What is Lake Vostok?

Lake Vostok is one of the largest subglacial lakes in the world.

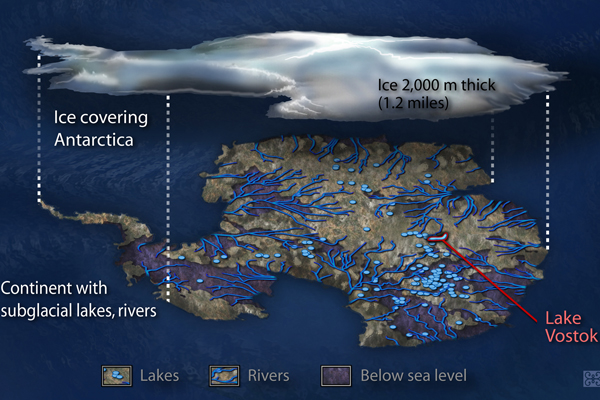

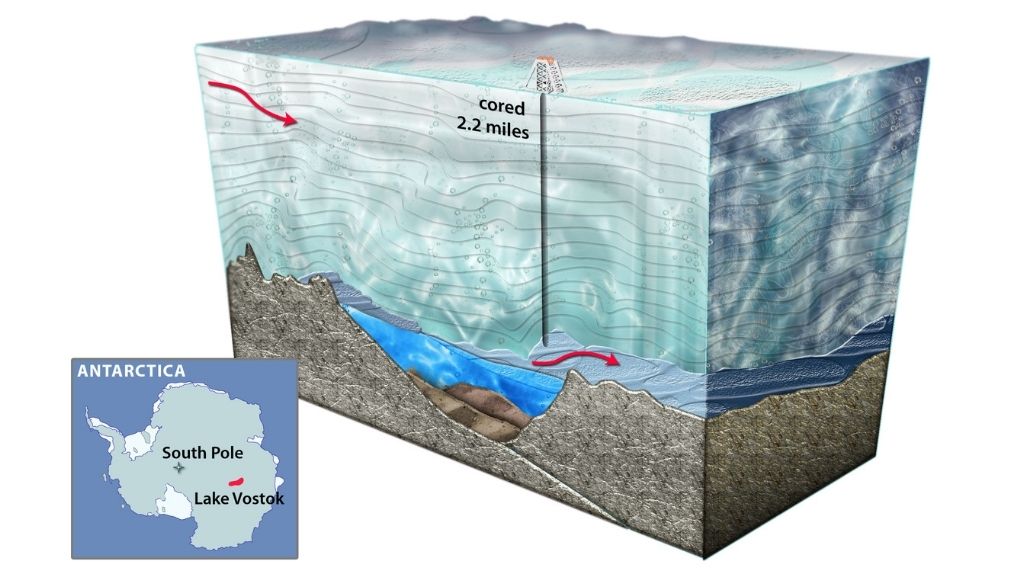

Deep, dark and mysterious, Lake Vostok is one of the largest subglacial lakes in the world. Once a large surface lake in East Antarctica, Lake Vostok is now buried under about 2.5 miles (4 kilometers) of ice near Russia's Vostok research station. Covered with ice for millennia, cut off from light and contact with the atmosphere, the lake is one of the most extreme environments on Earth, Live Science previously reported.

"The lake has been ice-covered for at least 15 million years," said Brent Christner, a Louisiana State University biologist who has examined ice cores collected above the lake. Some estimates suggest the lake has been covered with ice for up to 25 million years, according to NASA.

Related: Stunning photos of Antarctic ice

Below the surface

Lake Vostok is one of the largest freshwater lakes on Earth in size and volume, rivaling Lake Ontario in North America, according to NASA. The lake is roughly 149 miles (240 km) long and 31 miles (50 km) wide, and hundreds of meters deep, according to a blog authored by glacial scientist Bethan Davies. The south end of the lake may be up to 0.6 miles (1 km) deep, but the northern and southwest corners are comparatively shallow, Davies said.

The presence of a large buried lake was first suggested in the 1960s by a Russian geographer and pilot who noticed the large, smooth patch of ice above the lake from the air. But it wasn't until 1993, when scientists used satellite-based radar to survey the area, that scientists confirmed the subglacial lake's presence, Science reported.

"Lake Vostok is one of the easiest subglacial lakes to detect due to its size," Christner told Live Science. "[Yet] I believe most of its secrets remain."

The lake's only water supply is meltwater from overlying ice sheet, Christner said. "To my knowledge, there is no evidence for influx or efflux of water from Lake Vostok," he said. This constant replenishment from melting ice means the water in the lake may be relatively young, just thousands of years old, according to ice core studies. But the true age of the lake water is unknown, he said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

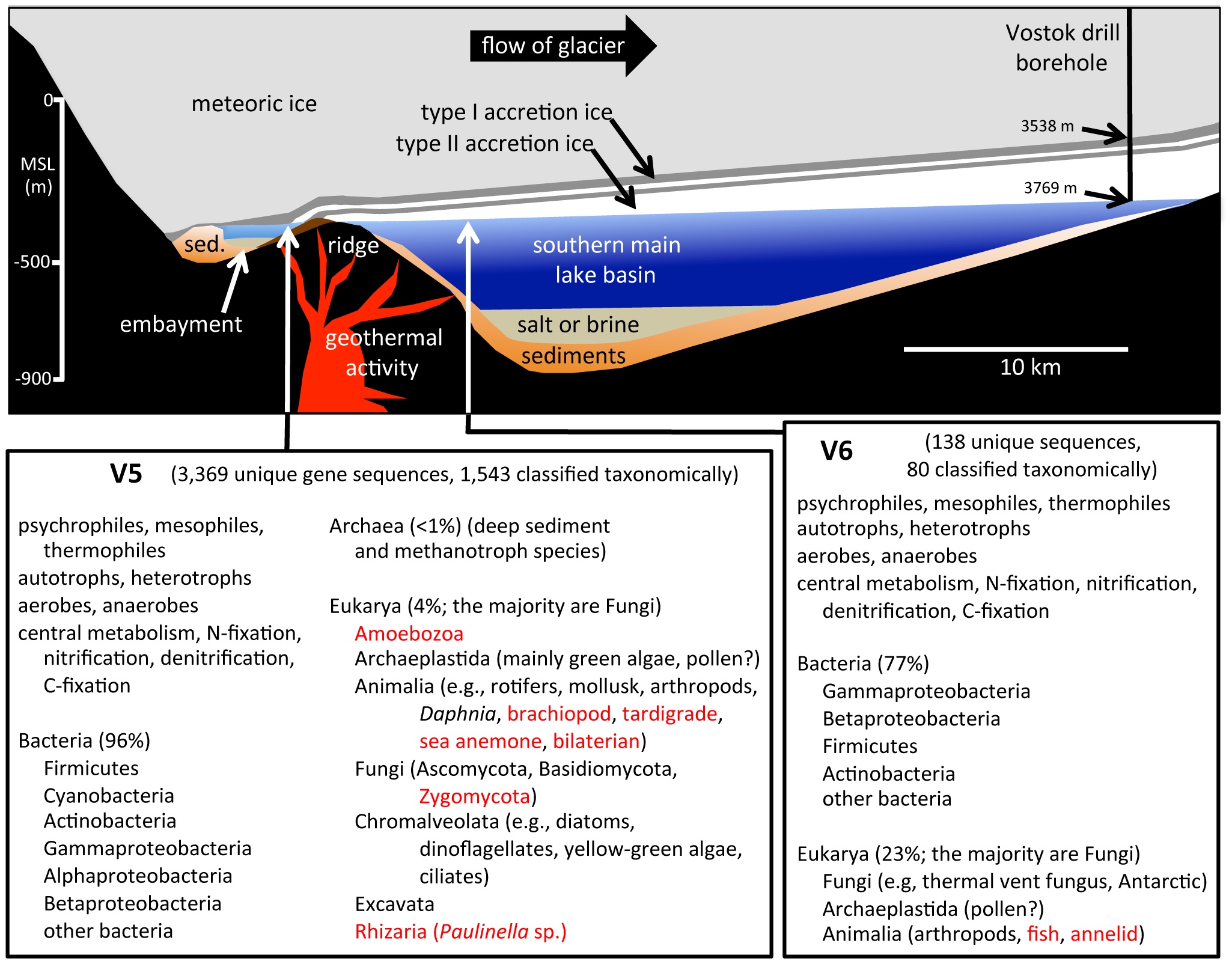

Researchers have mapped Lake Vostok's shape with remote-sensing techniques, such as seismic soundings and ice-penetrating radar. The deep and shallow regions of the lake are separated by a ridge. Some scientists think the ridge could be a hydrothermal vent, similar to the ocean floor black smokers that are known to teem with tubeworms, Popular Science reported. The long, narrow lake may lie in a rift valley, similar to Lake Baikal in Russia.

Related: Incredible technology: How to explore Antarctica

Geothermal heat from the Earth keeps the temperature of the lake water hovering around 27 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 3 degrees Celsius), according to a 2001 review article in the journal Nature. The weighty pressure of the overlying ice changes the melting point of water and keeps the lake liquid despite its below-freezing temperatures, according to World Atlas.

Life in the lake

In the 1990s, Christner was part of an international team that discovered microbes in frozen lake water collected above Lake Vostok's liquid surface, called accretion ice. The top half-inch (1 centimeter) of the lake surface freezes onto the flowing ice sheet above the lake.

Analysis of the life forms suggests Lake Vostok may harbor a unique ecosystem based on chemicals in rocks instead of sunlight, living in isolation for hundreds of thousands of years, Live Science previously reported. "The types of organisms we found suggested they derived their energy from minerals present in the lake and sources from the underlying bedrock," Christner said.

More recent studies of genetic material in Vostok's accretion ice revealed snippets of DNA from a wide variety of organisms related to single-celled creatures found in lakes, oceans and streams, Live Science previously reported. These "extremophiles" could mimic life on other moons and planets, such as Jupiter's icy moon Europa.

Related: Image gallery: Alien life of the Antarctic

In a paper published June 26, 2013, in the journal PLOS One, researchers, led by Scott Rogers, a Bowling Green State University professor of biological sciences, discussed the thousands of species they identified in Lake Vostok through DNA and RNA sequencing.

The researchers took samples from two areas of the lake: the southern main basin and near an embayment on the southwestern end of the lake.

By sequencing the DNA and RNA taken from samples of accretion ice (frozen lake water attached to the bottom of the overriding glacier), the team discovered far more complexity than anyone thought, Rogers said in a press release.

"It really shows the tenacity of life, and how organisms can survive in places where a couple dozen years ago we thought nothing could survive," he said.

In addition to fungi and two species of archaea, which are single-celled organisms that often live in extreme environments, the researchers identified thousands of bacterial species, including some that are commonly found in the digestive systems of fish, crustaceans and annelid worms, according to the press release.

They also discovered psychrophiles, or organisms that live in extreme cold, and heat-loving thermophiles, which suggests the presence of hydrothermal vents deep in the lake.

"Many of the species we sequenced are what we would expect to find in a lake," said Rogers. "Most of the organisms appear to be aquatic (freshwater), and many are species that usually live in ocean or lake sediments."

Rogers notes that the presence of both marine and freshwater species supports the theory that the lake once was connected to the ocean, and that the freshwater was supplied by the overriding glacier. The embayment contained the most biological activity with the largest number of species identified.

After two years of computer analysis, the team determined that Vostok Lake contains a diverse set of microbes, as well as some multicellular organisms. Rogers emphasizes that the team erred strongly on the conservative side while reporting their findings. They chose to include only those genetic sequences that they were absolutely certain came from the accretion ice. Because of this, Rogers believes there are most likely a multitude of other organisms in the lake, opening the door to further research.

Additional resources

- Check out Live Science's Guide to Antarctica (Infographic), which provides a map of notable places such as research stations, significant glaciers, explorations and more.

- Learn more about Antarctica's subglacial lakes from glacial scientist Bethan Davies. The page describes how the lakes are found and even includes an animation of subglacial lake behavior.

- Learn about what would happen if you fell into Lake Vostok, with this "What If" video on YouTube.

Additional reporting by Traci Pedersen, Live Science contributor.

Editor's note: This article was last updated on Dec. 20, 2021.

Originally published on Live Science.