What is El Niño?

El Niño is a climate cycle in which waters off the tropical eastern Pacific are warmer than usual, which in turn affects global weather patterns.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

El Niño is a climate cycle in the Pacific Ocean which impacts weather patterns around the world.

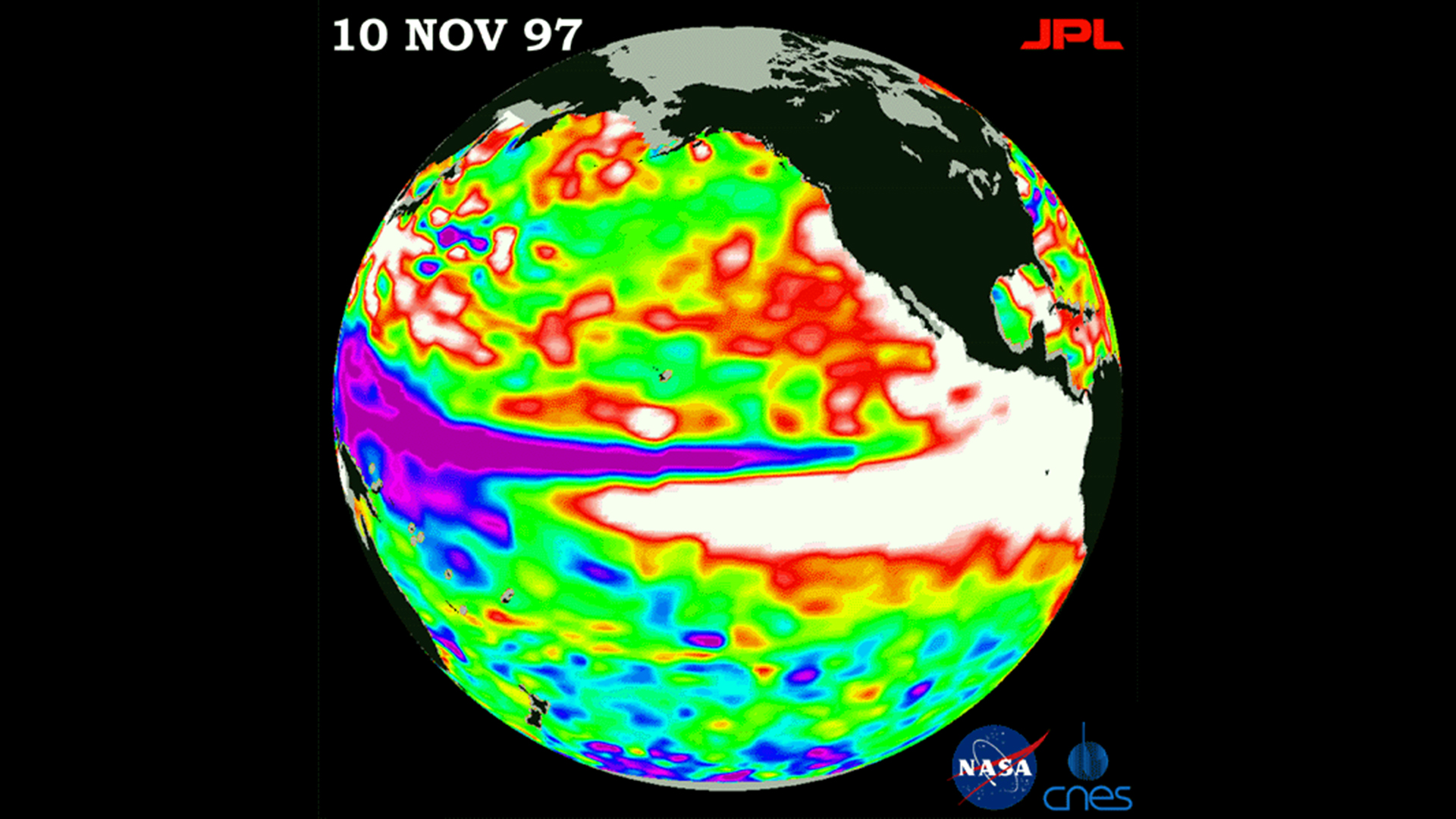

The cycle begins when warm water in the western tropical Pacific Ocean shifts eastward along the equator toward the coast of South America. Normally, this warm water pools near Indonesia and the Philippines. During an El Niño, the Pacific's warmest surface waters sit offshore of northwestern South America.

The location of tropical storms shifts eastward during an El Niño because atmospheric moisture is fuel for thunderstorms, and the greatest amount of evaporation takes place above the ocean's warmest water.

The opposite of El Niño is La Niña, which is when the waters of the tropical eastern Pacific are colder than normal and trade winds blow more strongly than usual.

Collectively, El Niño and La Niña are parts of an oscillation in the ocean-atmosphere system called the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, or ENSO cycle, which also has a neutral phase.

How long will El Niño last?

El Niños occur every three to five years but may come as frequently as every two years or as rarely as every seven years. Typically, El Niños occur more frequently than La Niñas. Each event usually lasts nine to 12 months. They often begin to form in spring, reach peak strength between December and January, and then decay by May of the following year.

Climate scientists at NOAA say there is a more than 95% chance that the current El Niño event will persist into 2024. They expect warmer-than-average conditions that will gradually strengthen into the Northern Hemisphere's fall and winter.

What causes El Niño?

Scientists do not yet understand in detail what triggers an El Niño cycle. Not all El Niños are the same, nor do the atmosphere and ocean always follow the same patterns from one El Niño to another.

To forecast an El Niño, scientists monitor several regions across the Pacific.

"You have to think of each region as an ocean sloshing around," said Neville Sweijd, director of the Alliance for Collaboration on Climate and Earth Systems Science (ACCESS) in South Africa. "Sometimes it sloshes to one side, and sometimes it sloshes to the other. That's El Niño and La Niña."

Experts "monitor the average sea-surface temperature in each region and use that to form a model," he told Live Science. "The models will then predict the likelihood of the manifestation."

In normal, non-El Niño conditions, trade winds blow toward the west across the tropical Pacific, away from South America. These winds pile up warm surface water in the western Pacific so that the sea surface is about 1.5 feet (0.5 meters) higher offshore Indonesia than it is offshore Ecuador. Higher sea-surface temperature causes water levels to expand and rise, and also shifts rainfall from land to ocean.

In a non El Niño year, the sea-surface temperature is also about 14 degrees Fahrenheit (8 degrees Celsius) warmer in the western Pacific. Cooler ocean temperatures dominate offshore northwest South America, due to an upwelling of cold water from deeper levels.

Forecasters declare an official El Niño when they see both ocean temperatures and rainfall from storms veer to the east. Experts who monitor El Niño also look for prevailing trade winds to weaken. These changes set up a feedback loop between the atmosphere and the ocean that boosts El Niño conditions.

What is the El Niño forecast for the 2023-2024 winter?

After months of warning, on June 8, scientists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) confirmed the arrival of the latest El Niño event.

El Niño for the 2023-2024 winter is forecast to be very strong, which means normal sea-surface temperatures in the Pacific Ocean are expected to deviate dramatically from their normal averages. However, their strength does not directly correspond to the severity of their impacts, as this relationship can vary considerably between cycles.

"Their effects vary depending on the intensity, duration, time of year when it develops, and the interaction with other modes of climate variability," said Álvaro Silva, a climate expert at the World Meteorological Organization. "Not all regions of the world are affected, and even within a region, the impacts can be different."

The current El Niño event is expected to push global temperatures into uncharted territory and contribute to global warming crossing the critical 2.7 F (1.5 C) threshold within the next five years. It will most likely intensify extreme weather events associated with climate change — such as heat waves, drought and heavy rainfall — in certain areas.

"El Niño is a strong contributing factor to some of the extremes we have experienced in the past and that we are likely to experience in the next months," Silva told Live Science. "It is very likely that this year or next year we will see the warmest year on record."

Does El Niño cause more rain, or drought?

During an El Niño, the trade winds weaken in the central and western Pacific. Surface water off South America warms up because there is less upwelling of the cold water from below to cool the surface. The clouds and rainstorms associated with warm ocean waters also shift eastward. The warm waters release so much energy into the atmosphere that weather changes all over the planet.

An El Niño creates stronger wind shear and more stable air over the Atlantic, which makes it harder for hurricanes to form there. However, the warmer-than-average ocean temperatures boost eastern Pacific hurricanes, contributing to more active tropical storm seasons.

Strong El Niños are also associated with above-average precipitation in the southern United States. The cloudier weather typically causes below-average winter temperatures in that part of the country, while temperatures tilt warmer than average in the northern U.S. Rainfall is often below average in the Ohio and Tennessee valleys and the Pacific Northwest during an El Niño, according to NOAA.

Record rainfall often strikes Peru, Chile and Ecuador during an El Niño year. Fish catches offshore South America are typically lower than normal because the marine life migrates to the north and south, following colder water.

El Niño also affects precipitation in other areas, including Indonesia and northeastern South America, which tend toward drier-than-normal conditions. Temperatures in Australia and Southeast Asia run hotter than average. El Niño-caused drought can be widespread, affecting southern Africa, India, Southeast Asia, Australia, the Pacific Islands and the Canadian prairies.

Unlike El Niño, La Niña events are characterized by a sustained cooling effect around the equator and eastern tropical Pacific. This often results in stronger and more frequent hurricanes across North America and can lead to heavy flooding in many Pacific Island nations, as well as droughts along the west coast of South America.

What were past El Niño years like?

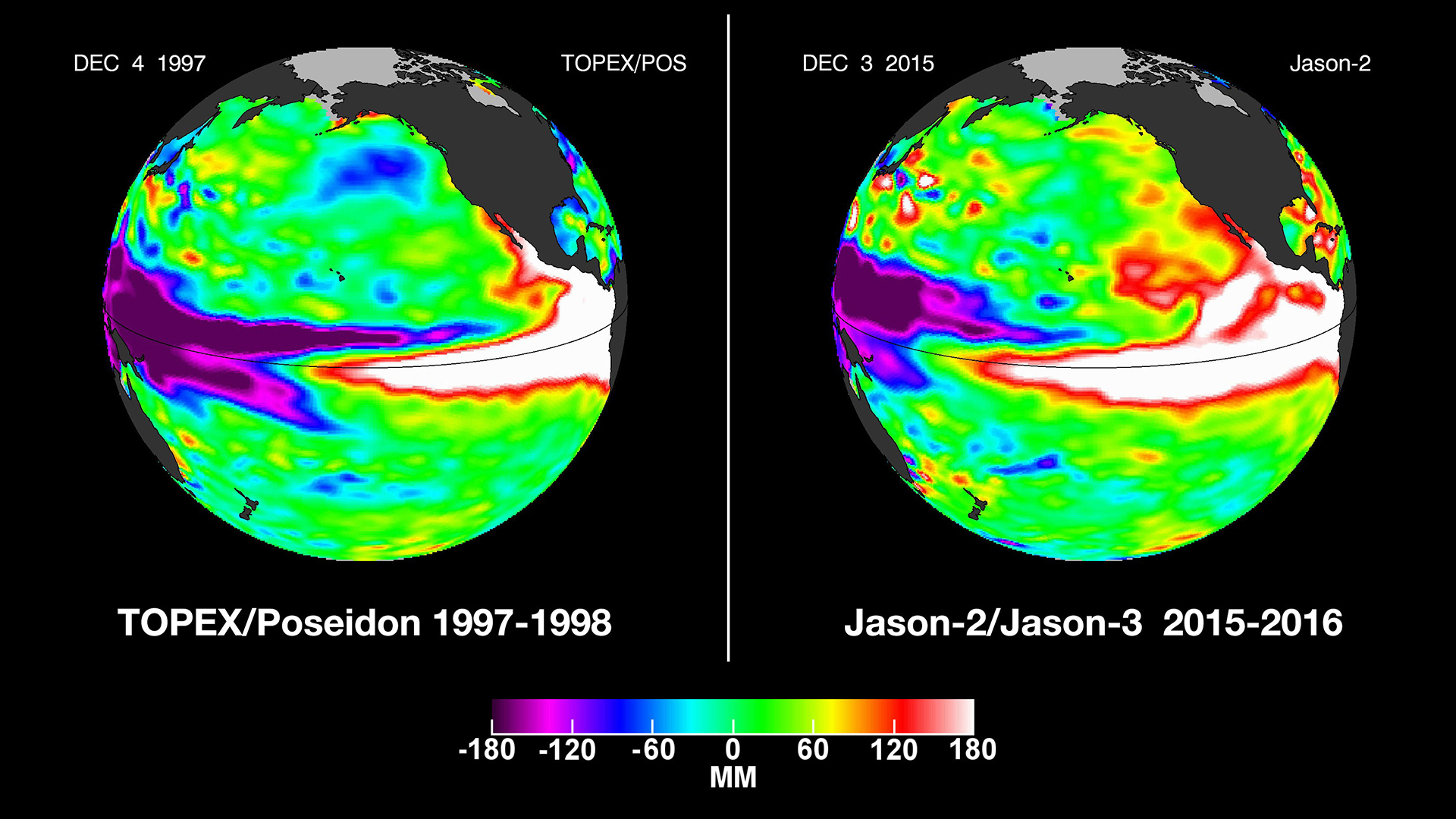

The last El Niño event occurred between February and August 2019, but its impacts were relatively weak. One of the strongest in recent decades was the El Niño that developed in the winter of 1997 to 1998. It resulted in thousands of deaths and injuries from severe storms, heatwaves, floods, fires and drought. In the US, devastating storms in the south damaged infrastructure and crops, while the north experienced above-normal temperatures and very little rain and snowfall.

Between July 2020 and March 2023, a rare triple-dip La Niña upended weather patterns around the world. The three-year event was partly responsible for record-breaking rain and severe flooding in Australia, a record-breaking Atlantic hurricane season in 2020 and the third most active hurricane season in 2021.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Aimee Gabay is an independent journalist based in London, U.K. Focusing on land rights, nature and climate change, her reporting has appeared in Al Jazeera, Mongabay and New Scientist.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus