ancient Macedonian royalty. [Read full story about the controversial bones]

Injured leg

The left leg of an adult male skeleton found in Tomb I at Vergina. The thigh bone (femur) and one of the bones of the lower leg (the tibia) are fused, and hole at the knee suggests a devastating penetrating injury. The injury matches some historical accounts of a leg wound suffered in battle by Philip II, the father of Alexander the Great. After the wound, Philip II limped until his death by assassination. (Photo Credit: Image Courtesy Javier Trueba)

Philip II

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In a paper published in the journal PNAS on July 20, 2015, researchers argue that this leg wound is the "smoking gun" identifying the male skeleton in Tomb I as Philip II. This artist's impression reveals how the fused bones would have set the king's leg in a permanent bent position. He could have walked, albeit with difficulty. (Photo Credit: Image Courtesy Arturo Asensio)

Male jaw

The lower jaw of an adult male found in Tomb I. This jaw may belong to Philip II, father of Alexander the Great. Philip II was assassinated by one of his bodyguards in 336 B.C., possibly as part of a complicated revenge plot involving several of the king's male lovers.

The story, as recorded by ancient historian Diodorus of Sicily, goes like this: Philip's bodyguard and lover Pausanias became jealous that the king was doting on another man (also, confusingly, named Pausanias). The first Pausanias taunted the second so much that he committed suicide.

In revenge, the second Pausanias' friend Attalus (uncle of one of Philip II's wives), got the first Pausanias drunk and had him sexually assaulted. Pausanias brought the matter to Philip II, who promoted him but did not punish Attalus. Pausanias then assassinated Philip II to avenge his own honor.

The tale may or may not be true. Scholars have suggested that Alexander the Great's mother, Olympias, may have been involved, and the king had no shortage of enemies. (Photo Credit: Image Courtesy Javier Trueba)

Cleopatra's jaw?

If the male bones in Tomb I do belong to Philip II, the female skeleton found in the tomb is almost certainly his wife, Cleopatra. She was a teenager when she wed Philip, and was his seventh known wife. Cleopatra gave birth to the couple's child just days before Philip was assassinated. Days after his death, Olympias killed the child in Cleopatra's lap, according to the Latin historian Justin. She then forced Cleopatra to hang herself. (Photo Credit: Image courtesy of Javier Trueba)

Whose legs?

The leg bones of the female skeleton found in Tomb I. Antonis Bartsiokas and colleagues, reporting in the journal PNAS on July 20, 2015, argue that these bones belong to Philip II's wife Cleopatra. She was a robust woman who stood about 5 feet 4 inches (165 centimeters), according to the measurement of these bones. (Photo Credit: Image courtesy of Antonis Bartsiokas)

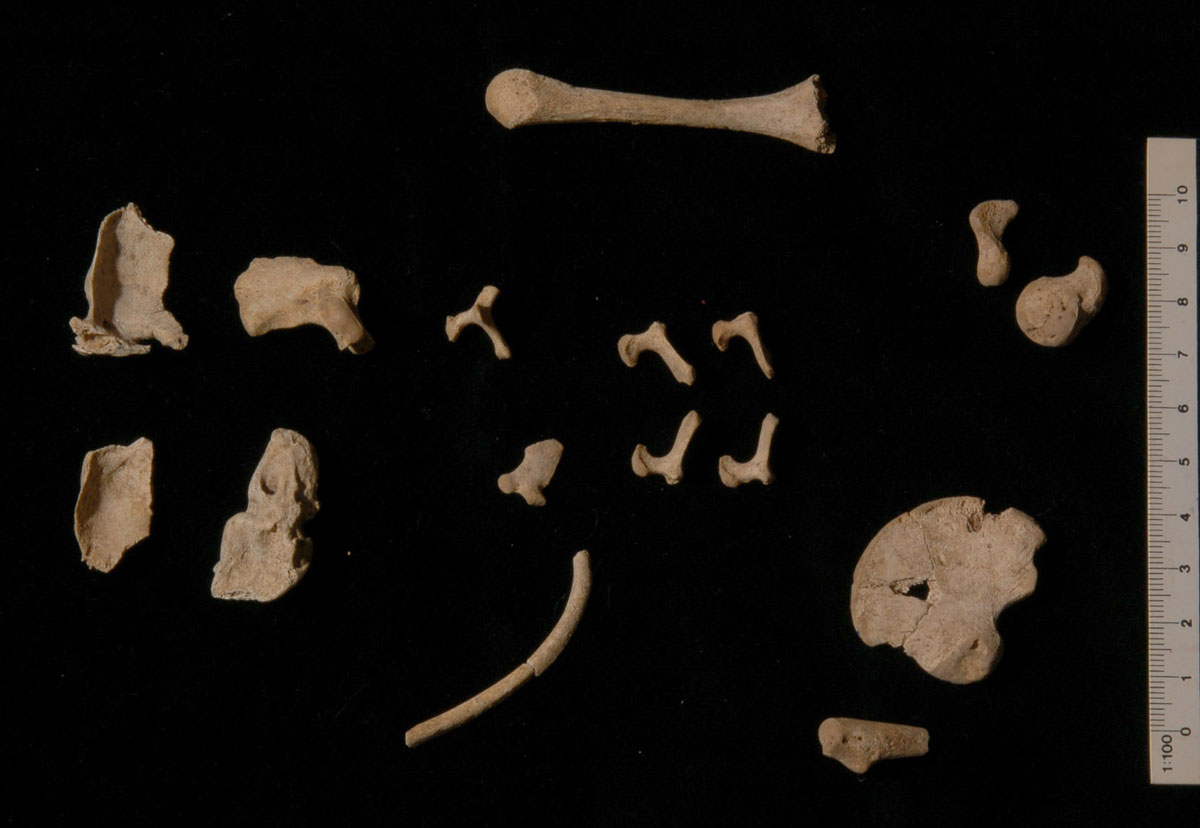

Teensy bones

Tiny newborn bones found in Tomb I belong to a child only one to three weeks past its due date. (It is impossible to know the baby's exact age, as it isn't clear from bones alone when an infant was born.) Anthropologists aren't sure of this infant's sex, but it may have been the murdered newborn child of Philip II and his seventh wife Cleopatra. (Photo Credit: Image courtesy of Antonis Bartsiokas)

An ancient mystery

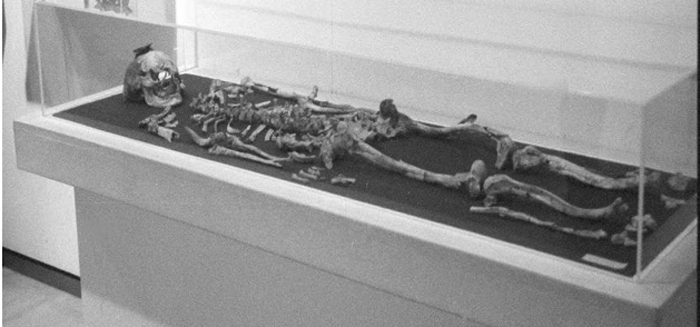

In 1977, archaeologists near Vergina, Greece, cracked open a lavish Macedonian tomb containing two skeletons. The grave goods made it clear that the researchers had discovered the royal resting place of relatives of Alexander the Great, the conqueror who created an empire spanning from Greece into modern-day India.

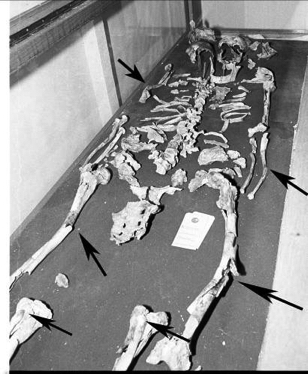

But the identity of the two skeletons remains hotly contested, even decades later. This male skeleton is likely to be either Philip II, Alexander the Great's powerful father, or Philip III Arrhidaios (also spelled Arrhidaeus), Alexander's reportedly feeble-minded half-brother. Philip II died in 336 B.C., and Philip III in 317 B.C. (Photo Credit: Jonathan Musgrave)

A mystery woman

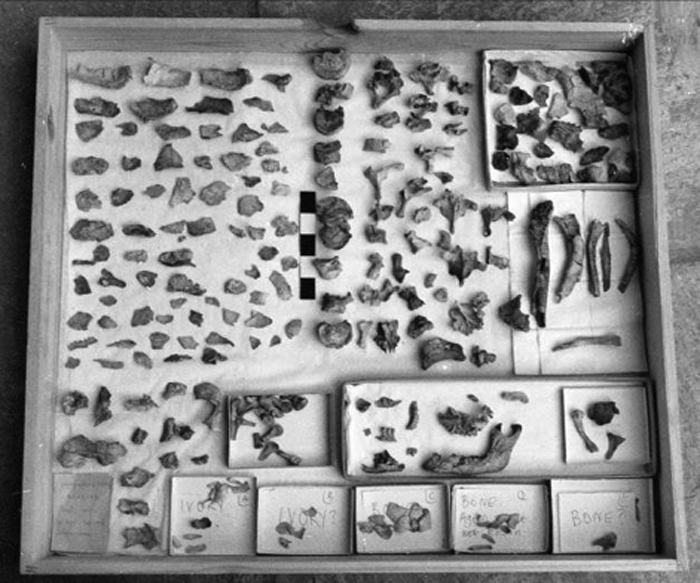

Alongside the male skeleton found in the tomb at Vergina were the burnt bones of a young woman. Her bone fragments fill two trays, one of which is seen here. The woman's identity is also unknown. If the tomb belongs to Philip III Arrhidaios, she is probably his wife, Eurydice. Intermarriage was common among ancient Macedonian royals, so Eurydice was also Philip III's niece (she was the daughter of Philip III's half-sister).

Philip II had somewhere in the range of seven wives. Archaeologists who believe the tomb is his have long suggested that the woman buried there is his last wife, Cleopatra (not the famous Egyptian queen, who lived centuries later). However, a study to be published in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology suggests that the woman could be another wife, name unknown, from the nearby kingdom of Scythia, which covered the area roughly where Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, most of Pakistan and some of Eastern Europe are today. (Photo Credit: Jonathan Musgrave)

A hot debate

A view of the male skeleton from the Vergina tomb. Over the years, much of the debate about the bones' identity has focused on whether they were cremated dry or with flesh still clinging to them. Philip III Arridaios was ordered executed by one of his father's wives, Olympias, in the succession wars that followed Alexander the Great's death. (Olympias was Alexander the Great's mother.) Eurydice was forced to commit suicide. According to ancient histories, the couple was then buried unceremoniously, only to be exhumed months, or perhaps more than a year, later for a royal burial to shore up legitimacy for the next king. At this royal burial, the bodies would have been cremated.

Philip II, on the other hand, would have been cremated right away. Thus, archaeologists reasoned, if the bones were cremated "fleshed," they were probably Philip II's. If they were cremated dry — the flesh having rotted off — they were probably Philip III's. But that line of thinking has been largely abandoned in recent years, given that a few months in the ground probably would have left Philip III Arridaios with some flesh still clinging to his bones. Thus, either body would have been cremated with flesh on. (Photo Credit: Jonathan Musgrave)

Proof of death

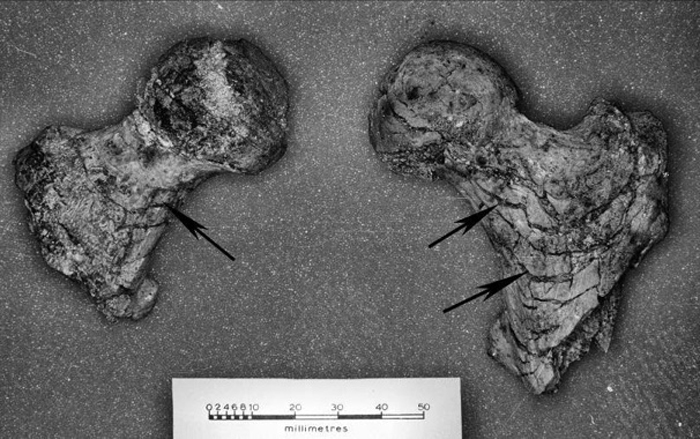

Fragments of the femoral (upper leg) bones from the woman in the Macedonian tomb. These pieces are the upper part of the femurs, and the knob is the joint where these bones connect to the pelvis. A 2010 article by University of Bristol anatomist Jonathan Musgrave noted the curved fractures in the bones and argued that these features indicated that the bones were burned with flesh still clinging to them. Bones warp differently in heat if burned dry versus burned with flesh on. (Photo Credit: Jonathan Musgrave)

Powerful woman

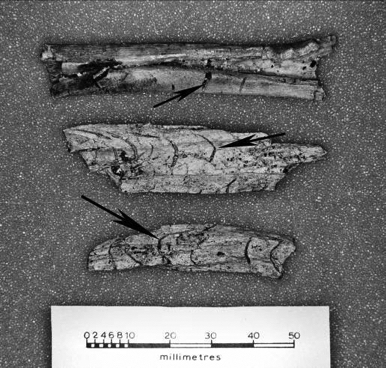

Limb bone fragments from the female skeleton found in the Vergina tomb. One candidate for the woman's identity is Eurydice II of Macedon, wife (and niece) of Philip III Arrhidaios. Eurydice was a warrior queen, as was her mother, Cynane (Alexander the Great's half sister). In the succession crisis that followed Alexander the Great's death, Cynane was determined to marry off her daughter to the new king, Philip III. In the process, Cynane was put to death by Alexander the Great's former generals, who were vying for power in the vacuum left by the conqueror's death. Eurydice, however, did marry Philip III and carried on her mother's ambitions, trying to grab real power for her figurehead husband. Ultimately, she led an army against the regent Polyperchon, but was stymied by the sudden appearance of Olympias, Alexander the Great's mother. Eurydice's troops refused to fight against the mother of Alexander the Great, who was backing Polyperchon, and she was forced to flee. She and her husband were both captured. He was executed, and she ordered to commit suicide by Olympias. (Photo Credit: Jonathan Musgrave)

Warped bones

This photograph of the male skeleton from Vergina was taken in 1983 at the Archaeological Museum in Thessaloniki, Greece. Arrows point to warping in the arm and leg bones caused by postmortem cremation. (Photo Credit: Jonathan Musgrave)

Debated facts

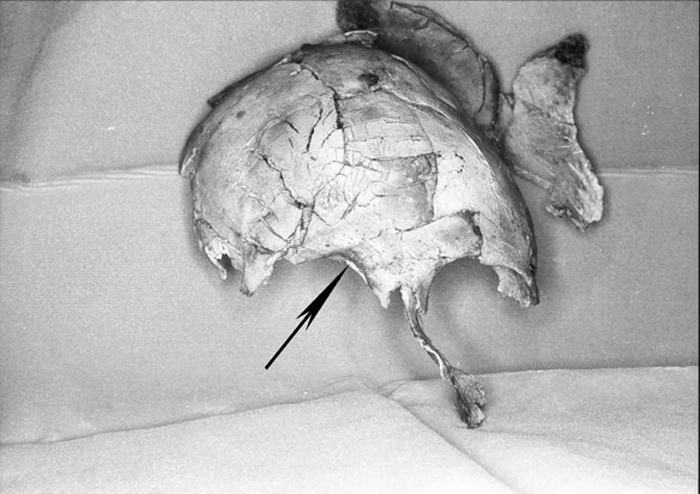

Part of the skull of the mystery male from Vergina. A large flange of bone is peeled outward, an effect of cremation. The question of whether these bones were burned dry or fleshed remains a contentious one: Musgrave argues that they were fleshed, while a 2000 paper in the journal Science by Antonis Bartsiokas, a paleoanthropologist at the Anaximandrian Institute of Human Evolution in Greece, argued that the bones were not warped enough to have been burned fleshed.

The debate may be the result of too little information, according to Maria Liston, an anthropologist at the University of Waterloo in Ontario who studies cremated remains in Greece. Not enough is known about how bones respond when cremated after partial decomposition of the body, as would have occurred with Philip III, Liston told Live Science in June. (Photo Credit: Jonathan Musgrave)

Battle scars?

A view of part of the skull of the male skeleton from Vergina. An arrow points to a notch in the eye socket that the University of Bristol's Musgrave interprets as a remnant of a known battle wound of Philip II's. However, a 2000 paper in the journal Science argued that this notch is an effect of postmortem handling and cremation. An upcoming study in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology also failed to find evidence of a pre-mortem eye wound — though those researchers did discover a healing hand fracture that could have matched one of Philip II's known injuries. (Photo Credit: Jonathan Musgrave)

Wounds or illness?

The jaw bone of the male skeleton from Vergina. The University of Bristol's Musgrave and Theodore Antikas of Aristotle University in Greece both noted, in separate studies, signs of inflammation in the jaw and sinuses of the skull. The inflammation could be the result of battle trauma, or chronic infection. For example, damage to the jaw could be caused by chronic gum disease. (Photo Credit: Jonathan Musgrave)

Dental work

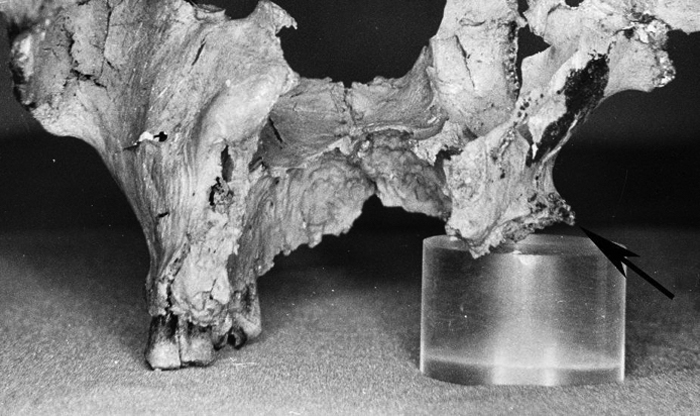

The remnants of the teeth and hard palate of the man buried in the Macedonian tomb at Vergina. The arrows show shallow molar sockets; when a tooth is removed, bone breaks down in the empty space in the jaw in a process called resorption. This process permanently changes the shape of the jaw bone. In the modern day, dentists use bone grafts or synthetic materials to preserve the socket after a tooth is removed, enabling them to place a false tooth later. (Photo Credit: Jonathan Musgrave)

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus