La Niña is dead — what that means for this year's hurricanes and weather

Scientists thought La Niña was coming. It didn't — at least for now. What could that mean for this year's hurricane season, and how might long-term climate change affect El Niño and La Niña patterns?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

After one of the strongest El Niños on record ended in 2024, meteorologists predicted La Niña — the counterpart to this climate pattern — would follow. Signals of a slowly developing and "unusual" La Niña strengthened over the winter, but began to falter in recent months. By March it was dead.

So what happened — and how might that impact this summer's weather and the coming Atlantic hurricane season?

What is ENSO?

El Niño is a seasonal shift in Pacific Ocean temperatures that can suppress hurricanes, change rainfall patterns and bend the jet stream. Its cold-water counterpart, La Niña, tends to do the opposite: feed Atlantic hurricanes and elevate wildfire risk in the West. Together, they form the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO).

ENSO refers to seasonal climate shifts rooted in Pacific Ocean surface temperature changes. Changes in wind patterns and currents can draw cold water from the deep ocean, where it interacts with the atmosphere in complex ways. Even small deviations in sea surface temperatures can tilt global weather over the coming months toward hot and dry — or rainy and cool — depending on the region.

"It's an incredibly powerful system," said Emily Becker, a University of Miami research professor and co-author of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA) ENSO blog. "El Niño and La Niña conditions affect rainfall, snow, temperature, the hurricane season, and tornado formation. They've been tied to fluctuations in the financial markets, crop yields, and all kinds of things.”

"Scientifically, we care about it because it's really cool," she told Live Science. "But practically, we care because it gives us this early idea about the next six to 12 months."

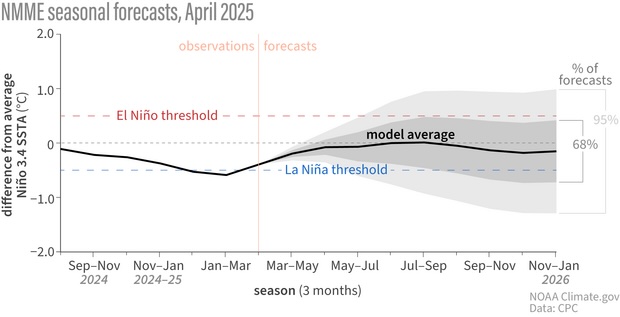

Scientists monitor a narrow strip in the Pacific Ocean near the equator. A 0.9-degree-Fahrenheit (0.5-degree Celsius) rise or fall in average surface temperature there, sustained for five overlapping three-month periods, can signal the onset of El Niño or La Niña, respectively.

However, the "average" is a moving target, based on a 30-year baseline, from 1991 to 2020, which is becoming outdated as the climate warms. "We're always playing catch-up," Tom Di Liberto, a former NOAA meteorologist and ENSO blog contributor, told Live Science.

ENSO-neutral patterns occur when surface temperatures hover near the long-term norm. But neutral doesn't mean benign — it may just mean the forecast is trickier.

Why was La Niña so short-lived?

Instead of asking why La Niña was short-lived, the better question might be whether it happened at all.

While ocean surface temperatures this winter dipped below average, they didn't stay that way long enough: By mid-April, NOAA forecasters revealed that a full-fledged La Niña event had failed to develop.

Why not?

"Trade winds play a big role," Muhammad Azhar Ehsan, a climate scientist at Columbia Climate School's Center for Climate Systems Research, told Live Science. He explained that weakening trade winds in the eastern Pacific likely kept cold water from rising to the surface — a key step in forming a robust La Niña.

But the story may not be over. When the 30-year temperature baseline is revised to include more recent, warmer years, future analysts might reclassify this winter's La Niña in the historical record, even if it didn't qualify in real time.

What does ENSO-neutral mean for the weather?

Without El Niño or La Niña tipping the scale, forecasting gets harder. These patterns sharpen the blur of seasonal predictions, adding crucial information about how the weather might drift from the usual script. Without them, when ENSO is neutral, they're left squinting into the future with little more than historical averages and climate trends.

"Without an El Niño or a La Niña, a range of other factors drive seasonal weather," James Done, a project scientist at the NSF National Center for Atmospheric Research, told Live Science. "These are less well understood, and the strength of the relationships is weaker. It's very complex."

Still, forecasters generally agree that this summer will likely be hotter than normal. "Surprise, surprise," Done said, "we have a background warming trend."

What does ENSO-neutral mean for the Atlantic hurricane season?

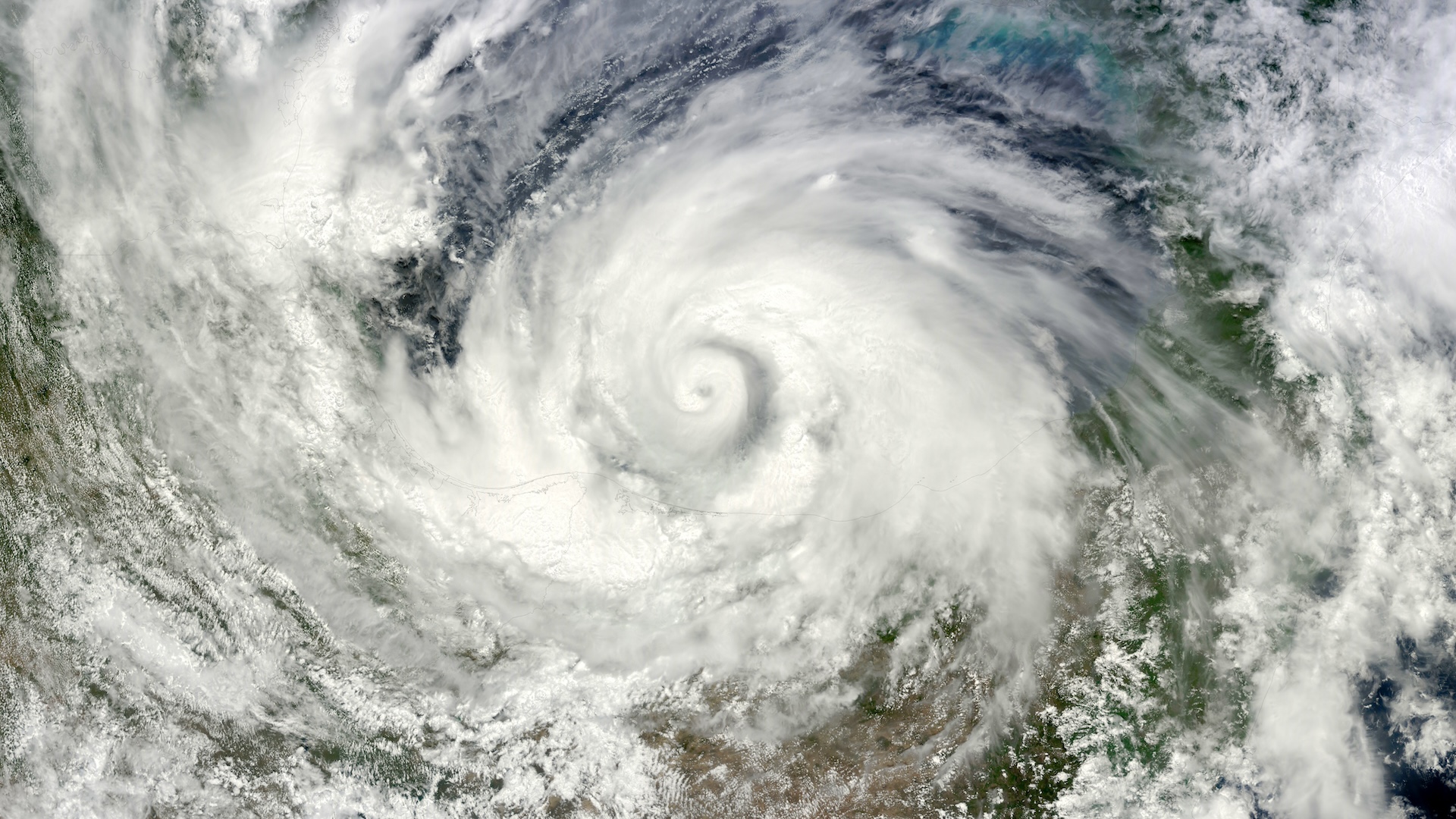

El Niño usually suppresses hurricanes, whereas La Niña and neutral conditions let them run wild. With a warm Atlantic and ENSO expected to stay neutral, that could mean a busy season.

"El Niño tends to increase vertical wind shear, and vertical wind shear tears apart hurricanes," Phil Klotzbach, a research scientist and hurricane forecast expert at Colorado State University, told Live Science via email. "Consequently, [without El Niño], we anticipate relatively hurricane-favorable wind shear patterns this summer and fall."

Others offered optimism. Ehsan said a cooling trend in the Atlantic from February to March could signal a quieter Atlantic hurricane season.

However, scientists say old rules of thumb become less reliable as background conditions change. "Last year was a weird one," Di Liberto said, referring to La Niña. "All signs pointed toward a horrible hurricane season, but it wasn't the worst-case scenario it could have been."

2023 didn't follow the script either. "We had an El Niño in 2023 but still saw more storms than usual," Done said. "So, there's a big debate: Does El Niño still kill off hurricanes, or are oceans now so warm that it changes the relationship? It's an open question."

When will the next El Niño or La Niña hit?

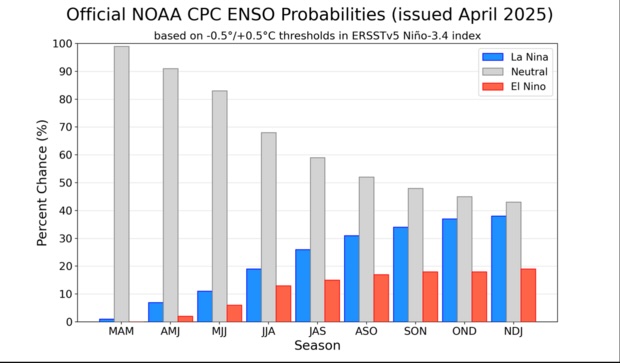

In an April 10 statement, NOAA representatives wrote that El Niño or La Niña conditions likely won't turn up this summer and that ENSO-neutral conditions are expected to last through October.

As summer fades to fall and winter, the chances for La Niña rise, but the most likely scenario is still ENSO-neutral.

That said, scientists caution against putting too much stock into springtime ENSO forecasts. "Spring is a messy time for forecasting," Di Liberto said. That's because ENSO conditions primarily form during winter and fade into the spring, offering fewer reliable signals. "June is usually when things get more confident," he added.

How will climate change impact ENSO patterns?

No one knows how climate change will affect ENSO patterns, but scientists are concerned about the warming oceans and atmosphere.

"Warmer air holds more water. It's fundamental," Becker said. "That's a factor in why we're seeing some hurricanes deposit unbelievable amounts of rain — it's partly due to the higher moisture capacity of the atmosphere."

Warm waters can extend a hurricane season or fuel storms farther north. Once envisioned as coastal threats, storms are increasingly driving inland. For example, Hurricane Helene devastated Appalachian communities hundreds of miles from the sea in 2024. "You're making a better and bigger sponge, and it gets wrung out somewhere," Di Liberto said. "And communities have to deal with incomprehensible amounts of rainfall and flooding."

However, our understanding of hurricanes is incomplete, Done said. Our observational record extends back less than 160 years — just a blink of geologic time. Scientists who have studied the geologic record of ancient cyclones have found evidence of stronger hurricanes making landfall in the distant past, often tied to periods of climate change.

If the present is the key to the past, the past nods back: Earth has seen worse — and with oceans warming fast, scientists warn it may only be a matter of time before historically unprecedented storms strike again.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Evan Howell is a Colorado-based science journalist, contributing to Live Science with a focus on Earth science. His work has appeared in Science, Scientific American, Eos Magazine, and other outlets. Evan holds a bachelor’s degree from Appalachian State University and a master’s in Geology from Northern Arizona University. Before journalism, he spent over a decade working as a Senior Geologist.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus