Earth's energy imbalance is rising much faster than scientists expected — and now researchers worry they might lose the means to figure out why

For reasons still unknown, Earth's energy imbalance is rising much faster than models can account for. Now, scientists are calling for long-term investment in monitoring capability, so that they can make informed predictions about climate change.

Earth's energy imbalance is growing faster than anyone expected — and scientists don't understand why.

To complicate matters several NASA satellites that provide the highest-resolution picture of this imbalance are nearing the end of their lives, and researchers fear their lone replacement isn't sufficient. In the worst case scenario, scientists could lose one of the leading indicators of climate change, as the next-best way of measuring the energy imbalance has a lag of about 10 years.

"What we get from [these] satellites is roughly one decade faster data, so that's why it's so critical," Thorsten Mauritsen, a professor in the department of meteorology at Stockholm University in Sweden and the lead author of a commentary on the issue, told Live Science. "The absolute best option is that NASA continues."

Earth's energy imbalance is the difference between the amount of energy our planet receives from the sun and the amount it radiates outward into space. The imbalance is mainly caused by our emissions of greenhouse gases, which trap a portion of the energy radiating from Earth inside the atmosphere, driving temperatures up.

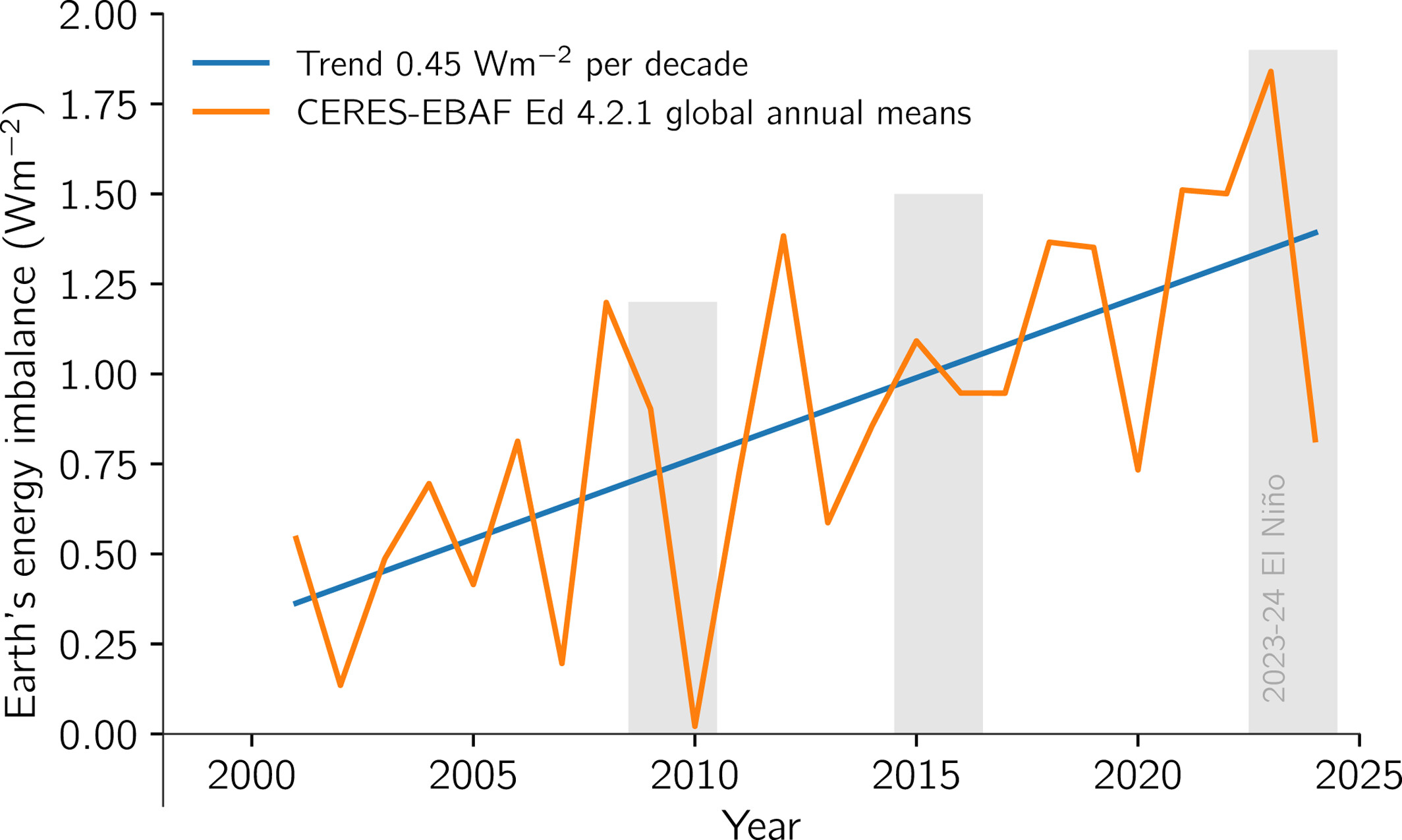

Satellite data suggest Earth's energy imbalance has more than doubled over the past two decades, massively exceeding the increase predicted by climate models. In 2023, the imbalance reached 1.8 watts per square meter (0.16 watts per square foot), which was twice what models estimated based on rising greenhouse gas emissions, according to the commentary, which was published May 10 in the journal AGU Advances — but scientists still aren't sure why there has been such an increase in the imbalance recently.

"We were starting to see this large trend in the last few years, and it just grew and grew," Mauritsen said. "We were both worried about the big trend, and then on the other hand that we are possibly about to lose capability to observe this."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For several years, researchers have puzzled over satellite readings of Earth's energy imbalance. At first, it seemed like the numbers might be reflecting the variability of the system and changes due to climate patterns such as El Niño, Mauritsen said.

But as the imbalance continued to grow faster than climate models could account for, scientists began to suspect that something bigger was happening. "When it just continued afterwards, I started to get worried," Mauritsen said.

Earth's inflated energy imbalance is likely due to a decline in Earth's solar reflectivity — that is, in the amount of energy the planet radiates to space. This decline could be due to a number of reasons, Mauritsen said, including a reduction of reflective surfaces like ice sheets and a decrease in the quantity of reflective particles, or aerosols, from activities like shipping. But the actual reasons remain mysterious.

"Something is missing [from the models], but we don't really know right now what it is," Mauritsen said.

Regardless of why Earth's energy imbalance is growing so rapidly, the implications are alarming. "The larger the imbalance is, the faster climate change happens," Mauritsen said. "If we have more imbalance, that means more energy accumulating, [so] temperatures rise faster."

Earth's energy imbalance is also an important indicator of how far humans have pushed the climate system already, and of what it will take to balance it again.

"We expect temperatures to stabilize after we stop burning fossil fuels, roughly," Mauritsen said. "But if that imbalance stays very high, then it pushes further that temperature level that we can stabilize at. That means we have less CO2 left that we can emit before we get to 2 degrees Celsius [or 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit of warming], for example."

Satellite readings from 2024 indicate that the rate at which Earth's energy imbalance is growing has returned to levels predicted by climate models — but there's no telling what will happen in 2025 and beyond. "It may be in the coming years that we stay at these more expected levels," Mauritsen said. "If it does bounce up to those high levels [again], then I'm not sure where we're heading."

Scientists need satellites

To measure Earth's energy imbalance, scientists need satellites equipped with the right instruments. Four such satellites are currently operational and form part of NASA's CERES mission, and these are scheduled to be replaced in 2027 by the follow-on Libera mission, according to the new commentary.

But Libera has only one satellite, and scientists worry that instrument failures could introduce gaps in the data, Mauritsen said — and without continuous and overlapping readings from different satellites, it will be much harder to piece together the evolution of Earth's energy imbalance.

NASA also has no formal plan to continue monitoring the imbalance once the Libera mission ends, and other instruments aboard the International Space Station have limited mission lifetimes, according to the commentary.

Ocean temperature data give some indication of Earth's energy imbalance, but these records only reveal trends a decade after they have happened, and give a much less spatially-refined picture of the imbalance, Mauritsen said.

The agency is brimming with ideas that could advance climate science, but new budget cuts by the Trump administration may put a wrench in the works. For example, NASA scientists recently came up with a "really cool" idea to measure Earth's energy imbalance with spherical satellites, Mauritsen said. These satellites would carry accelerometers capable of measuring radiation from all angles, and then integrating the different sources to calculate the energy imbalance.

In the new commentary, Mauritsen and dozens of researchers from institutions across the world call for improved monitoring capability and more research into the evolution of Earth's energy imbalance.

"It tells us how far we are from stabilizing Earth's climate, and that's why we need to measure it," Mauritsen said. "If we don't know this, then we are driving our climate system blindfolded."

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus