Scientists Find 8 New Species of Spider with Whiplike Legs

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

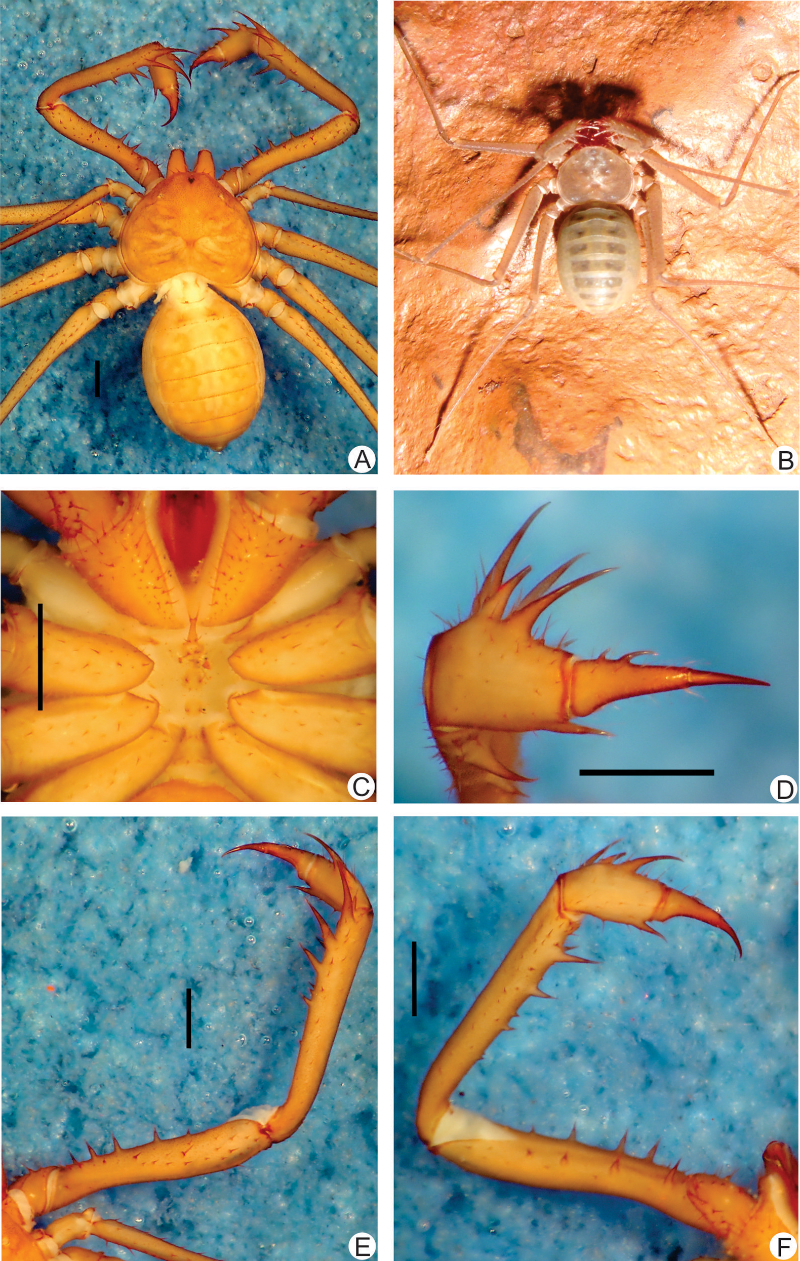

A pair of elongated, whiplike legs that are actually sophisticated environment sensors distinguish an unusual arachnid known as the whip spider, also called the tailless whip scorpion. Scientists recently described eight new species of this long-legged spider that are native to Brazil, nearly doubling the number of known species in the genus Charinus.

Whip spiders use only six of their eight legs for walking, reserving their "whips" — which can reach several times the spiders' body length — for exploring the world around them and locating prey, through a combination of touch and chemical signals.

Thanks to the new species discoveries, Brazil now boasts the greatest diversity of whip spiders in the world. But the forest ecosystems where these new species live are threatened by human development, and the researchers suggested that stronger conservation measures are urgently required in order to protect the whip spiders' habitats, and to discover more species before their habitats are destroyed. [Ghoulish Photos: Creepy, Freaky Creatures That Are (Mostly) Harmless]

There are 170 known species of whip spiders found all over the world, mostly in tropical areas in the Americas. According to the researchers, the Amazon region — known for its diverse habitats, plants and animals — was long suspected of hiding many more whip spider species than were previously known. Though some whip spiders measure up to 10 inches (25 centimeters) at the fullest extension of their "whips," most are less than 2 inches (5 cm) and are hard to spot, hiding in leaf litter, under stones and tree bark, and in caves.

To identify the new species, the researchers turned their attention to specimens from the collections in four Brazilian natural history museum collections: the Butantan Institute, the National Museum of Brazil, the Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, and the Museum of Zoology of the University of São Paulo.

What does it take to describe a new whip spider species? Days, weeks and ultimately months of scrutinizing the spiders' body parts under a microscope and comparing them with other known species in order to find unique and differentiating characteristics, said study co-author Gustavo Silva de Miranda.

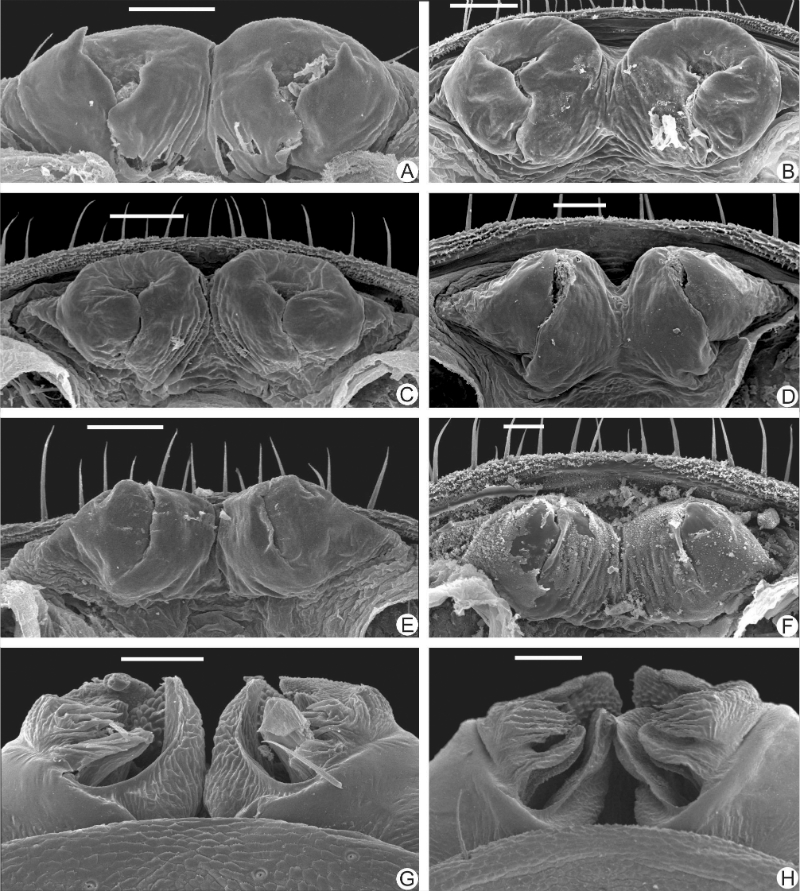

De Miranda, a graduate student at the Center for Macroecology, Evolution and Climate at the University of Copenhagen, told Live Science that he and his colleagues performed exhaustive inventory of the spiders' features, including the number of segments in the whiplike limbs, the prey-catching spines at the tips of their legs, the groupings of their eyes, and the shape of the females' genitalia, called gonopods.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"If we compare all these things and see that it's very unique, then we consider it a new species," de Miranda said.

Genital structures turned out to be quite an important point of comparison, de Miranda explained. In each whip spider species, the female's gonopod shape corresponded very specifically to the shape of the male's sperm sac, for perfect alignment.

But even as new whip spider species are described, their behavior and habits in the wild remain elusive, de Miranda said. One study, he said, detailed confrontations between males competing for females or territory — the spiders extend and display their head appendages, squaring off without actually fighting, and the loser (the one with the smaller display) retreats after a 20-minute stare-down.

"But there is still a lot to be discovered," de Miranda said. "We're trying to understand the evolution of the group, their relationships, how they are so widespread, their morphological evolution." He said this makes it imperative not only to find new species, but to preserve the fragile ecosystems where these spiders live.

"If they are not protected, they will vanish from nature," de Miranda said.

The findings were published online today (Feb. 17) in the journal PLOS ONE.

Follow Mindy Weisberger on Twitterand Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus