'Goddess of dawn': James Webb telescope spies one of the oldest supernovas in the early universe

An extremely early Type II supernova explosion, named after the Titan goddess of dawn in Greek mythology, occurred just 1 billion years after the Big Bang.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Scientists have spotted a distant supernova unleashed by a collapsing star just 1 billion years after the birth of the universe.

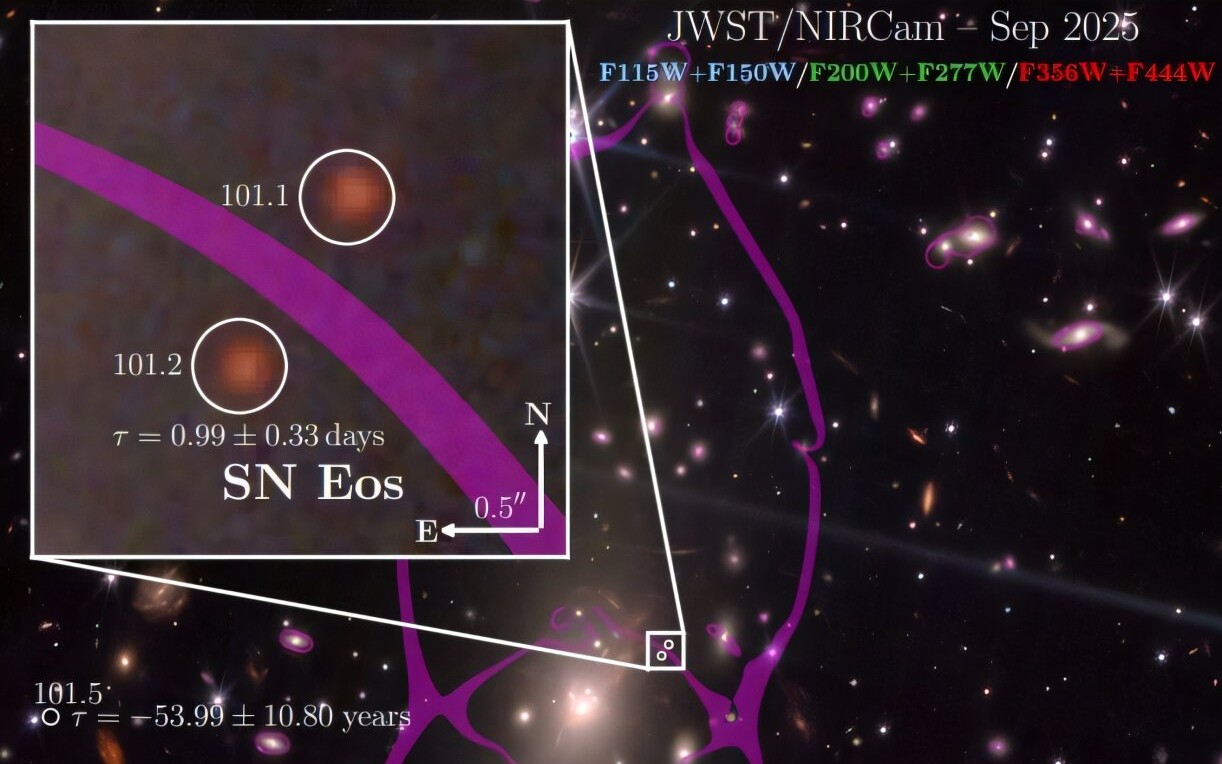

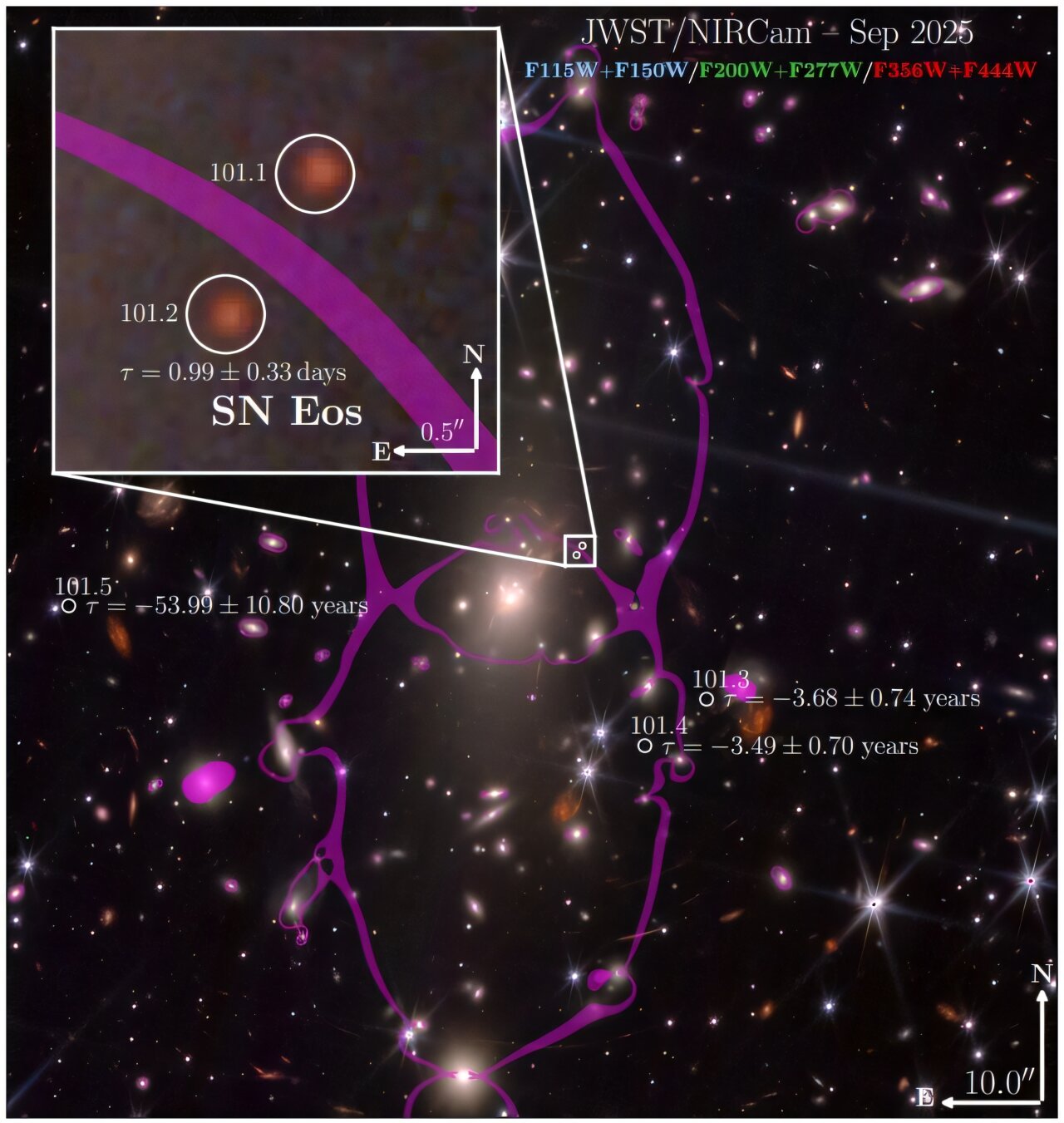

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) captured images of the Type II supernova on Sept. 1 and Oct. 8, 2025. Dubbed "Eos," after the Titan goddess of dawn in Greek mythology, the supernova will help scientists understand how stars and galaxies evolve over billions of years, researchers reported Jan. 7 on the preprint server arXiv.

A better understanding of early stars could help astronomers map out how those stars formed and distributed heavy elements, including those necessary for life, to their surroundings. But observing individual stars from the early universe is no easy feat.

"Due to their extreme distances, the opportunities to study such stars remain quite limited," the researchers wrote in the study, which has not been peer-reviewed yet. "However, the explosive deaths of massive stars as core-collapse supernovae, which can be brighter than the total emission of their host galaxies, allow us to probe the final stages of stellar evolution."

Deaths of the earliest stars

A supernova occurs when a massive star explodes at the end of its life. Type I supernovas include those that have no hydrogen in their spectra, while Type II supernovas show some evidence of hydrogen. Regardless of the type, supernovas aren't very common; just two to three occur per century in galaxies the size of the Milky Way.

In the new study, scientists used a phenomenon known as gravitational lensing to capture images of the distant supernova. Gravitational lensing occurs when light passes through an area of space-time that's been warped by the immense gravity of a massive object, such as a black hole or galaxy cluster. The distortion magnifies that light, allowing scientists to spot objects that would be too dim to see otherwise.

The supernova was rich in hydrogen, and its star exploded in an environment that held a very low concentration of elements heavier than hydrogen. In fact, the progenitor star likely had less than 10% of these heavier elements than our own sun does, the team found. This apparent lack of heavy elements further confirms the supernova's extremely early age, as stellar fusion had yet to fill the universe with plentiful heavy elements.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

By analyzing the ultraviolet light from the burst, the researchers determined that Eos is a Type II-P supernova. The light from a Type II-P supernova remains bright for a while after it peaks, before slowly fading out. (In contrast, Type II-L supernovas dim steadily over time.) Eos is likely near the end of its brightness plateau, the team found.

Scientists still need to observe more early supernovas to confirm if Eos' properties are typical for massive stars and supernovas of the epoch. But those findings could help scientists chart the evolution of stars and galaxies from the early universe to today.

"The discovery of SN Eos represents a critical step toward fulfilling JWST's core mission objectives of understanding the lives and deaths of the first stars, the origins of the elements, and the assembly and evolution of the youngest galaxies," the researchers wrote.

Skyler Ware is a freelance science journalist covering chemistry, biology, paleontology and Earth science. She was a 2023 AAAS Mass Media Science and Engineering Fellow at Science News. Her work has also appeared in Science News Explores, ZME Science and Chembites, among others. Skyler has a Ph.D. in chemistry from Caltech.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus