Ancient Primate Skeleton Hints at Monkey and Human Origins

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

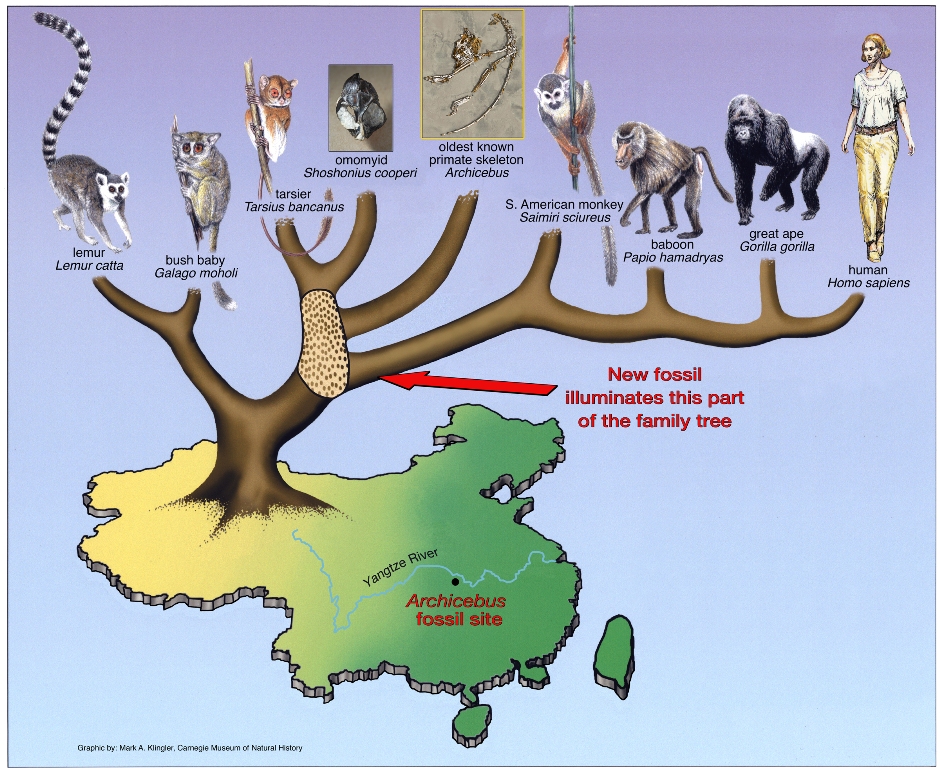

The oldest well-preserved skeleton of a primate, a 55-million-year-old specimen found in China, has been discovered, researchers report.

The primate appears to be the most primitive known relative of the group that contains tarsiers, small primates found only in Southeast Asia. The finding suggests this group diverged from anthropoids, the group that contains monkeys, apes and humans, during the Eocene epoch (55.8 million to 33.9 million years ago), a time of widespread warming.

It's not the oldest primate fossil, researchers say, but it is one of the oldest most-complete skeletons of the group known as tarsiiformes. [In Photos: A Game-Changing Primate Discovery]

"This discovery is really exciting," vertebrate paleontologist Jonathan Bloch of the University of Florida's museum of natural history told LiveScience, "because it shows us the first really [well-articulated] skeleton of one branch of the crown primate tree," (the group including all primates alive today and their common ancestor). Bloch was not involved in the study.

The fossil confirms speculation that the earliest primates probably lived in trees, ate insects and were active during the daytime.

The primate, now named Archicebus achilles (roughly translated as "ancient monkey"), would have weighed about 1 ounce (20-30 grams), suggesting the earliest primates were very small. The skeleton shares some features of tarsiers and some of anthropoids. For instance, the specimen's heel bone strongly resembles those of anthropoids, hence the species name, "achilles."

According to the researchers, this fossil and other evidence suggest the first steps of primate evolution took place in Asia, rather than Africa. But Bloch and others disagree with this interpretation.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Crown primates appeared simultaneously in North America, Europe and Asia 56 million years ago," Bloch said. "I don't think this specimen tells us much about where primates themselves evolved," he added.

The fossil was dug up from an old lake bed in central China's Hubei Province, close to where the Yangtze River now flows.

The fossil was scanned with X-rays at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in Grenoble, France, to produce a 3D digital reconstruction without damaging the specimen.

The Archicebus skeleton is roughly 7 million years older than the previously known oldest fossil primate skeletons, which include Darwinius from Messel, Germany, and Notharctus from the Bridger Basin, Wyoming.

Archicebus is not the oldest primate, anthropologist Mary Silcox of the University of Toronto Scarborough, Canada, told LiveScience. Nevertheless, "this new species will significantly impact our understanding of what is primitive for the common ancestor of living primates," Silcox said.

The findings were reported online today (June 5) in the journal Nature.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus