What are stingrays?

Graceful sea-pancakes with a dangerous tail.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

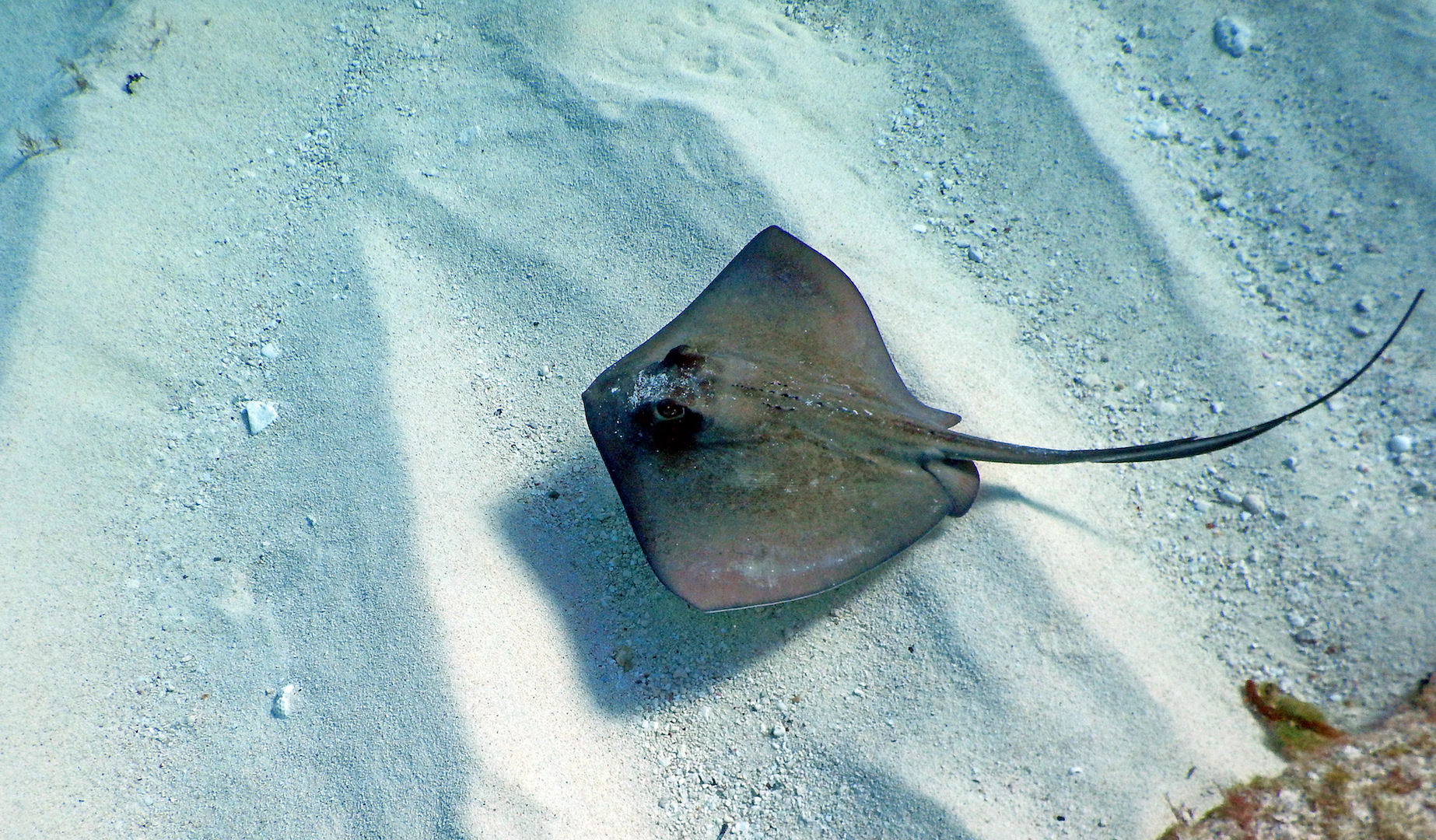

Stingrays are an instantly recognizable fish, with their pancake-like bodies that glide gracefully through the water. Around 200 species of stingrays inhabit the world's oceans, as well as some freshwater rivers and lakes. Stingrays around the world face threats to their continued survival.

What are stingrays?

Like sharks, stingrays belong to a class of animals called elasmobranchs, which are characterized by their boneless skeletons made of cartilage — the same semi-flexible protein that gives shape to human ears. The stingray's flat body allows it to sit on the bottom of the ocean, river or lake, camouflaging itself to predators swimming above as it hunts its prey on the floor. Its eyes sit on the top of its body, while its mouth is on the bottom. Stingrays have tails which often have a serrated, toxin-filled barb. If a stingray feels threatened, it can lift its barbed tail upward and injure potential predators.

Related: Stingrays' weird swimming may inspire new submarine design

Most stingrays live in coastal saltwater environments rather than the open ocean, said Stephen Kajiura, professor of biology at Florida Atlantic University. However, there is one species of stingray that lives in open ocean waters, called the pelagic stingray (Pteroplatytrygon violacea), he said.

Stingrays range in size from about as small as a dinner plate to as big as 16.5 feet (5 meters) long including the tail, according to National Geographic. The largest species is the giant freshwater stingray (Himantura chaophraya), found in rivers in southeast Asia. Some specimens of freshwater stingray have been known to weigh up to 1,300 lbs (590 kg).

Related: Giant stingray could be world's largest freshwater fish

Most species of stingrays sport dull colors that help with camouflage, though some do have more lively colors, such as the blue-spotted stingray (Taeniura lymma), Kajiura said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Are stingrays the same as manta rays or eagle rays?

Stingrays, manta rays and eagle rays are all related and belong to the same order, Myliobatiformes, but each are in different families and differ from one another in several ways.

For example, the manta ray's mouth is located on the front of their bodies rather than on the bottom, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Also, manta rays aren't hunters like stingrays, but are filter feeders, swimming with their mouth open to sift out small animals living in the water column, Kajiura said. Manta rays also have two small appendages that stick out on either side of their mouth called cephalic fins, according to NOAA, which stingrays don't have. And while there are over 200 species of stingrays, there are just 2 species of manta rays.

Related: Rare pink manta ray caught courting lady friend down under

Eagle rays, such as the spotted eagle ray (Aetobatus narinari), have angular wing flaps and a distinct snout that manta rays and stingrays don't have, according to the Florida Museum. Eagle rays also have rounded pelvic fins near their tail, and the tail itself is much longer than either a manta ray or stingray. Sometimes, eagle rays travel in schools and will leap completely out of the water to avoid predators, according to the Florida Museum.

What do stingrays eat?

Stingrays eat bottom-dwelling prey, such as worms, clams and shrimp, according to SeaWorld Orlando. Freshwater stingrays eat insects as well.

As those creatures (and any others) move through the water, they generate a bioelectric field, or electrical signature of sorts, said Kyle Newton, a biologist at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri. Stingrays are able to detect the bioelectric fields of the animals around them using a network of special sensory organs called ampullae of Lorenzini. These organs are small, fluid-filled electrical receptors that are located near the stingray's mouth and look like tiny black holes in the animal's skin, according to National Geographic. All sharks and rays have ampullae of Lorenzini, and a few other species of fish have been reported to have the unique organs as well, including lungfish and sturgeon.

Related: Clever cuttlefish 'freeze' bioelectric fields to avoid predators

Once they've located and captured their prey with the help of their ampullae of Lorenzini, stingrays use their hard teeth to break the shells of their victims, and can even chew their meal, rather than gulping it down. Stingrays go through a lot of teeth, shedding a complete set every 10 to 30 days, Kajiura said.

Most of the time, stingrays have rounded, flat molars, but during mating season, the male stingray's teeth become pointed, though not as pointed (or as large) as shark teeth. The stingray "is the only vertebrate we've documented that has seasonal changes in tooth shape," Kajiura said. The male stingray uses its sharper teeth to secure himself to a mate during reproduction, as stingrays are rather slippery. Females are often left with scars from mating. However, in at least one species of stingray, the female's skin is 50% thicker than the males, providing her a bit of protection from the male's sharp teeth, Kajiura said.

Related: This stingray chews its food

When do stingrays mate?

Mating season lasts a few months (which months depends on the species of stingray), and teeth that grow afterward resume the regular flat shape in males.

Female stingrays often have long gestation periods, ranging from 6 months to 2 years, Newton said. They tend to give birth once a year to between two and six live young, according to National Geographic Kids.

Newborn stingrays "come out as fully functional miniatures of the adult," Newton said. Baby stingrays are often small enough to fit in a human palm, and sometimes look "squatty" and "pudgy," he said.

How long stingrays live varies greatly by species, Kajiura said. Many live much shorter lives, closer to 6-8 years. Some larger freshwater species, like the giant freshwater stingrays of Southeast Asia, may live 25 years or longer, but scientists don't know for sure, he said. In general, scientists are most familiar with the life cycles of commercially important fish, but because stingrays aren't heavily fished, the lifespan of many species remains unknown, he said.

Are stingrays dangerous?

In 2006, Australian television personality Steve Irwin died when a stingray's barbed tail pierced his heart. Irwin, widely known for his popular show, "The Crocodile Hunter," was being filmed for another show, called "Ocean's Deadliest," when he swam too close to a stingray.

Related: Stingray kills 'Crocodile Hunter' Steve Irwin

However, death from stingrays is rare, according to the US National Library of Medicine. A stingray's poison is generally only deadly when its barb pierces a vulnerable part of the body, as it did for Irwin. These areas include the neck, abdomen or chest. Otherwise, contact with a stingray's barb anywhere else on the body causes pain similar to a jellyfish sting, and thousands of people the world over survive stingray stings each year, according to NPR.

Stingrays can detect magnetic fields

In addition to being able to sense the bioelectric fields of the animals around them, scientists believe that stingrays and other elasmobranchs have the ability to sense the polarity of the Earth's magnetic field, Newton said. This ability is called magnetoreception.

Salmon may be most famous for this. The migratory fish have crystals of iron or other magnetic metals embedded in their cells, which scientists think help them navigate to the streams they were born in to spawn, Kajiura said. But researchers have yet to find similar crystal structures in stingrays and other elasmobranchs.

Some scientists suspect that stingrays may use their ampullae of Lorenzini not only for hunting prey, but also for detecting the strength and angle of the Earth's magnetic field and the orientation of electric currents generated by objects in the water. The stingray could then use that information to navigate in the open ocean, similar to other animals with magnetoreception abilities.

In their study published in 2020 in the journal Marine Biology, Newton and Kajiura described how wild-caught yellow stingrays (Urobatis jamaicensis) used magnetoreception to navigate through a simple maze to receive a food reward. Other elasmobranchs may similarly detect magnetic fields, the researchers said.

Related: What if Earth's magnetic field disappeared?

The stingray's magnetoreception abilities could potentially cause problems for the animals as offshore energy technologies like wind and wave energy become more popular, Kajiura said. That's because those technologies require a network of cables to transport electricity from where it is generated to where people live onshore, and the electric current generated by those cables could interfere with the stingray's ability to accurately detect their surroundings. This could disrupt the stingray's feeding and migration patterns or cause stingrays to avoid certain areas altogether, Newton said. Alternatives like burying the cables in the seafloor would likely be prohibitively costly. But it's still unclear how each species of stingray in a given area would be affected by the presence of cables, he said.

Are stingrays endangered?

While the long-term effects of offshore technologies on stingrays has yet to be seen, the fish already face a variety of other threats to their survival. A study published by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) in 2014 found that one quarter of the planet's stingrays and sharks are at risk of extinction, with more stingrays facing extinction than sharks.

The main risk comes from overfishing, according to the study. Stingrays aren't often targeted commercially, but get caught as bycatch by fishers who use large trawling nets to fish the ocean from the surface to the seafloor.

Related: What if there were no sharks?

Some species of stingrays also face overharvesting for the aquarium trade, Newton said. While some fish species are easy to raise in captivity, stingrays' long gestation period means it's preferable for many sellers to harvest them straight from the ocean to sell, Newton said.

Freshwater stingrays might be vulnerable to pollution from humans, while marine species like the yellow stingray are also suffering habitat loss from coastal development, according to research by the Save Our Seas Foundation.

In Florida, some species of stingrays prefer using mangrove forests — coastal trees whose roots are submerged in seawater — as birthing grounds because of the protection offered to young from the trees and their roots, Newton said. But Florida has lost much of its original mangrove habitat, rendering young without sufficient shelter and leaving them vulnerable to predation.

Additional resources:

- Watch stingrays sense electricity in this video from PBS Digital Studios Deep Look.

- Read more about the yellow stingray, from the Florida Museum.

- Learn more about the freshwater stingray, from the Smithsonian National Zoo.

Erin Banks Rusby is a journalist based in Boise, Idaho. Erin has a Bachelor's degree in Biology and Spanish from Williamette University and a Master's degree in Journalism from the University of California, Berkeley. Erin became a journalist to bring my two main passions — ecology and writing — together, and she has reported stories on ecology and other topics, including COVID-19 policy in Idaho, for the Idaho Press, Mongabay, Live Science and other outlets. When she's not writing, you'll find her biking Boise's Greenbelt and snuggling her dog, Pickles.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus