Left vs. Right: Can We Ever Get Along?

First there were the debates. The partisan attacks. Your normally mild-mannered friends cluttering up your Facebook newsfeed with political rants.

And now, the election is over.

The next question is, will our politicians be able to come together to govern the country over the next four years? And will you and Aunt Mildred be able to civilly pass the peas over Thanksgiving dinner after that knock-down, drag-out fight you had about health-care reform on Election Day?

Political psychologists say yes, but only if liberals and conservatives alike step outside their own opinions to try to understand why the other side believes as it does. That's difficult, research has shown, because the right and the left base their views on very different morals — and emotions often run hotter than logic.

"When you have a big contest and one person loses, it doesn't necessarily mean that everyone's going to run to the middle or that one side will admit that they're wrong," said Peter Ditto, a psychologist who studies moral decision-making at the University of California, Irvine. [The History of Human Aggression]

Voting values

Research pioneered by New York University psychologist Jonathan Haidt has found that people tend to arrange their values along six different areas, or domains. The first, care versus harm, concerns people's empathy and desire not to see others hurt. The second, fairness versus cheating, is concerned with justice and rights. Liberals tend to see fairness as an issue of equality, while conservatives see it as an issue of proportionality. That helps to explain liberals' desires to see a large social safety net versus the conservative attitude that people should get what they work for and no more.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Liberals derive their values largely from the first moral domain, though they also care about the second. Liberals also worry about the third domain, liberty and oppression, which motivates people to stand up against bullies and fight for individual liberties.

Conservatives care about these values, too. But they also care about three other moral domains that liberals tend to shrug off. These include: loyalty and betrayal, which concerns patriotism and group identity; authority versus subversion, which includes deference to social hierarchies; and sanctity versus degradation, which concerns disgust and beliefs about the desecration of the body.

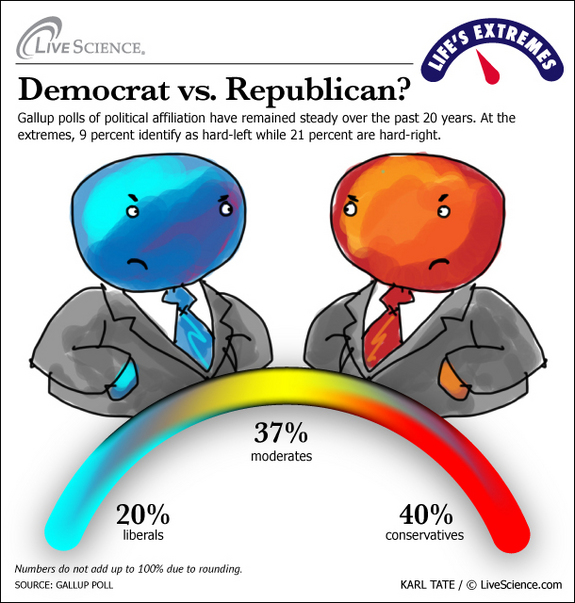

With these very basic concerns driving people's political beliefs, it's easy to see how the political left and right see issues very differently. A conservative, for example, might be disgusted by gay marriage, believing that homosexuality desecrates the body. A liberal, on the other hand, wouldn't worry about the sanctity versus degradation domain; his or her concerns would involve causing the least harm to gay couples, falling under the domain of harm versus care. [Life's Extremes: Democrat vs. Republican]

As politics has come to encompass more and more issues of daily life, fights over these values feel personal and emotional, said Matt Motyl, a doctoral student in social psychology at the University of Virginia who researches political incivility.

"There is just so much that is now encompassed by politics," Motyl told LiveScience. "It's not just voting about one party or the other, it's about right and wrong, good and evil, black and white."

Coming together

Understanding these differences and their emotional weight doesn't mean liberals and conservatives will automatically see eye-to-eye, of course. But researchers say that there are ways to keep political discourse civil and cooperative, at least.

First step: Get out of your bubble.

"Over the past few decades, liberals and conservatives have been migrating into moral enclaves," Motyl said. "They rarely communicate or have close relationships with people with different moral values."

Similarly, polarized media provides a ready-made place for people to hear their worldview reinforced, Ditto told LiveScience.

"These places make money when people fight, and they're not going to make money when people cooperate," Ditto said. He suggested "breaking out of the media cocoon" to listen to how the other side frames issues.

When it comes time to actually talk face-to-face with someone on the other side of the political spectrum (Thanksgiving dinner, anyone?), Ditto recommends asking questions rather than arguing. Arguing, he said, tends to entrench people in their own positions. We convince ourselves that our beliefs are based on logic, when in fact, Ditto said, a great deal of our moral decisions are emotional.

Instead of arguing, asking people why they believe what they believe can be more productive, Ditto said.

"If you ask people why do they think what they think, you'll very often find that what they say isn't very different from what you think," he said. "It's framed in a different way or wrapped up in all of the political garbage and conflict that's there, but underneath that there's more commonality than people think."

Of course, you can always just avoid the topic of politics at your next holiday meal. But despite conventional wisdom, family political debates aren't always a bad thing, Motyl said. In fact, they may be our best hope at seeing the other side as real human beings instead of caricatures.

"If we can have these conversations, this is probably the best place we can try to have them because our families presumably love us and they're stuck with us for better or worse," he said. "And because we know them, we can't just assume this person is evil and stupid."

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas or LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus