Double First: 19th-Century Book Is 1st with Photos, by 1st Female Photographer

The Rijksmuseum in the Netherlands recently announced their acquisition of a photography first: the first book to be illustrated with photos, by a British botanist widely recognized as the first woman to experiment with photography.

Their copy of "Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions," by Anna Atkins (1799-1871), is a rare edition of the 19th-century botanical volume, which Atkins self-published in 1844.

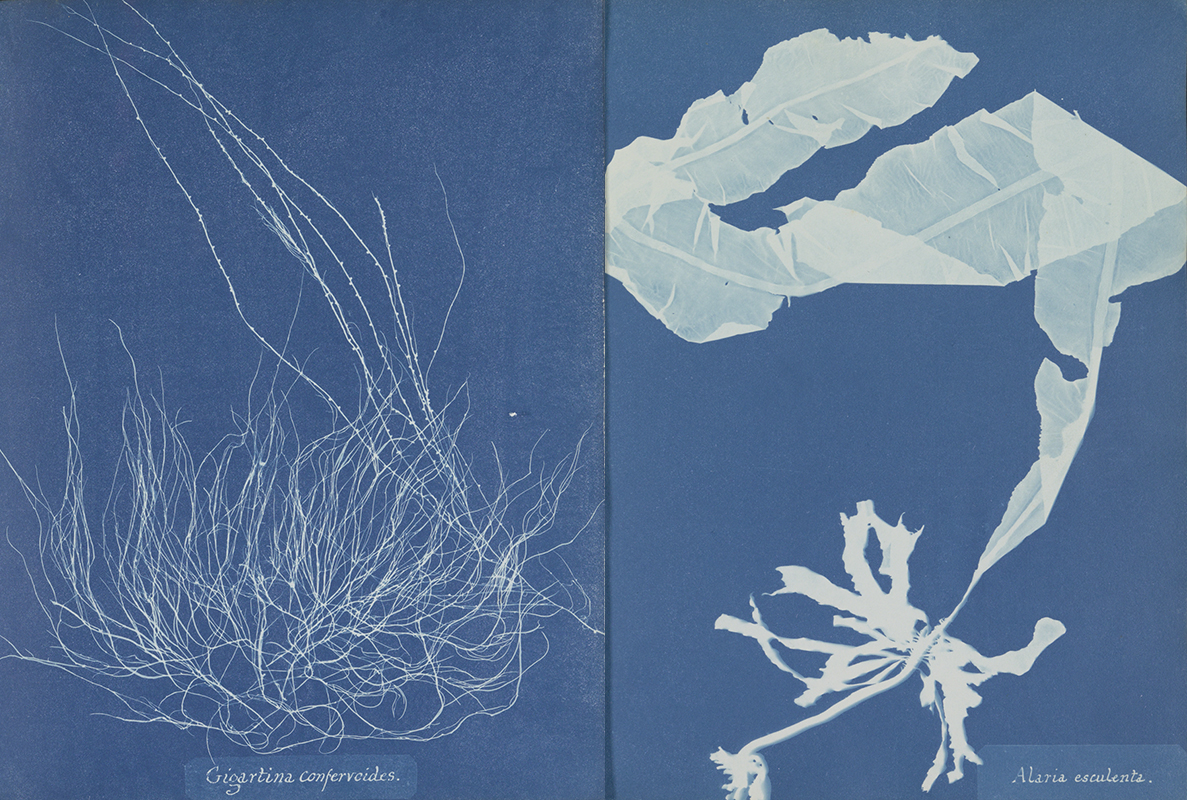

The book, which contains 307 images of algae native to waters in and around Great Britain, was the first to be illustrated with cyanotypes. This early form of photographic printing, also known as a "blueprint," was discovered in 1842 and uses chemicals and sunlight to create a negative image of an object silhouetted against a blue background. Atkins produced several editions of "Photographs of British Algae," of which about 20 copies — complete and incomplete — survive today, Rijksmuseum officials said in a statement. [Plant Photos: Amazing Botanical Shots by Karl Blossfeldt]

"Anna Atkins' work sits on the border between art and science," museum representatives said in the statement. Apart from their "historical significance, Atkins' images are characterized by their timeless beauty, which looks contemporary because of the abstraction of the silhouettes on the photographic paper."

The book will be featured in an upcoming Rijksmuseum exhibit, "New Realities: Photography in the 19th Century," open June 17 through Sept. 17, 2017, according to the statement. [See Gorgeous Photos of the Cyanotypes]

Cyanotypes were created by treating paper with ferric ammonium citrate and potassium ferricyanide — iron salts that dissolve in water — and then placing an object on the paper and exposing it to sunlight. The process forms the compound called Prussian blue. When the paper is washed, the spots untouched by the object (and so treated with iron salts) turn a shade of deep blue, the New York Public Library (NYPL) Digital Collections explained in a description of "Photographs of British Algae" published on the library's website.

Atkins learned about cyanotypes from her father, a scientist whose Royal Society associates discovered the process, and she quickly realized that this technique perfectly suited her needs for capturing detailed images of delicate water plants.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The difficulty of making accurate drawings of objects as minute as many of the Algae and Confera, has induced me to avail myself of Sir John Herschel's beautiful process of Cyanotype, to obtain impressions of the plants themselves," Atkins wrote in October 1843, in the introduction to her book.

She produced thousands of algae cyanotypes for the multiple editions of her book — a project that took 10 years, according to Rijksmuseum officials. The museum purchased the tome from a private owner for 450,000 euros ($50,3478), museum officials said.

While the public will be able to admire the historical volume as part of the Rijksmuseum exhibit, visitors won't exactly be able to flip through the work's pages. For those who want a closer look at all 307 of the book's stunningly beautiful cyanotypes, a scanned copy of "Photographs of British Algae" is available online at the NYPL Digital Collections website.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.