How Bad Can the NYC Measles Outbreak Get?

A growing measles outbreak in New York City has led officials to declare a public health emergency in parts of the city.

There have been nearly 300 confirmed measles cases in the city since the outbreak began last October, mainly in Orthodox Jewish communities in parts of Brooklyn, according to the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH). What's more, another outbreak is ongoing in the New York county of Rockland, which is north of New York City.

But how much worse could the outbreak get, and how far could it spread?

Experts told Live Science that the outbreak could keep growing for sometime, although cases would likely be restricted to certain areas.

"I would expect that this outbreak is going to get bigger before it comes under control," said Dr. Amesh Adalja, a senior scholar at The Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security in Baltimore. [27 Devastating Infectious Diseases]

The U.S. as a whole has fairly high vaccination rates against measles, and the vaccine is very effective at preventing the disease. But "there are pockets that have lower than required [vaccination rates] to keep measles at bay," Adalja told Live Science. It's in these areas where there's potential for a lot of measles spread.

Dr. Robert Glatter, an emergency-medicine physician at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City, agreed that the outbreak "has the potential to escalate" if vaccination coverage isn't adequate in certain areas.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Measles is one of the most contagious infectious diseases out there, so if someone is unvaccinated, the "virus is likely to find them," Adalja said.

Adalja also noted that there are babies being born all the time, who usually can't be vaccinated until they are about 1 year old. "There's always going to be fresh victims for this virus to find," he said. (Health officials in NYC are recommending that babies as young as 6 months in affected areas get the measles vaccine, Buzzfeed News reported.)

And if infected individuals travel to other areas that also have low vaccination rates, they could "seed" outbreaks in those areas, too.

Still, high vaccination rates in other areas serve as a kind of "wall" to prevent the virus from spreading to those areas, Adalja said. But since there's always a small percentage of the population that can't be vaccinated (including young infants), "the wall is never going to be complete," he said.

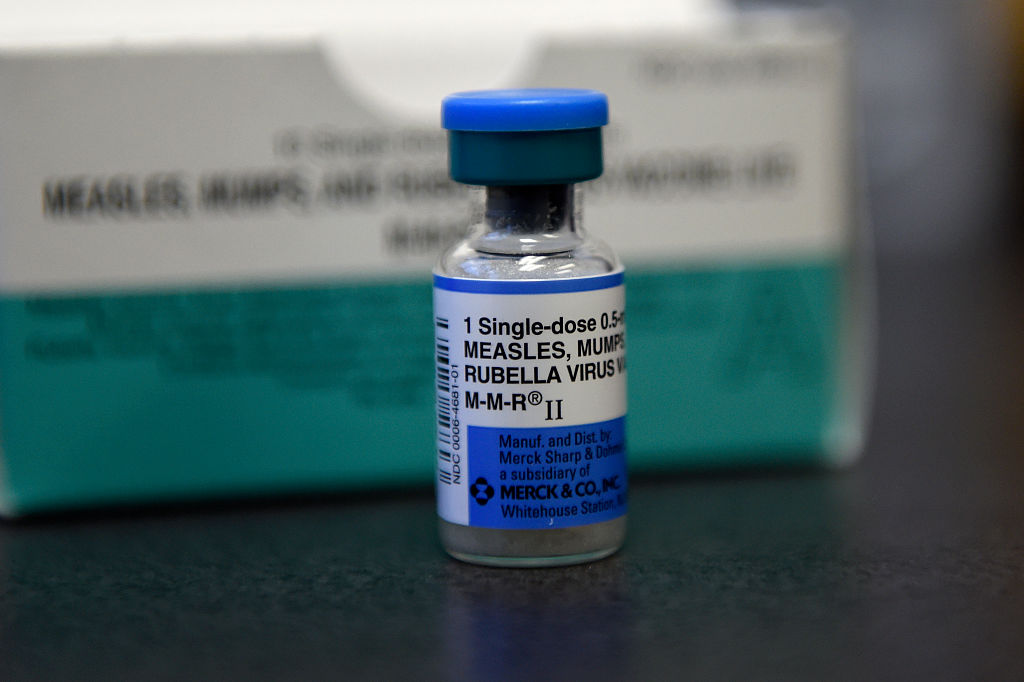

The key to preventing measles outbreaks is adequate vaccination rates. "Vaccines are critical because they can reduce the frequency of outbreaks of disease and therefore can save lives," Glatter told Live Science.

And "because measles is so transmissible, in order to prevent this kind of spread, you have to have very high levels of vaccine [coverage] — well over 90%," said Dr. William Schaffner, an infectious disease and preventive medicine specialist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee.

Yesterday (April 9), New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio announced that unvaccinated people living in certain ZIP codes in Brooklyn will be required to be vaccinated if they may have been exposed to measles. Under the mandatory vaccination order, officials will check the vaccination records of anyone who may have been in contact with a person infected with measles, according to a statement from the DOHMH. People who haven't received the measles vaccine or don't have evidence of immunity could be fined up to $1,000.

This follows an order in Rockland County that barred unvaccinated children from public spaces for 30 days. (However, a New York judge recently ruled against the order.)

These efforts not only aim to stop the outbreak, but also to protect unvaccinated kids from getting sick themselves, Schaffner told Live Science. "We need to remember the second [reason] as well as the first," he added.

As of Monday (April 8), there have been 285 cases of measles in Brooklyn and Queens since October, DOHMH said. Most of these cases (more than 85%) have been in children under age 18. No deaths have occurred, but 21 people have been hospitalized, including five who required admission to the intensive-care unit.

Although measles is sometimes seen as a relatively benign illness, that's not the case, Adalja said. The disease can cause serious complications: About 1 in 4 people who get measles need to be hospitalized, 1 in 20 get pneumonia, 1 in 1,000 develop brain swelling that may lead to brain damage, and about 1 or 2 people out of 1,000 die from the illness, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- 5 Dangerous Vaccination Myths

- 10 Bizarre Diseases You Can Get Outdoors

- 5 Deadly Diseases Emerging from Global Warming

Originally published on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.