Derecho Facts, Formation and Forecasting

A derecho is an impressively far-reaching windstorm that is associated with a large, fast-moving line of thunderstorms.

Derecho (pronounced deh-REY-cho) means "straight" in Spanish and as its name suggests, this type of storm packs powerful straight-line winds, in contrast to the spinning winds of a tornado.

While there's no set definition of a derecho, the original term was meant to describe a storm as damaging as a tornado, said Greg Carbin, the warning coordination meteorologist at the National Oceanic at Atmospheric Administration's Storm Prediction Center. "A derecho is a special set of circumstances where thunderstorms organize and persist over a large area and produce destructive winds," Carbin said.

To qualify as a derecho, wind gusts throughout the storm must be at least 58 mph (93 kph), but particularly strong storms have had wind speeds exceeding 100 mph (160 kph). The storm also must cause wind damage across an area at least 240 miles (400 kilometers) wide to count as a derecho.

Derechos are associated with bow echoes, or bow-shaped bands of severe thunderstorms. Barreling across the landscape at speeds typically 50 mph (80 kph) or greater, the gust front of a derecho is often marked by an ominous-looking arcus cloud, also called a shelf cloud.

The winds are generated by downbursts, which are concentrated areas of strong winds produced by convective downdrafts, or cold air accelerating down toward the ground. During a derecho, individual downbursts cluster together over lengths up to 60 miles (100 kilometers).

The majority of derecho events are very well-handled by forecasters, Carbin said. Before derechos strikes, forecasters may issue outlooks, watches or warnings for high winds, severe weather and thunderstorms. The hurdle is deciding whether or not the atmosphere will organize into a derecho event. "The patterns are relatively well understood. The problem is those patterns are also fraught with failure mode," he said. The failure mode is where everything looks to be in place to support significant and life-threating weather, but it never develops, Carbin explained.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, meteorologists still don't fully understand all the subtle environmental factors that need to coalesce in order for a derecho to form. For instance, the June 29, 2012 derecho that traveled from the Midwest to the East Coast started from a single tiny thunderstorm, Carbin said. "So much comes down to these details that we really don't understand," he said.

In the United States, derechos are most common in the late spring and summer and there are typically one to three events each year in the central United States.

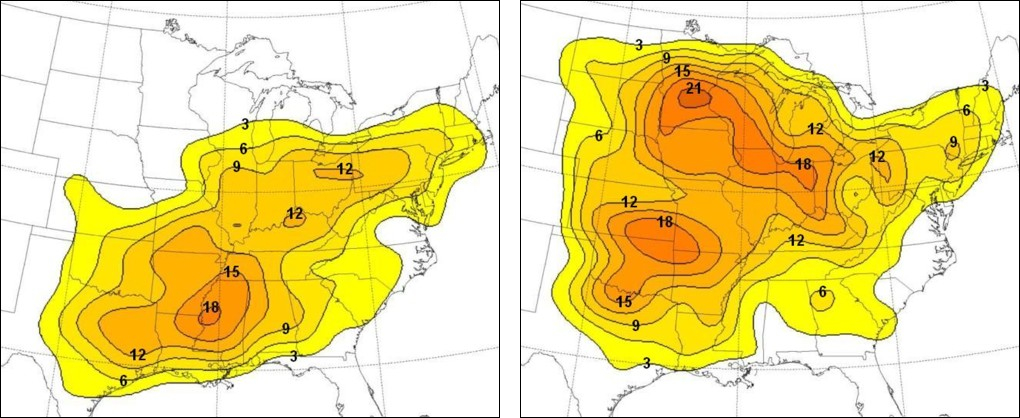

The destructive winds are most frequent in the Midwest, primarily across the Mississippi Valley, the Great Lakes and the Ohio Valley, Carbin said. One of the requirements for a derecho is a tremendous amount of energy in the form of atmospheric instability. This pattern often develops in the upper Midwest in summer, when heat waves collide with cold air blowing east from the Rocky Mountains.

The storms can be highly destructive. The June 29, 2012, derecho traveled an astonishing 450 miles (724 km) in six hours from the Midwest to the East Coast. Along the way it left millions without power and 22 dead.

A particularly severe storm on May 8, 2009, earned a new classification, super derecho, as it carved a path of destruction 100 miles (62 km) wide in Kansas. It spawned 18 tornadoes and hopped the Mississippi River into Illinois with 90- to 100-mph (145- to 160-kph) wind gusts.

Additional reporting by Megan Gannon, Live Science News Editor.

Follow Becky Oskin @beckyoskin. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Additional resources

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus