'Missing Link' of Elephant Family Unearthed

A 27-million-year-old fossil could be the “missing link” between modern elephants and their ancestors, scientists have concluded.

Researchers led by Jeheskel Shoshani of the University of Amara in Eritrea recently discovered the lower part of a mandible in the northeast African country of Eritrea. The unearthed tooth had a structure intermediate in shape between modern and ancient elephants.

“This is really pointing toward the Horn of Africa as being a real hot bed for the evolution of elephants,” said study team member William Sanders of the Museum of Paleontology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

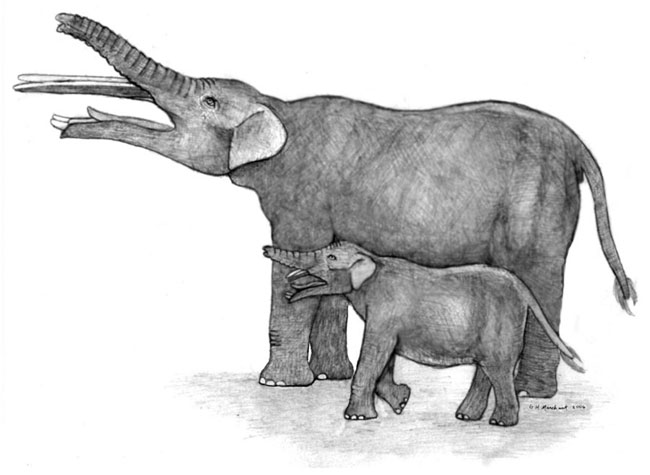

The new species, named Eritreum melakeghebrekristosi, is estimated to have been 1,067 pounds heavy and about 4.2 feet tall at the shoulder. This is far smaller than modern elephants, the researchers note this week in the online edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Elephant tree

The Asian and African elephants are the only living members of the order Probiscideans, a group of mammals that includes elephants and their extinct relatives. About 24 million years ago, the Proboscideans branched into two groups: Elephantida, which includes elephants and mammoths, and Mammutida, or the mastodons.

However, until this recent unearthing and a few others around the Horn of Africa, there were no Proboscidean fossils known for the period 25 to 28 million years ago.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

As members of the Elephantida evolved, they got larger and developed more complex features, such as advanced molars for grinding food.

Advanced teeth

The find is the oldest known fossil featuring the so-called horizontal tooth displacement found in modern elephants. Unlike humans and most other mammals, which develop baby teeth and then replace them with a permanent set of teeth, modern elephants rotate teeth five times in their lives. Their teeth don’t emerge vertically from the gums, but push toward the front of the mouth horizontally, one by one, like a conveyer belt.

New teeth grow in the back of the elephant’s mouth, and then push forward, where they wear down and eventually fall out. The quick turnover allows an elephant to get by with only four teeth, one located in each quadrant of its mouth.

“This is one adaptation for extending life and being large,” Sanders told LiveScience.

The two molar teeth had complex textures, providing more surface area for grinding and extracting precious nutrients from grassy food.

- All About Animals

- Top 10 Missing Links

- Images: The World’s Biggest Beasts

- Top 10 Deadliest Animals

- All About Evolution

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.