Most complete Homo habilis skeleton ever found dates to more than 2 million years ago and retains 'Lucy'-like features

Scientists have revealed the most complete skeleton yet of our 2 million-year-old ancestor Homo habilis.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Paleoanthropologists have announced the world's most complete skeleton of Homo habilis, a human ancestor that lived more than 2 million years ago in northern Kenya. The collection of fossil bones has revealed unusually strong arms that distinguished H. habilis from later species.

The bones were initially found in 2012 by a team of researchers led by Meave Leakey, of the Turkana Basin Institute, and were subsequently announced in 2015 at a research conference. Now, the complete analysis of the remains has been described in a paper published Tuesday (Jan. 13) in the journal The Anatomical Record.

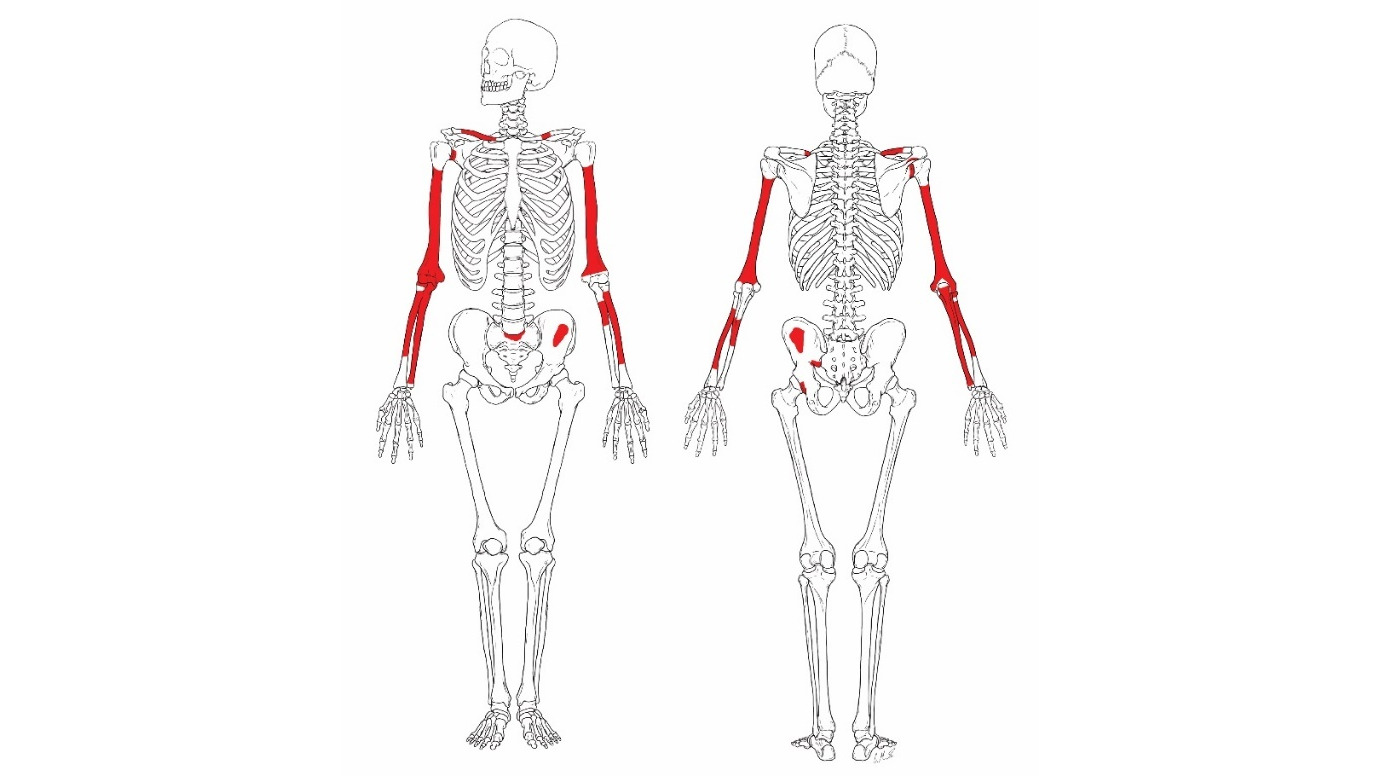

The skeleton, designated KNM-ER 64061, was found in geological layers dated to between 2.02 million and 2.06 million years ago. A complete set of lower teeth clearly identified the skeleton as H. habilis. The skeleton included the collarbones; pieces of the shoulder blades; all of the upper and lower arm bones; and fragments of a vertebra, a rib, an upper leg bone, and the pelvis, making it the most complete H. habilis skeleton ever recovered, as well as one of the oldest, the researchers noted in the study. (The oldest H. habilis skeleton on record is from Ethiopia and dates to 2.33 million years ago.)

Article continues below"There are only three other very fragmentary and incomplete partial skeletons known for this important species," study lead author Fred Grine, a paleoanthropologist at Stony Brook University in New York, said in a statement. The find is significant because it represents both the most complete and the oldest partial skeleton of early Homo, the researchers wrote in the study.

H. habilis was a transitional species, in that it's the first named species to kick-start our genus after evolving from australopithecines — the lineage that includes the celebrity fossil skeleton "Lucy" — but was distinct from our much better understood ancestor Homo erectus, which spread around the world. Fossils from H. habilis are therefore key to understanding the adaptations of our early hominin ancestors. Hominins include modern humans and our extinct relatives.

A close analysis of the KNM-ER 64061 fossils revealed that the arm bones of H. habilis were similar to those of other early Homo specimens and to those of some australopithecines. For example, H. habilis had a longer forearm than did the later H. erectus and had heavy, thick arm bones more similar to those of australopithecines.

Based on the length of the humerus (the upper arm bone), the researchers determined that KNM-ER 64061 was a young adult who was about 5 feet, 3 inches (160 centimeters) tall. From the leg bone fragment, they estimated that the individual weighed only about 67.7 pounds (30.7 kilograms). These anatomical traits suggest that H. habilis retained upper-limb proportions similar to australopithecines' and was shorter and weighed less than H. erectus.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But those traits don't necessarily mean H. habilis could swing through the trees, according to the researchers. "The relatively long forearm of H. habilis may have enabled a greater degree of arboreal locomotion in this species than in H. erectus, but whether arboreality was indeed practiced by H. habilis must remain a matter of speculation," they wrote in the study.

"Homo habilis limbs have been coming more and more into focus," study co-author Ashley Hammond, a paleoanthropologist at the Catalan Institute of Paleontology Miquel Crusafont, said in the statement, and the new skeleton "confirms that the arms were fairly long and strong. What remains elusive is the lower limb build and proportions."

Only a few fragments of KNM-ER 64061's pelvis were recovered, but they suggest that this H. habilis individual may have walked more like H. erectus than like earlier australopithecines, the researchers noted in the study.

"Going forward, we need lower limb fossils of Homo habilis, which may further change our perspective on this key species," Hammond said in the statement.

The discovery of a surprisingly complete H. habilis skeleton may also help paleoanthropologists sort out the abundance of hominin groups that lived in eastern Africa between 2.2 million and 1.8 million years ago.

Researchers have found that up to four hominin species — Paranthropus boisei, H. habilis, Homo rudolfensis and probably H. erectus — lived in the same place around the same time. And because H. erectus appeared nearly 500,000 years before H. habilis disappeared from the fossil record, it is currently unclear whether H. habilis was the ancestor to H. erectus or a related species.

Human evolution quiz: What do you know about Homo sapiens?

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Kristina holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology and an M.A. in classical archaeology from the University of North Carolina, as well as a B.A. in Latin from the University of Virginia, and she was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus