Odds of 'strong' El Niño now over 95%, with ocean temperatures to 'substantially exceed' last big warming event

Sizzling ocean temperatures in the east-central tropical Pacific throughout July indicate there is a good chance El Niño conditions will remain strong for the next six months.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

This year's El Niño may drive ocean temperatures to "substantially exceed" those recorded during the last strong event in early 2016, scientists have warned.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA) latest El Niño update also says there is a more than 95% chance the event will last through to February 2024, with far-reaching climate impacts.

"El Niño is anticipated to continue through the Northern Hemisphere winter," NOAA staff wrote in the update. "Our global climate models are predicting that the warmer-than-average Pacific ocean conditions will not only last through the winter, but continue to increase."

Scientists officially announced the onset of El Niño in early June. El Niño is an ocean-warming event that typically occurs every two to seven years in the central and eastern Pacific, driving air temperatures up around the globe.

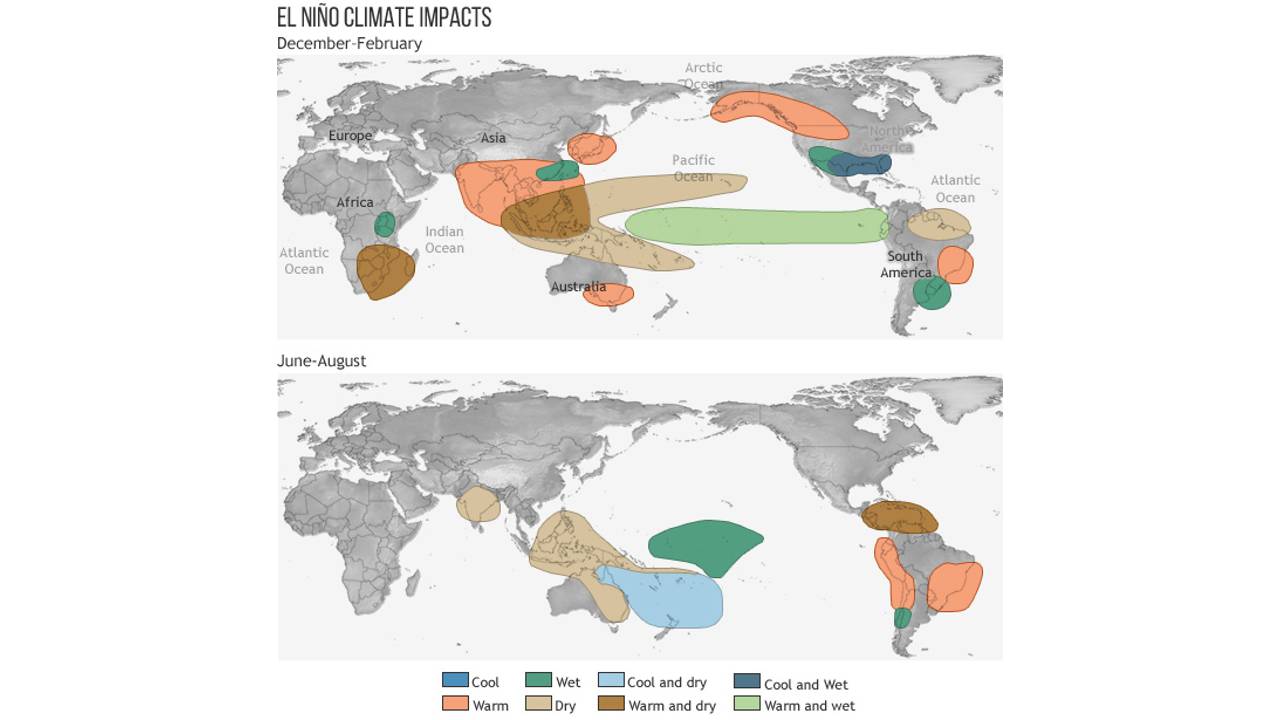

Its strongest climate impacts are usually felt during the Northern Hemisphere's winter and early spring, bringing more rain and storms across the southern U.S., southeastern South America, the Horn of Africa and eastern Asia. In other parts of the world, such as southeastern Africa and Indonesia, El Niño leads to drier conditions and may increase the risk of drought.

Related: Florida waters now 'bona fide bathtub conditions' as heat dome engulfs state

To track El Niño's progress, scientists measured sea surface temperatures in the east-central tropical Pacific Ocean. Abnormally high temperatures seem to confirm early predictions that this year's event could be a big one. Atmospheric conditions are also consistent with a long-lasting El Niño, according to NOAA.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"El Niño is a coupled phenomenon, meaning the changes we see in the ocean surface temperatures must be matched by changes in the atmospheric patterns above the tropical Pacific," the update said. More rain and clouds over the central Pacific, as well as weak pressure in the east and reduced trade wind activity in the west, suggest "the system is engaged and that these conditions will last through the winter," staff added.

Sea surface temperatures in the east-central tropical Pacific exceeded the long-term average for 1991 to 2020 by 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit (1 degree Celsius) throughout the month of July. Temperatures from May to July — a three-month average called the Oceanic Niño Index — were also 1.4 F (0.8 C) higher than usual and marked the second warmer-than-average Oceanic Niño Index in a row.

"We need to see five consecutive three-month averages above this threshold before these periods will be considered a historical 'El Niño episode,'" the update said. "Two is a good start."

There is "a good chance" the Oceanic Niño Index will match or exceed the threshold for a "strong" El Niño, the update added.

And forecasters are now confident the event will remain strong through to next year, although this doesn't necessarily equate to strong impacts locally, they noted

El Niño affects global weather patterns, as well as the Atlantic and Pacific hurricane seasons. The event usually dampens hurricanes over the Atlantic Ocean, but this year's sizzling water temperatures could mitigate this dampening effect , according to NOAA's Climate Prediction Center.

While a hurricane update in May predicted a 30% chance of higher activity over the Atlantic, the latest forecast said there is a 60% chance of an "above normal season," with up to 21 named storms and five major hurricanes.

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus