How Flies Walk on Ceilings

Walking upside-down requires a careful balance of adhesion and weight, and specialized trekking tools to combat the constant tug of gravity.

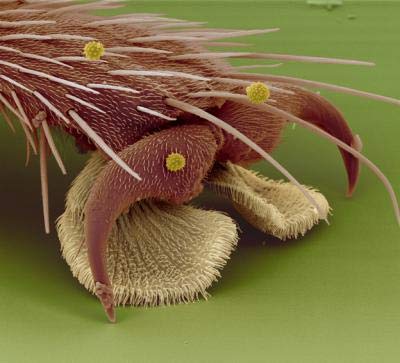

Each fly foot has two fat footpads that give the insect plenty of surface area with which to cling. The adhesive pads on the feet, called pulvilli, come equipped with tiny hairs that have spatula-like tips. These hairs are called setae.

Scientists once thought that the curved shape of the hairs suggested that flies used them to grip onto the ceiling. In fact, the hairs produce a glue-like substance made of sugars and oils.

Sticky proof

A research team from the German Max Planck Institute for Metals Research recently studied more than 300 species of wall-climbing insects and watched them all leave behind sticky footprints.

- How Viruses Invade Us

- How We Smell

- Why We Lie

- Why Ants Rule the World

- The Science of Traffic Jams

- Why Rice Krispies Go Snap, Crackle, Pop!

- The Shocking Truth Behind Static Electricity

- Why the Ground is Brown

- Why Frogs are Green

- How Dolphins Spin, and Why

"There are over one million insect species," team leader Stanislav Gorb told LiveScience. "We suppose that all of them have the secretion, but it is difficult to be 100 percent sure."

Gorb presented the findings at the Annual Meeting of the Society for Experimental Biology in April.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Flies need sticky feet to walk on ceilings, but not so sticky that they get stuck upside down. So each foot comes with a pair of claws that help hoist the gooey foot off the wall.

Flies use several different techniques to get unstuck: pushing, twisting, and peeling its footpads free.

"Methods involving peeling are always the best, because they require less energy to break the contact," Gorb said.

The combination of the feet hairs' rounded tips, the oily fluid, and a four-feet-on-the-floor rule help the inverted insect take steps in the right direction.

Lessons for robofly

Following in the fly's footsteps, robots are on their way to climbing walls.

Gorb's research team worked with a robotics group from Case Western Reserve University to design robotic feet that mimic a fly's footing.

On the bottom of the feet of a 3-ounce robot that's all legs, scientists tacked on a sticky, furry manmade material that resembles the hairy surface of a fly foot. The researchers also taught the robot how to gently peel its foot off a glass wall, just like a demure insect.

"It's the first time a robot has climbed glass in a way that was inspired by an animal," said mechanical engineer Roger Quinn.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus