How Two Women Brought a Sea Change to Conservation (Op-Ed)

Madeleine Thompson is archivist for the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS).This article is the fourth and final blog in a series celebrating the contributions of women to the practice of conservation. Thompson contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

When renowned Bronx Zoo naturalist William Beebe added Gloria Hollister and Jocelyn Crane to his research staff nearly a century ago, his decision to employ two female scientists was considered novel enough that it required some justification. The zoo's founding ornithology curator went out of his way to acknowledge that he didn't care whether they were men or women. What mattered most in a researcher, said Beebe, is "what is above the ears."

Hollister arrived in 1928 with a master's in zoology and three years' experience in cancer research at Rockefeller University. Crane, who joined in 1930 after earning her bachelor's in zoology, had already published in the prestigious Journal of Mammalogy. Yet despite their qualifications — which paralleled those of their male colleagues — some media focused more on the women's sex than their science.

The same 1932 article that printed Beebe's praise for "what is above the ears" couldn't help noting that "both young women have sleek permanent waves above the ears, incidentally, and complete and very feminine wardrobes, including formal dresses for parties at the Governor's House in Bermuda."

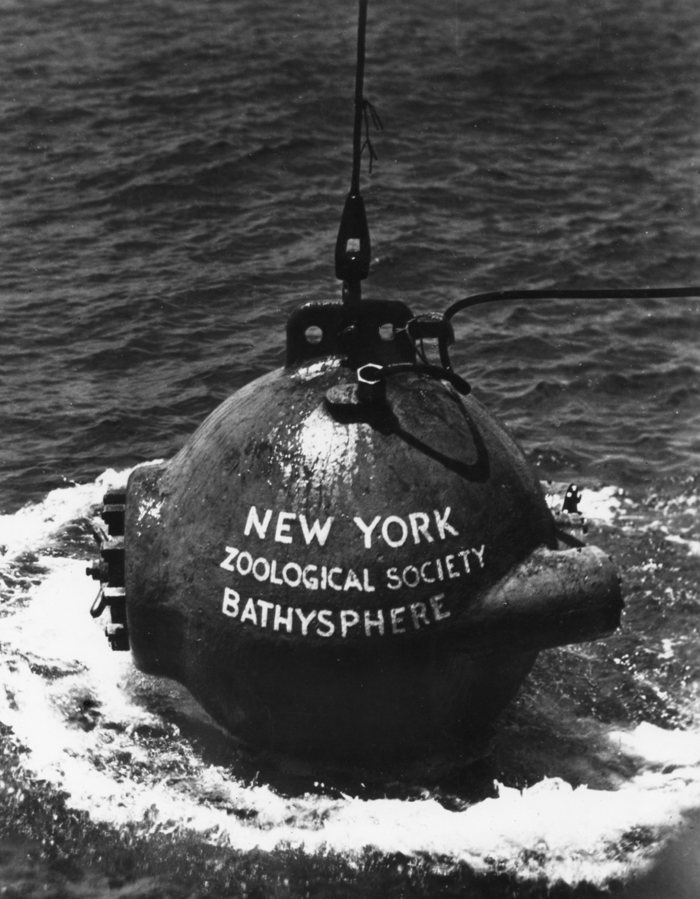

In spite of the attention to their physical appearance and the fact that the vast majority of their colleagues were men, Hollister and Crane forged significant scientific careers. An early focus on deep-sea ecology followed perhaps naturally from Beebe's explorations of the ocean off Bermuda in a bathysphere — a round submersible in which he and its designer, Otis Barton, made a series of record-setting dives in the 1930s.

At the time, Hollister served as chief technical associate for the Department of Tropical Research (DTR) of the New York Zoological Society (now the Wildlife Conservation Society). She developed a new technique for preparing fish specimens in which the skin and internal organs of the fish were made transparent, rendering their skeletons far more suitable for study than under previous methods.

She detailed this new approach in the NYZS technical publication, Zoologica. Describing it further for the lay readership of the organization's Bulletin, she explained that the method had so fascinated some of the Bermudians who observed it in the DTR lab that they dubbed it "fish magic."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Hollister achieved another feat in 1934 when she set the record for the deepest descent underwater by a woman, traveling 1,208 feet beneath the ocean surface in the bathysphere. Two years later, she led an expedition through Guyana to the Kaieteur Falls, studying the golden frog and the elusive hoatzin along the way.

Jocelyn Crane likewise moved on from ocean exploration. Her research ranged from the mammals of Kurdistan to jumping spiders in Venezuela. By the early 1940s, she had begun to concentrate her investigations on the genus Uca, exploring the morphology, taxonomy and behavior of a small but fascinating creature: the fiddler crab. It would define her career.

In a 1941 Bulletin article, she rhapsodized on the beauty of mating fiddler crabs, which she compared to "graceful dancers" that "would have done credit to the Russian ballet." She admitted that, in studying the crabs , she found it difficult to consider them "with that beautiful abstraction with which all self-respecting scientists are supposed to observe their non-human companions on this planet." In her careful observations, Crane divined moods and personalities.

In 1954, as an early recipient of funding from the U.S. National Science Foundation, she traveled through Asia conducting fiddler-crab research that led two decades later to her monumental "Fiddler Crabs of the World" (Princeton University Press, 1975), the pre-eminent study of the genus Uca.

In tandem with their research achievements, both Hollister and Crane made other lasting marks in conservation history. After resigning from the DTR to join the American Red Cross upon the start of World War II, Hollister led the campaign to preserve the Mianus River Gorge in New York, the original land project of The Nature Conservancy.

Crane continued to work with the DTR, rising to the position of assistant director in 1952 and then director upon Beebe's death in 1962. In 1965, she joined the staff of the Institute for Research in Animal Behavior, one of the forerunners to the Wildlife Conservation Society's current global conservation program.

This Women's History Month, we salute Gloria Hollister and Jocelyn Crane, two pioneering and inspiring figures whose early contributions to ecological field research continue to influence the work of wildlife conservationists today.

This article is the fourth in the series "Women's History Month: Blogs from the Wildlife Conservation Society." Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google +. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.

Other articles in the series include:

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus