NASA: Arctic Meltdown Threatens Ice Cap's Stability

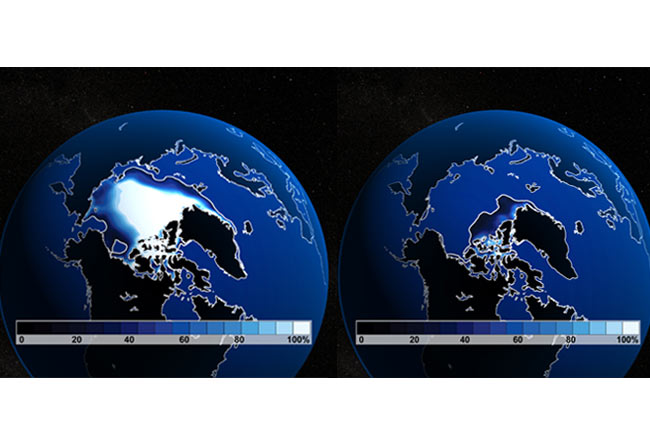

Perennial sea ice in the Arctic is melting faster each summer than it can be replaced during winter, a new study confirms.

A study released last year found that perennial sea ice—which is at least 10 feet thick and remains throught the seasons and through the years—dropped 14 percent from 2004 to 2005.

The new study, detailed today in a NASA statement, finds that the ice is not being replaced, threatening the overall stability of the Arctic summer ice cap, which other studies have predicted could disappear completely by 2040.

When perennial ice disappears, it is sometimes replaced by thinner seasonal ice, some of which melts the following summer.

"Recent studies indicate Arctic perennial ice is declining seven to 10 percent each decade," said Ron Kwok of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. "Our study gives the first reliable estimates of how perennial ice replenishment varies each year at the end of summer. The amount of first-year ice that survives the summer directly influences how thick the ice cover will be at the start of the next melt season."

Using satellite data from NASA's QuikScat and other data, Kwok studied six annual cycles of Arctic perennial ice coverage from 2000 to 2006. The scatterometer instrument on QuikScat sends radar pulses to the surface of the ice and measures the echoed radar pulses bounced back to the satellite. These measurements allow scientists to differentiate the seasonal ice from the older, perennial ice.

Kwok found that after the 2005 summer melt, only about four percent of the nearly 965,000 square miles of thin, seasonal ice that formed the previous winter survived the summer and replenished the perennial ice cover. That was the smallest replenishment seen in the study.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

As a result, perennial ice coverage in January 2006 was about 14 percent smaller than the previous January.

Ice can be depleted either by melting or by floating away. In 2005, the study found, the typically small amount of ice that moves out of the Arctic in summer was unusually high—about 7 percent of the perennial ice coverage area. Kwok said the high amount was due to unusual wind conditions at Fram Strait, an Arctic passage between Antarctic Bay in Greenland and Svalbard, Norway. Troughs of low atmospheric pressure in the Greenland and Barents/Norwegian Seas on both sides of Fram Strait created winds that pushed ice out of the Arctic at an increased rate.

The effects of ice movement out of the Arctic depend on the season. When ice moves out of the Arctic in the summer, it leaves behind an ocean that does not refreeze. This, in turn, increases ocean heating and leads to additional thinning of the ice cover.

These findings suggest that the greater the number of freezing temperature days during the prior season, the thicker the ice cover, and the better its chances of surviving the next summer's melt, according to the NASA statement.

"The winters and summers before fall 2005 were unusually warm," Kwok said. "The low replenishment seen in 2005 is potentially a cumulative effect of these trends."

Kwok also examined the 2000-2006 temperature records within the context of longer-term temperature records dating back to 1958. He found a gradual warming trend in the first 30 years, which accelerated after the mid-1980s.

"The record doesn't show any hint of recovery from these trends," he stated. "If the correlations between replenishment area and numbers of freezing and melting temperature days hold long-term, its expected the perennial ice coverage will continue to decline."

Kwok points to a possible trigger for the declining perennial ice cover. In the early 1990s, variations in the North Atlantic Oscillation, a large-scale atmospheric seesaw that affects how air circulates over the Atlantic Ocean, were linked to a large increase in Arctic ice export. It appears the ice cover has not yet recovered from these variations.

"We're seeing a decreasing trend in perennial ice coverage," he said. "Our study suggests that, on average, the area of seasonal ice that survives the summer may no longer be large enough to sustain a stable perennial ice cover, especially in the face of accelerating climate warming and Arctic sea ice thinning."

More to Explore

- Meltdown: Ice Cracks at North Pole

- 10 Surprising Results of Global Warming

- All About Global Warming

Global Warming Features

- Earth Will Survive Global Warming, But Will We?

- Strange Weather's Loose Link to Global Warming

- Global Warming or Just Hot Air? A Dozen Different Views

Recent Climate Change News

- Supreme Court Rebukes Bush on Carbon Dioxide Policy

- EU Presses United States on Global Warming

- Report Details Global Biological Change

- Charge: Carbon Dioxide Hogs Global Warming Stage

- Sun Blamed for Warming of Earth and Other Worlds

Hot Topic

What makes Earth habitable? This LiveScience original video explores the science of global warming and explains how, for now, conditions here are just right.

The Controversy

- Sun Blamed for Warming of Earth and Other Worlds

- World's Largest Science Group Chimes in on Climate Change

- 113 Nations Agree ... Climate Change 'Very Likely' Caused by Humans

- White House Accused of Misleading Public on Global Warming

- Global Warming or Just Hot Air? A Dozen Different Views

- Report: Global Warming's Smoking Gun is on the Table

- Global Warming Differences Resolved

- Baffled Scientists Say Less Sunlight Reaching Earth

- Scientists Clueless over Sun's Effect on Earth

- Greenhouse Gas Hits Record High

- Key Argument for Global Warming Critics Evaporates

The Effects

- Seas Rise

- More Wildfires

- Deserts to Grow

- Greenland Melts

- Mountains Grow

- Ground Collapses

- Glaciers Disappear

- Allergies Get Worse

- Summer Gets Longer

- Animal DNA Changing

- Animals Change Behavior

- Rivers Melt Sooner in Spring

- Increased Plant Production

- Hurricanes Get Stronger

- Some Trees Benefit

- Lakes Disappear

The Possibilities

- More Rain but Less Water

- Ice-Free Arctic Summers

- Overwhelmed Storm Drains

- Worst Mass Extinction Ever

- A Chilled Planet

Strange Solutions

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus