Sex prediction: Am I having a boy or girl?

How ultrasound offers sex prediction for your unborn baby.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

There are many methods of sex prediction out there for expecting parents, but the most commonly used and widely accepted is ultrasound.

Ultrasound exams have a variety of purposes during pregnancy, but the use that often receives the most attention is its ability to reveal the sex of the baby.

Some parents-to-be can't wait to find out whether they're having a boy or a girl, while others choose to put off knowing the sex until birth. Either way, a sonogram — the grainy, black-and-white image that results from an ultrasound scan — will be the baby's earliest picture and a couple's first chance to see the developing fetus.

Ultrasound uses high-frequency sound waves to produce an image on a screen of the baby in the mother's uterus. The scans are typically done at least twice during pregnancy, but the one done between 18 and 22 weeks is when the sonographer (ultrasound technician) might identify the sex of the baby, if parents want to know, according to the U.S Food & Drug Administration.

Expectant parents who want their child's sex to remain a secret until birth are in the minority, said Dr. Stephen Carr, director of the Prenatal Diagnosis Center and of maternal-fetal medicine diagnostic imaging at Women & Infants Hospital of Rhode Island in Providence. He said about 85% of couples want to find out the baby's sex before delivery. They do so for several reasons: to know how to paint the nursery, pick a name or satisfy their curiosities about the family composition.

Yasmine S. Ali is an award-winning physician writer who has published across multiple genres and media. She is President of LastSky Writing, LLC, and has 25 years of experience in medical writing, editing, and reviewing, across a broad range of health topics and medical conditions.

Dr. Ali is board certified in general internal medicine and the subspecialty of cardiovascular disease. She is a Fellow of the American College of Cardiology (FACC) and a Fellow of the American College of Physicians (FACP).

However, "more and more people are telling us they want to wait until the baby arrives to find out the sex," Carr said. "It's the last great surprise left," he noted.

Increasingly, Carr said, couples have asked him to write down the baby's sex and place the answer in a sealed envelope. This is because some parents-to-be want to host a gender-reveal party for family and friends to share the news.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Beyond ending the guessing game, there are can be medical reasons why mothers and fathers may want to learn the sex of their baby from an ultrasound, such as identifying some congenital conditions which are more prevalent in one sex.

U.S. hospitals have used ultrasound since the late 1970s and early '80s, Carr said. But the common prenatal scan wasn't intended as an exam to find out the baby's gender; it was meant to image the developing fetus for other medical reasons, he said.

Although the test can be done at any point during pregnancy, women typically get their first one during the first trimester. This early ultrasound is often done to confirm a pregnancy, detect the fetal heartbeat and determine the due date, according to the Mayo Clinic.

A second ultrasound is usually done between the 18th and 22nd weeks of pregnancy to make sure that the baby is growing and developing properly. It's typically during the second ultrasound that parents can learn the sex of the baby.

The scan is also done to see if a woman is having more than one baby, as well as to determine the location of the placenta and umbilical cord. In addition, ultrasound can identify certain birth defects, such as Down syndrome and spinal abnormalities, and investigate pregnancy complications, including miscarriage, according to the Mayo Clinic.

Is ultrasound a safe way to predict gender?

Ultrasound is a safe prenatal test, according to research published in the journal Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. It uses sound energy and not radiation, such as X-rays, to generate images of the fetus.

During a transabdominal ultrasound, a pregnant woman lies on her back while a clear gel is spread on her belly, according to Johns Hopkins Medicine. Next, a gel that can help transmit sound waves is placed on the skin of the abdomen, and a probe called a transducer is moved over the gel. This transmits sound waves that can produce images of the fetus as it develops inside the mother's womb.

There is no harm to the baby during the procedure, Carr said. And the only risks to the mother may come from lying flat on her back, which might make her feel dizzy, along with the discomfort of having a full bladder, he said. (Women may be asked to drink several glasses of water before an ultrasound because a filled bladder helps give clearer images.)

How accurate is gender prediction using ultrasound?

Gender predictions made by ultrasound have an accuracy rate "north of 90 percent," Carr said. But mistakes can be made when determining gender because it depends on the clarity of the images and the skills of the person interpreting them.

Until the 14th week of pregnancy, baby boys and girls look exactly the same on ultrasound, Carr said. Beyond this point, noticeable anatomical differences in the genitalia can show up on the scan.

After 18 weeks of pregnancy and beyond, Carr said that ultrasound has pretty good reliability for gender prediction if the baby is in a good position in the mother's uterus (meaning that it is not in a breech, or feet-down position), and the legs are far enough apart that there is good visibility between them.

"Gender-telling is not exotic," Carr said. When a sonographer looks between the legs, if it's "an outie," it's a boy, he explained.

Be wary of keepsake ultrasounds

Carr said that he understands the psychology of expectant parents wanting to see an image of their baby. However, he doesn't endorse so-called "bonding scans," which are also known as recreational or keepsake ultrasounds. These scans are done to produce keepsake pictures or videos, and not for medical reasons.

Ultrasound should be used as a diagnostic tool when there's a medical reason to do one, Carr said. The procedure is tightly regulated when it occurs in a hospital or medical clinic, he added.

That's generally not the case for commercial places doing keepsake images: There is no regulation of ultrasound facilities outside of a medical setting, so their quality can vary wildly, Carr said. And the technicians may have limited medical training to interpret the scans, he noted.

Non-invasive Prenatal Testing (NIPT)

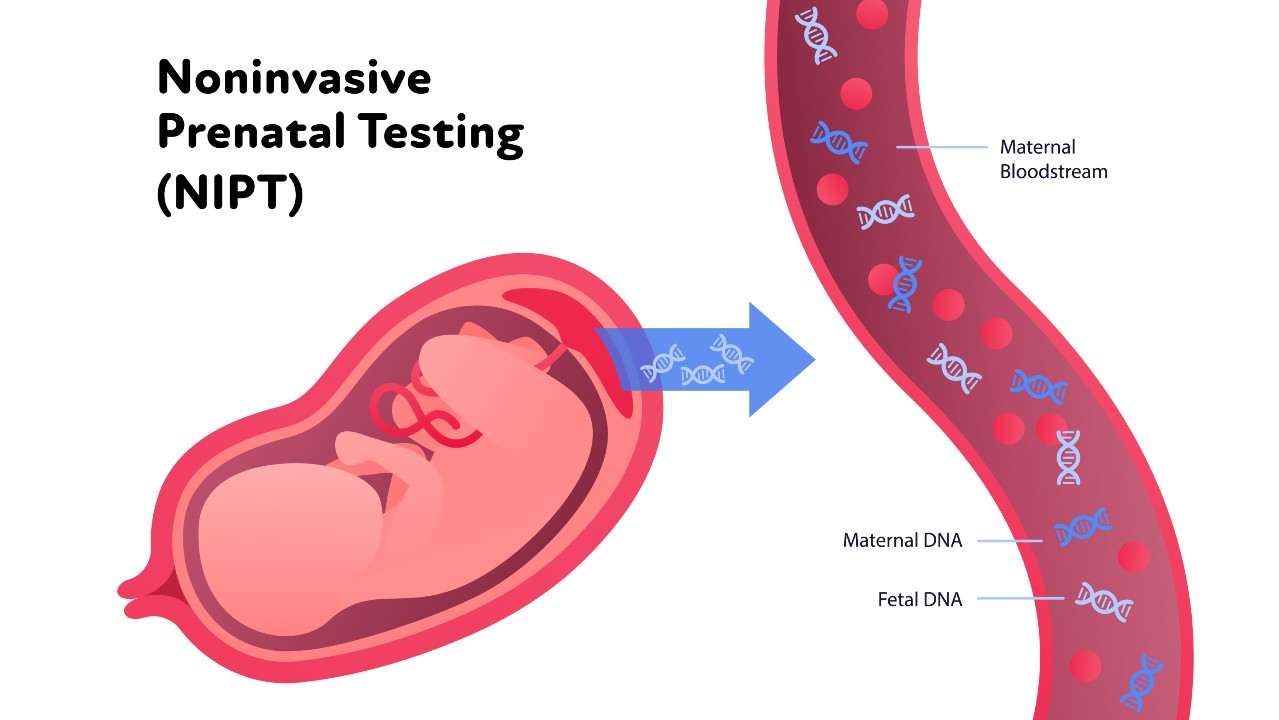

A type of screening called Non-invasive Prenatal Testing (NIPT) is used by doctors during pregnancy to screen for genetic conditions such as Down Syndrome and Edwards Syndrome (syndromes whereby children are born with 3 copies of a chromosome instead of 2), according to the NHS. The test examines a fragment of DNA that’s released from the mother’s placenta into the bloodstream and contains the genetic information of the fetus. A simple blood test from the mother is able to collect the DNA required to carry out NIPT.

Along with detecting genetic conditions, the NIPT test can reveal the sex of the fetus after only the 7th gestational week, according to the Norwegian Institute of Public Health. There are now at-home NIPT kits, such as SneakPeek, which use a small blood sample – taken from the fingertip – to identify the presence of Y chromosomes (only found in males).

Old wives' tales are fun but generally not reliable for predicting sex

For some people, waiting until the 18th week of pregnancy to find out the sex of a baby can feel like an eternity. To fill the void, people may turn to some of the following six old wives' tales to predict whether the fetus is a boy or girl.

Baby bump: One popular belief is that if a woman is carrying the baby high, she is supposedly having a girl, while carrying the baby low means it's a boy. "Carrying high or low is a function of the mother's abdominal wall muscle tone and the baby's position," Carr said. "It has no influence on gender," he said.

Food cravings: Another theory holds that a mother's food cravings during pregnancy may reveal the baby's sex, with sweet cravings signifying a girl and cravings for salty, sour or odd foods linked with a boy. "This has no basis in physiology," Carr said.

Fetal heart rate: There may be some truth to the idea that fetal heart rate could be a clue. Early in pregnancy, there is no difference in heart rate between the sexes, Carr said. But by the third trimester, a girl's heartbeat tends to be a little faster and a boy's a little slower, he said. Still, Carr cautioned that although researchers may find this association holds true over an average of 1,000 babies studied, an individual baby boy could still have a faster heartbeat, and an individual baby girl could have a slower one.

Morning sickness: Folk wisdom has linked experiencing severe morning sickness with having a girl, and this idea may have some science to back it up. Women carrying girls have higher levels of the pregnancy hormone hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin), and these higher levels are associated with an increased risk of severe morning sickness, Carr said. But he warned there's not a hard and fast relationship between morning sickness and fetal sex.

The Drano test: For this urban legend, a woman combines some of her first morning urine with the liquid drain cleaner. If the color turns green, the baby is said to be a girl; if it's blue, a boy may be on the way. Unfortunately, "there's nothing to this idea, and Drano is really caustic," Carr pointed out.

Ring test: To try this old favorite, a woman ties her wedding band to a string and hangs it over her pregnant belly to guess the baby's gender. If the ring swings back and forth, the baby is believed to be a boy. If it swings in a circle, the child is thought to be a girl. "It's fun, but it isn't science," Carr said, chuckling.

Additional resources

For a complete guide to your baby’s development check out DK’s "Pregnancy Day by Day: An Illustrated Daily Countdown to Motherhood, from Conception to Childbirth and Beyond." A great reference guide to all things related to pregnancy "The Pregnancy Encyclopedia" by DK. Johns Hopkins Medicine also explains: What Is a Fetal Ultrasound?

Bibliography

Sebastián Manzanares et al, “Accuracy of fetal sex determination on ultrasound examination in the first trimester of pregnancy,” Clinical Ultrasound, Volume 44, June 2016, https://doi.org/10.1002/jcu.22320

Ricardo Savirón-Cornudella et al, "Ultrasound measurement learning of fetal sex during the first trimester: does the experience matter?" Research and Reports in Focused Ultrasound, Volume 3, August 2015, https://doi.org/10.2147/RRFU.S88738

Maria-Elisabeth et al, "Discordant fetal sex on NIPT and ultrasound," Prenatal Diagnosis, volume 40, March 3, https://doi.org/10.1002/pd.5676

U.S. Food & Drug Administration, "Ultrasound Imaging," September 2020.

Mollie Minear et al, "Global perspectives on clinical adoption of NIPT," Prenatal Diagnosis, Volume 35, June 2015, https://doi.org/10.1002/pd.4637

Cari Nierenberg has been writing about health and wellness topics for online news outlets and print publications for more than two decades. Her work has been published by Live Science, The Washington Post, WebMD, Scientific American, among others. She has a Bachelor of Science degree in nutrition from Cornell University and a Master of Science degree in Nutrition and Communication from Boston University.

- Yasmine S. Ali, MDMD, MSCI, FACC, FACP

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus