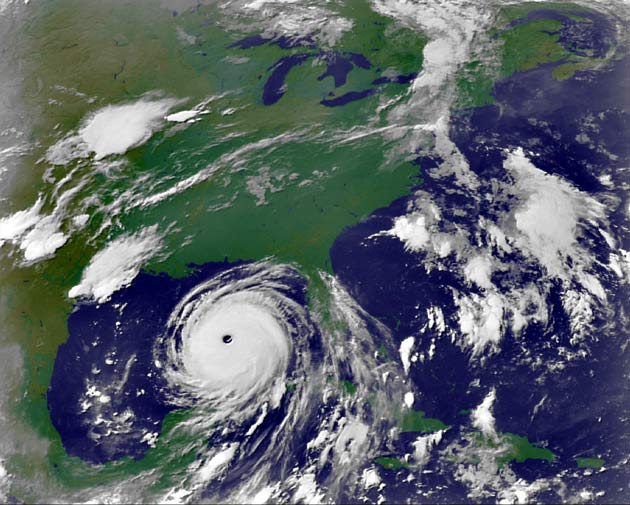

A rise in the world's sea surface temperatures was the primary contributor to the formation of stronger hurricanes since 1970, a new study reports.

While the question of what role, if any, humans have had in all this is still a matter of intense debate, most scientists agree that stronger storms are likely to be the norm in future hurricane seasons.

The study is detailed in the March 17 issue of the journal Science.

An alarming trend

In the 1970s, the average number of intense Category 4 and 5 hurricanes occurring globally was about 10 per year. Since 1990, that number has nearly doubled, averaging about 18 a year.

Category 4 hurricanes have sustained winds from 131 to 155 mph. Category 5 systems, such as Hurricane Katrina at its peak, feature winds of 156 mph or more. Wilma last year set a record as the most intense hurricane on record with winds of 175 mph.

While some scientists believe this trend is just part of natural ocean and atmospheric cycles, others argue that rising sea surface temperatures as a side effect of global warming is the primary culprit.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

According to this scenario, warming temperatures heat up the surface of the oceans, increasing evaporation and putting more water vapor into the atmosphere. This in turn provides added fuel for storms as they travel over open oceans.

Other factors less important

The researchers used statistical models and techniques from a field of mathematics called information theory to determine factors contributing to hurricane strength from 1970 to 2004 in six of the world's ocean basins, including the North Atlantic, Pacific and Indian oceans.

They looked at four factors that are known to affect hurricane intensity:

- Humidity in the troposphere—the part of the atmosphere stretching from surface of the Earth to about 6 miles up

- Wind shear that can throttle storm formation

- Rising sea-surface temperatures

- Large-scale air circulation patterns known as "zonal stretching deformations"

Of these factors, only rising sea surface temperatures was found to influence hurricane intensity in a statistically significant way over a long-term basis. The other factors affected hurricane activity on short time scales only.

"We found no long-term trend in things like wind shear," said study team member Judith Curry of the Georgia Institute of Technology. "There's a lot of year to year variability but there's no global trend. In any given year, it's different for each ocean."

An answer for the critics

The new study potentially addresses one major criticism leveled by scientists skeptical of any strong link between sea surface temperatures and hurricane strength, said Kerry Emanuel, a climatologist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who was not involved in the study.

Last year, Emanuel published a study correlating the documented increase in hurricane duration and intensity in the Atlantic and Pacific oceans since the 1970s to rises in sea surface temperatures over the same time period.

"We were criticized by the seasonal forecasters for not including the other environmental factors, like wind shear, in our analysis," Emanuel said in an email. "[We didn't do so] because on time scales longer than 2-3 years, these do not seem to matter very much. This paper more or less proves this point."

Kevin Trenberth, the head of climate analysis at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR), believes the new study's main finding is accurate but thinks the effects of some of the environmental factors on hurricane intensity might have been underestimated.

"The reason is they're covering a period from 1970 to 2004. 1979 is the year when satellites were introduced into the [NCEP/NCAR] Reanalysis. The quality of the analysis prior to 1979 is simply nowhere near as good," said Trenberth, who also was not involved in the study.

The NCEP/NCAR Reanalysis is the database the researchers drew upon for information about the effects of troposphere humidity, wind shear and zonal stretching deformation on hurricane intensity; sea surface temperature data came from a different database.

Curry acknowledged that reanalysis data prior to 1979 is of slightly lower quality than more recent data but believes this doesn't substantially change the study's main finding. Trenberth agreed: "I suspect they may well have gotten the right answer anyway," he told LiveScience.

Natural cycles?

Some scientists have explained the rising strength of hurricanes as being part of natural weather cycles in the world's oceans.

In the North Atlantic, this cycle is called the Atlantic multi-decadal mode. Every 20 to 40 years, Atlantic Ocean and atmospheric conditions conspire to produce just the right conditions to cause increased storm and hurricane activity.

The Atlantic Ocean is currently going through an active period of hurricane activity that began in 1995 and which has continued to the present. The previous active cycle lasted from the late 1920's to 1970, and peaked around 1950.

These cycles definitely do influence hurricane intensity, but they can't be the whole story, Curry said.

While scientists expect stronger hurricanes based on natural cycles alone, the researchers suspect other contributing factors, since current hurricanes are even stronger than natural cycles predict.

"We're not even at the peak of current cycle, we're only halfway up and already we're seeing activity in the North Atlantic that's 50 percent worse than what we saw during the last peak in 1950," Curry said.

Some scientists still think it's too premature to make any definitive links between sea surface temperatures and hurricane intensity.

"We simply don't have enough data yet," said Thomas Huntington in of the U.S. Geological Survey. "Category 5 hurricanes don't come around very often, so you need the benefit of a much longer time series to look back and say 'Yup, there has been an increase.'"

Huntington is the author of a recent review of more than 100 peer-reviewed studies showing that although many aspects of the global water cycle—including precipitation, evaporation and sea surface temperatures—have increased or risen, the trend cannot be consistently correlated with increases in the frequency or intensity of storms or floods over the past century. Huntington's study was announced this week and is published in the current issue of the Journal of Hydrology.

Brace yourselves

Whatever the underlying cause, most scientists agree that people will need to brace themselves for stronger hurricanes and typhoons in the coming years and decades.

However, most regions around the world will not experience more storms. The only exception to this is the North Atlantic, where hurricanes have become both more numerous and longer-lasting in recent years, especially since 1995. The reasons for this regional disparity are still unclear.

The team's findings are controversial because they draw a connection between stronger hurricanes and rising sea surface temperatures—a phenomenon that has itself already been linked to human-induced global warming.

The study by Curry and her colleagues therefore raises the frightening possibility that humans have inadvertently boosted the destructive power of one of Nature's most devastating and feared storms.

"If humans are increasing sea surface temperatures and if you buy this link between increases rising sea surface temperatures and increases in hurricane intensity, that's the conclusion you come to," Curry said.

- 2006 Hurricane Guide

- Global Warming May Play Role in Hurricane Intensity

- Study: Global Warming Making Hurricanes Stronger

- Increase in Major Hurricanes Linked to Warmer Seas

- How & Where Hurricanes Form

- Many More Hurricanes to Come

Image Gallery

Hurricanes from Above

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus