'It's a ticking time bomb': Acid levels in Earth's oceans have already breached 'danger zone', study suggests

Researchers have found that ocean acidification entered a "danger zone" in 2020, suggesting increased carbon dioxide levels have caused Earth to breach another planetary boundary.

Earth's oceans are in worse condition than scientists thought, with acidity levels so high that our seas may have entered a "danger zone" five years ago, according to a new study.

Humans are inadvertently making the oceans more acidic by releasing carbon dioxide (CO2) through industrial activities such as the burning of fossil fuels. This ocean acidification damages marine ecosystems and threatens human coastal communities that depend on healthy waters for their livelihoods.

Previous research suggested that Earth's oceans were approaching a planetary boundary, or "danger zone," for ocean acidification. Now, in a new study published Monday (June 9) in the journal Global Change Biology, researchers have found that the acidification is even more advanced than previously thought and that our oceans may have entered the danger zone in 2020.

The researchers concluded that by 2020, the average condition of our global oceans was in an uncertainty range of the ocean acidification boundary, so the safety limit may have already been breached. Conditions also appear to be worsening faster in deeper waters than at the surface, according to the study.

"Ocean acidification isn't just an environmental crisis — it's a ticking time bomb for marine ecosystems and coastal economies," Steve Widdicombe, director of science and deputy chief executive at Plymouth Marine Laboratory, a marine research organization involved in the new study, said in a statement. "As our seas increase in acidity, we're witnessing the loss of critical habitats that countless marine species depend on and this, in turn, has major societal and economic implications."

Related: Atlantic ocean currents are weakening — and it could make the climate in some regions unrecognizable

In 2009, researchers proposed nine planetary boundaries that we must avoid breaching to keep Earth healthy. These boundaries set limits for large-scale processes that affect the stability and resilience of our planet. For example, there are boundaries for dangerous levels of climate change, chemical pollution and ocean acidification, among others.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A 2023 study found that we had crossed six of the nine boundaries. The authors of that study didn't think the ocean acidification boundary had been breached at the time, but they noted it was at the margin of its boundary and worsening.

Katherine Richardson, a professor at the Globe Institute at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark who led the 2023 study and was not involved in the new study, told Live Science that she was "not at all surprised" by the new findings.

"We said it was on the edge in our last assessment and, as atmospheric CO2 concentrations have risen since then, it is hardly surprising that it should be transgressed now," Richardson said in an email.

What causes ocean acidification?

Ocean acidification is mostly caused by the ocean absorbing CO2. The ocean takes up around 30% of CO2 in the atmosphere, so as human activities pump out CO2, they are forcing more of it into the oceans. CO2 dissolves in the ocean, creating carbonic acid and releasing hydrogen ions. Acidity levels are based on the number of hydrogen ions dissolved in water, so as the ocean absorbs more CO2, it becomes more acidic.

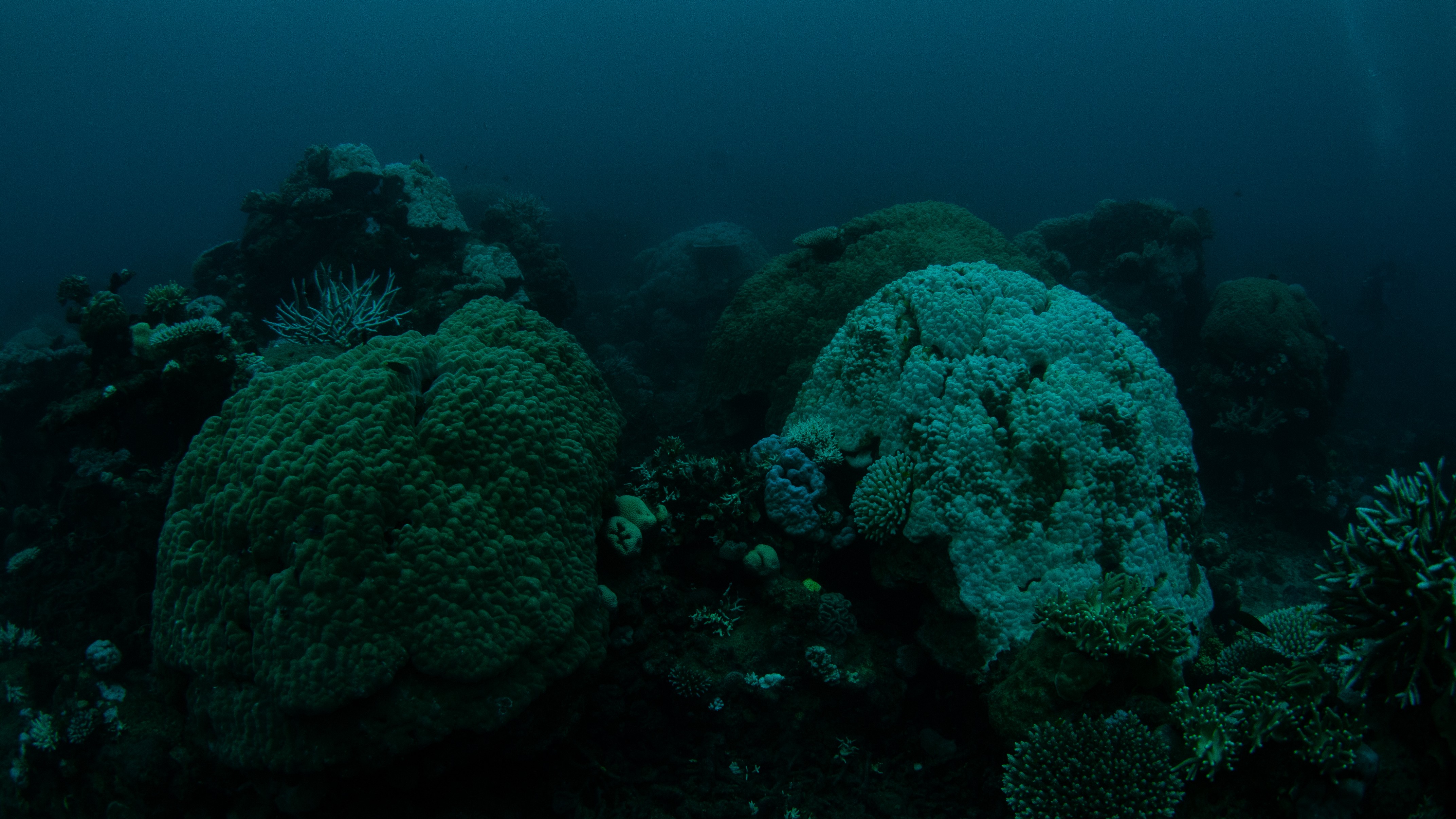

The hydrogen ions bond with carbonate ions in the ocean to form bicarbonate, which reduces the carbonate available to marine life like corals, clams and plankton. These animals need carbonate for their bones, shells and other natural structures, which they make out of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). Researchers measure aragonite — one of the soluble forms of CaCO3 — to track ocean acidity levels.

The ocean acidification boundary would be breached when the oceans see a 20% reduction of aragonite compared with preindustrial levels (estimated ocean acidification for 1750 and 1850). The 2023 study estimated that ocean acidification was at 19%, just below the boundary.

The authors of the new study used physical and chemical measurements in the upper ocean and computer models to update and refine previous ocean acidification estimates. They also introduced a margin of error, including uncertainties in both the boundary and the present-day acidification value.

With the new data, the researchers found that at the ocean's surface, the global average acidification level is 17.3% (with a 5% margin of uncertainty) less than preindustrial levels. That estimate is lower than the 2023 estimate but well within the new study's wider boundary region (20% but with a 5.3% margin of uncertainty). The newly estimated acidification levels increased at greater depths, though the margin for error also increased below 330 feet (100 meters), according to the study's data.

Not all of the ocean is acidifying at the same rate. For example, the researchers determined that about 40% of the water at the surface had crossed the boundary, but that estimate rose to 60% for the waters below, down to about 650 feet (200 m).

"Most ocean life doesn't just live at the surface — the waters below are home to many more different types of plants and animals," study lead author Helen Findlay, a biological oceanographer at the Plymouth Marine Laboratory, said in the statement. "Since these deeper waters are changing so much, the impacts of ocean acidification could be far worse than we thought."

Patrick Pester is the trending news writer at Live Science. His work has appeared on other science websites, such as BBC Science Focus and Scientific American. Patrick retrained as a journalist after spending his early career working in zoos and wildlife conservation. He was awarded the Master's Excellence Scholarship to study at Cardiff University where he completed a master's degree in international journalism. He also has a second master's degree in biodiversity, evolution and conservation in action from Middlesex University London. When he isn't writing news, Patrick investigates the sale of human remains.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus